Expanded power over pain is a significant result that may usefully be embraced by all human beings who experience pain – which describes just about everyone at some time or another. Acute pain communicates an urgent need for intervention; chronic pain is demoralizing and potentially life changing. Intervention required!

People who do not experience standard amounts of pain are at risk of hurting themselves. Dr. James Cox, senior lecturer at the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research at University College London, notes, “Pain is an essential warning system to protect you from damaging and life-threatening events” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat2019)). Admittedly not experiencing pain is a rare and concerning condition from which few of us suffer. Hence the practical approach considered here for the rest of humanity.

I changed my relationship to pain by working on the relationship. The result is that less pain occurs in my life and the pain that I do experience does not dominate my life. If one is completely pain-free, one is probably dead, which has different issues.

The following behaviors made a difference. Regular exercise, healthy diet, spiritual discipline (I have trained extensively in Tai Chi, but Yoga and/or meditation encompass the same results), consultations with professionals of one’s choice including medical doctors; and, here is the wild card, the purpose of this post: education in the different types of pain, including but not limited to acute pain versus chronic pain. The reader may say, “Holy cow! That’s too much work!” However, if the reader is in enough pain, then consider the possibility. What’s the alternative? Continue to suffer? Medically assisted suicide (where legal)? Opioids? The latter in particular have a place in hospice (end of life scenarios), in the week after surgery, but otherwise they are a deal with the devil. And, in any deal with the devil, be sure to read the fine print. “At a time when about 130 American die daily from opioid overdoses, scientists and drug companies are actively pursuing alternative non-opioid medications for acute and chronic pain” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat 2019)).

An example will be useful. I changed my relationship to pain, following my MDs guidance, by taking a double dose of NSAIDs – non steroidal anti-inflammatory “pain killers”. The idea is to “kill” the pain without killing the patient. This is no joke because NSAIDs such as Aleve can damage the mucous membranes of the gastro intestinal track (e.g., stomach), leading to ulcer-like conditions and the accompanying risks (not detailed here), which is why, even though they are over-the-counter, consultation with a medical doctor is important.

Doing Tai Chi changed my relationship to pain. Your mileage may vary, but I started to see results after ten weeks of dedicated daily work. My Tai Chi training has continued with one lengthy interruption for six years. My experience was the practice moved the pain threshold up. That is, I did not experience pain as acutely and when I did experience pain, it did not bother me as much. This can be a double-edged consideration. For example, the Tai Chi exercise of “holding the ball” is a stress position. One really needs a picture to see what this is.

One stands there with one’s arms encompassing a large ball at about the level of one’s chest with one’s hips tucked slightly as if sitting back. One’s whole body is engaged and conditioned. After about ten minutes one starts to heat up and after about fifteen minutes one starts to sweat. This is Tai Chi, not Yoga, but Mircea Eliade discusses similar stress positions that generate Shamanic Heat (Eliade, (1964), Shamanism, translated Willard Trask. Princeton University Press (Bollingen)).

Now a word of caution regarding the pain threshold. I went for a dermatological treatment and I got burned, literally, (fortunately, not too seriously), because I did not say “Stop – it hurts!” Granted that most people want to experience less pain, it is important to not extinguish pain completely, because pain in its acute presentation is trying to tell one something – in this case, injury to one’s skin due to heat.

Here is another example. A colleague has an inflamed ankle. It throbs. It hurts. It is not fractured but imaging shows it is enflamed, stressed out. The thing is that this is not just the person’s sprained ankle – it is his whole life. Since he needs to lose weight, he needs to get exercise. Because he cannot get sufficient exercise, he cannot lose weight. The extra weight contributes to the ankle continuing to be stressed. Double-bind! Rock and the hard place. How is this individual going to break out of this tight loop? Now I know this is going to sound crazy, but here it is: Follow doctor’s orders! Go to the physical therapy! If you have got to wear “the boot” for a couple of weeks, do so. Start low (with the number of repetitions of exercises) – go slow. If the person had access to a swimming pool, that would be ideal, but that might not be workable for many people. SPA-like treatments, soaks in Epsom salts in sensory deprivation pods have value.

Many parallel examples can be cited in which a person knows exactly what she has to do (don’t even worry about the doctor) – why is the person not doing it? Many reasons exist, but one of them is that suffering becomes a comfort zone. Suffering is sticky. “Yes, I am miserable,” the individual says, but it is a familiar misery. Suffering has become an uncomfortable comfort zone. What would it take to give that up? Once one realizes, “This is what crazy looks like,” it becomes easier to give up the suffering. This is not a deep dive into the psychology of the unconscious, yet this is not merely a physical challenge. Yes, the ankle hurts – objectively, there is even an image that shows inflammation, albeit hazy and faint. However, even if there weren’t evidence of an injury – and soft tissue damage often escapes imaging, the emotional issue – ambivalence about one’s body image (“weight”) – gets entangled with the person’s whole life. In this case, a struggle with unhealthy excess weight – and the person’s emotions run with the ball – elaborate the injury psychologically. This is also a form of catastrophizing or awfulizing (made famous by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)), but CBT did not invent it.

I gave the example of an inflamed ankle, but it might also apply to lower back pain, headaches, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which are notoriously difficult to diagnose medically. Speaking personally, I want a quick fix. We all do. However, after a while, if the “fix” does not occur, there is no in principle limit on the amount of time and effort one can spend trying to find a quick fix. After a certain time, one gets a sense that one might put the time and effort into incremental progress – finding whatever moves the dial – whatever shifts the stuckness. Here’s what I did not want to hear: This is gonna take some work. After a time, one decides to roll up the sleeves and do the hard work need to get one’s power back. Healthy diet and a well-defined exercise program are important components. Finding an MD and/or health care provider including physical therapist where the interpersonal chemistry works is on the critical path to dialing down the suffering. Here “interpersonal chemistry” is another description for empathy. Look for someone whose empathy is open enough to encompass one’s pain and suffering without being coopted by it. This is the critical path to recovery.

The distinction between acute pain and chronic pain needs to be better understood by the average citizen. An excerpt from Neurology 101 may be useful. In acute pain, the peripheral nervous system in the body’s appendages such as one’s toes reports via neural connections to the central nervous system (e.g., the brain in one’s head). The impact of a heavy object such as a large brick with my toe releases neurotransmitters at the nociceptors (we are not talking Greek and “nocio” means “pain”). The mechanics are such that a message is delivered from the periphery to the center that what is in effect a boundary violation – an injury – has occurred. The brain then tells the toe to hurt – “Ouch!” The message is delivered seamlessly to the conscious person to whom the toe “belongs” in the neural map that associates the body with conscious experience unfolding in the person’s awareness. The toe which had quietly been doing its job in helping the person walk, balance, be mobile now makes a lot of “noise” – it starts throbbing. This is what acute pain feels like.

With chronic pain the scenario gets complicated. If the injury is subjected to other stressors, slow to heal, reinjured, or otherwise neglected, then the pain may continue across a period of days or weeks and become habitual. In effect, the pain signal becomes a bad habit. The pain takes on a life of its own. What does that even mean? What starts out as a way of reminding the person to attend to the injury gets stuck on “repeat”. Like the marketing company that keeps sending your notices even after you specify “Do not solicit!” The messaging is not just from the toe to the brain, from the periphery to the center, but it gets reversed. The messaging is from the center to the periphery, from the brain to the body part. The brain tells the periphery to hurt. Chronic pain becomes a source of suffering. Here “suffering” expands to include worry that anticipates and/or expects pain, which gets further reinforced when the pain actually shows up.

The poster child for chronic pain is phantom limb pain. Not all pains are created equal. Phantom limb pain provides compelling evidence that pain is “in one’s head” only in the sense that pain is in the brain and the brain is in one’s head. Only in that limited sense is pain in one’s head. Yet the pain is not imaginary. Documented as early as the American Civil War by Silas Weir Mitchell, individuals who had undergone amputation, felt the nonexistent, missing limb to itch or cramp or hurt. The individuals experienced the nonexistent tendons and muscles of the missing limb as cramping and even awakening the person from the most profound sleep due to pain (As noted, further in Haider Warraich. (2023). The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain. New York: Basic Books, pp. 110 – 111).

Fast forward to modern times and Ron Melzack’s gate control theory of pain marshals such phantom limb pain as compelling evidence that the nervous system contains a map of the body and the body’s pains point, which map has not yet been updated to reflect the absence of the lost limb. In effect, the brain is telling the individual that his limb is hurting using an obsolete map of the body – the memory of pain. Thus, the pain is in one’s head, but not in the sense that the pain is unreal or merely imaginary. The pain is real – as real as the brain that is indeed in one’s head and signaling (“telling”) one that one is in pain. (R. Melzack, (1974), The Puzzle of Pain. Basic Books.)

Whatever the level of pain, stress is probably going to make it feel worse. Therefore, stress reduction methods such as meditation, Tai Chi, Yoga, time spent soaking in a sensory deprivation pod, and SPA-like stress reduction methods are going to be beneficial in moving the pain dial downward.

One question that has not even occurred to scientists is whether it is possible to have the functional equivalent of phantom limb pain, even though the person still has the limb functionally attached to the body. This sounds counter-intuitive, but think about it. If there is a map of the body’s pain points in the central nervous system (the brain), there is nothing that says “phantom” pains cannot occur even if an appendage still exists. For example, the high school football player who needs the football scholarship to go to college because he is weak academically; he is not good at baseball, but actually hates football. He incurs a soft tissue sports injury, which gets elaborated due to emotional conflict about his ambivalent relationship with football, leaving him on crutches for far-too-long and both physically and symbolically unable to move forward in his life. As if the only three life choices are football, baseball, and academics?! Note that the description of the injury “painful soft tissue” already opens and shuts approaches to treatment. That is the devilish thing – what is the actual and accurate description? Thus, due to the inherent delays in neuroplasticity – the update to the brain’s map of the body is not instantaneous and one does not have new experiences with a nonexistent limb – pain takes on a life of its own.

Though an oversimplification, the messaging between the peripheral and central nervous systems is reversed. Instead of the peripheral limb telling the brain of a “hurt,” the brain develops a “bad habit” of signaling pain and tells the limb to hurt. That is the experience of chronic pain – pain has a life of its own – pain becomes the dis-ease (literally), not the symptom. What then is the treatment, doctor? Physical therapy (PT) – exercises to strengthen the knee and, in effect, teach him to walk again.

Chronic pain is discouraging, demoralizing, fatiguing, exhausting, negatively impacting one’s mental status. I have been cagey about my own experience of pain in this post, but it is a matter of record that I have osteoarthritis, a progressive deterioration of the cartilage in joints such as occurs in people who are getting older and who are long term runners. The person understandably and properly continuously asks himself – what am I experiencing? And does it include pain? No one is saying the “cure” is don’t think about it (pain), don’t worry about it. No one is saying “play hurt”? “Playing hurt” is a bad idea for so many reasons, including one is going to make a bad injury worse. Professional athletes who “play hurt” may indeed get a bunch of money, but they also often dramatically shorten their careers – and that costs them money.

While distraction from one’s pain can be useful in the short term, it is not a sustainable solution. Rather when, after medical determination of the sources of pain are determined to be unable to be completely extinguished or eliminated, one is saying undertake an inquiry into what one is really experiencing. Rather than react to the uncomfortable twinges and twitches, bumps and thumps, prodding and pokes, that one encounters, ask what one is really feeling. Undertake an inquiry into what one is experiencing. If, upon consideration, the answer is “The pain is acute going from 4 to 8 to 9 on the 10 point scale,” then stop and call for backup, including taking pain killers such as NSAIDS as recommended by an MD.

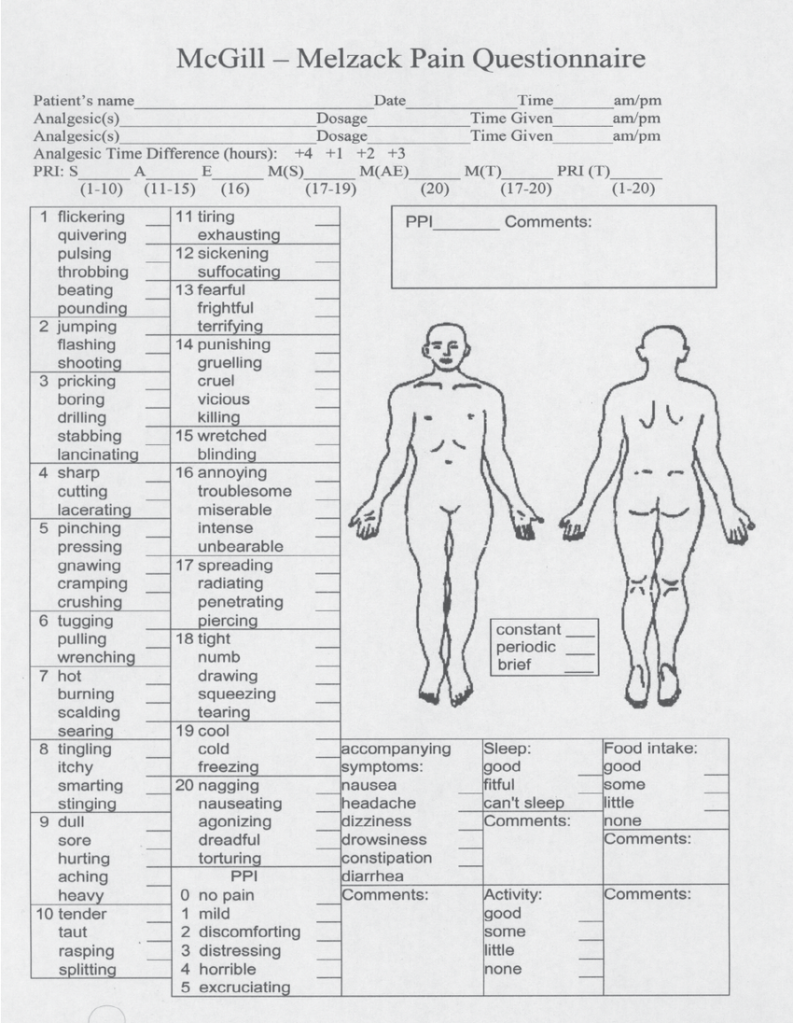

Here the vocabulary of pain is relevant. See Melzack’s McGill pain chart. [List the vocabulary]

Further background information will be useful. Haider Warraich, MD, in The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain (Basic Books, 2023) radicalizes the issue of pain that takes on a life of its own before suggesting a solution. After providing a short history of opium and morphine and opioids, culminating “in the most prestigious medical school on earth, from the best teachers and physicians, we [medical students] were unknowingly taught meticulously designed lies” (p. 185), that is, prescribe opioids for chronic pain. The reader wonders, where do we go from here? To be sure opioids have a role in hospice care and the week after surgery, but one thing is for certain, the way forward does not consist in prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

After reviewing numerous approaches to integrated pain management extending from cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to valium, cannabis and Ketamine – and calling out hypnosis (hypnotherapy) as a greatly undervalued approach (no external chemicals are required, but the issue of susceptibility to hypnotic suggestibility is fraught) – Dr Warraich recovers from his own life changing back injury in a truly “physician heal thyself” moment thanks to dedicated PT, physical therapy (p. 238). If this seems stunningly anti-climactic, it is boring enough to have the ring of truth earned in the college of hard knocks, but it is a personal solution (and I do so like a happy ending!), not the resolution of the double bind in which the entire medical profession finds itself (pp. 188 – 189). The way forward for the community as a whole requires a different, though modest, proposal. The patient signs up for and completes physical therapy (PT), a custom set of exercises tailed to his pain condition and mobility issues.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “The body is the best picture of the soul.” The default since René Descartes is to distinguish physical pain from psychic pain – what used to be called the difference between “body” and “soul” before science “proved” that the soul did not exist. (Once again, we are talking Greek “psyche” is the Greek word for “souI.”) Nevertheless, in spite of the “proof” that the soul does not exist, soul-like phenomena keep showing up. For example, if the person’s “soul” is regularly subjected to negative verbal feedback from those in authority, the person becomes physically ill – ulcers, headaches, lower back pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). As noted, these are notoriously difficult to diagnoses. The adverse childhood experience survey (ACE) provides solid evidence that psychic and moral injuries correlate significantly with major medical disorders (e.g., Felitti 2002).

One big issue is that we (science and scientists) lack a coherent, effective account of emergent properties. One with neurons. The alternative is the current reductive paradigm according to which, in spite of contrary assertions, on has trouble explaining that things really are what they seem to be – that table are tables andmade of microscopic components such as atoms. We start with neurons. We are neurons “all the way down.” Neurons generate stimuli; stimuli generate sensations/experiences; experiences generate [are] responses; responses form patterns; patterns generate meaning; meaning generates language. With the emergence of language, things really start to get interesting. Organized life reaches “take off” speed. Language generates community; community generates – or rather is functionally equivalent to – culture, art, poetry, science, technology, and the world as we know it.

What about individuals who are put in a double-bind by circumstances as when someone in authority makes a seemingly impossible demand? For example, the army Sargent gives what seems to be a valid military order to the corporeal to shoot at the rapidly approaching auto, thinking it is a suicide car bomb, but it is really an innocent family. The soldier, thinking the order is valid and that he is protecting his team, follows the order. The solider is now both a perpetrator and a survivor. People have gotten hurt who ought not to have been hurt. Moral inquiry. Moral trauma has occurred. Tai Chi is not going to save this guy. This take the form of guilt – which is aggression – hostile feeling and anger – turned against one self. The individual’s agency – the individual’s power as an agent to choose – is compromised by contingent circumstance, including the individual’s unavoidable choice in the circumstance, since taking no action is also a choice.

This is why the ancient Greeks invented tragedy. A careful reading of the Greek tragedies, which cannot be adequately canvassed here, shows that virtually every tragic hero has the compromised agency characteristic of a double bind. Oedipus is a powerful agent, yet compromised and brought low by inadequate information. Information asymmetries! Antigone’s agency is bound, doubly, by the conflict between the imperatives of politics and the integrity of family. Agamemnon’s agency is compromised by the negative aspect of honor and pride and an overweening narcissism. Iphigenia’s agency is compromised by literally being bound and gagged (admittedly a limit case). Double-binds have also been hypothesized to contribute to the causation of major mental illness (Bateson 1956). Contradictory messages from parents, explicit versus implicit, spoken versus unspoken, are particularly challenging. Here the fan out to related issues is substantial.

I changed my relationship to pain and suffering by reading all thirty existing Greek tragedies. One might say if something is worth doing, it is worth over-doing, and the reader might try starting with just one. Examples of pain and suffering occur in abundance: acute pain – Hercules puts on the poisoned cloak, which burns his flesh; chronic pain – Philoctetes has a wound that will not heal and throbs periodically with painful sensations; and suffering – Oedipus is misinformed about who is his birth mother and after having children with her he suffers so from his awareness of his violation of family standards that he mutilates himself, tearing his eyes out. The latter would, of course, be acute pain, but the cause, the trigger, is thinking about what he has done in relation to the expectations of the community, namely, violating the incest taboo.

Now, according to Aristotle, the representation of such catastrophes is supposed to evoke pity and fear in the audience (viewer) of the classic theatrical spectacle. Indeed, such spectacles – even though the violence usually happens “off stage” and is reported – are not for the faint of heart. We seem to want to identify with the characters in a narrative, which, in turn, activates our openness to their experiences in an entry level empathy that communicates a vicarious experience of the character’s struggle and suffering. Advanced empathy also gets engaged in the form of appreciation of who is the character as a possibility in relation to which the viewer (audience) considers what is possible in her of his own life. One takes a walk in the other’s shoes, after having taken off one’s own. Other examples of similar experiences include why (some) people like to see horror movies. One does not run screaming from the theatre, but conventionally appreciates that the experience is a vicarious one – an “as if” or pretend experience. Likewise, with “tear jerker” style movies – one gets a “good cry,” which has the effect of an emotional purging or cleansing.

Now I am not a natural empath, and I have had to work at expanding my empathy. In contrast, the natural empath is predisposed, whether by biology or upbringing (or both), to take on the pain and suffering of the world. Not surprisingly this results in compassion fatigue and burn out. The person distances him- or herself from others and displays aspects of hard-heartedness, whereas they are actually kind and generous but unable to access these “better angles.” It should be noted that empathy opens one up to positive emotions, too – joy and high spirits and gratitude and satisfaction – but, predictably, the negative ones get a lot of attention.

“Suffering” is the kind of thing where what one thinks and feels does make a difference. Now no one is saying that Oedipus should have been casual about his transgressions – “blown it off” (so to speak); and the enactment does have a dramatic point – Oedipus finally begins to “see” into his blind spot as he loses his sight. Really it would be hard to know what to say. Still, the voice of reality would council alternatives – other ways are available of making amends – making reparations – perhaps more than two “Our Fathers” and two “Hail Marys” as penance – what about community service or fasting? “Suffering” is not just a conversation one has with oneself about future expectations. It is also a conversation one has with oneself about one’s own inadequacies and deficiencies (whether one is inadequate or not). For example, unkind words from another are hurtful. In such cases what kind of “pain” is the hurt? We get a clue from the process of trying to manage such a hurt. The process consists in setting boundaries, setting limits, not taking the words personally (even though inevitably we do). The hurt lives in language and so does the response. Therefore, in an alternative scenario, one takes the bad language in and turns it against oneself. One anticipates a negative outcome. One gets guilt (once again, regardless of whether one has does something wrong or not).

The coaching? If you are suffering from compassion fatigue, then dial down the compassion. This does not mean become hard-hearted or mean. Far from it. This means do not confuse a vicarious experience of pain and suffering with jumping head over heels into the trauma itself. What may usefully be appreciated is that practices such as empathy, compassion, altruism are not “on off” switches. They are not all or nothing. Skilled executioners of these practices are able to expand and contract their application to suit the circumstances. To be sure, that takes practice. The result is expanded power over vicariously shared pain and suffering. One gets power back and is able to assist the other in recovering their power too. (Further tips and techniques on how to change one’s thinking and expand one’s empathy are available in my Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide (with 24 full color illustrations by Alex Zonis), also available as an ebook.)

Before concluding, I remind the reader that “all the usual disclaimers.” This is a personal reflection. The only data is my own experience and bibliographical references that I found thought provoking. “Your mileage may vary.” If you are in pain (which, at another level and for many spiritual people, is one definition of the human condition) or if you are in the market for professional advice, start with your family doctor. If you do not have one, get one. Talk to a spiritual advisor of your own choice. Above all, “Don’t hurt yourself!” This is not to say that I am not a professional. I am. My PhD is in philosophy (UChicago) with a dissertation entitle Empathy and Interpretation. I have spent over 10K hours researching and working on empathy and how it makes a difference. So if you require expanded empathy, it makes sense to talk to me. A conversation for possibility about empathy can shift one’s relationship with pain.

Bibliography

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J., 1956, Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, Vol. 1, 251–264.

Corley, Jacquelyn. (2019). The Case of a Woman Who Feels Almost No Pain Leads Scientists to a New Gene Mutation. Scientific American. March 30, 2019. Reprinted with permission from STAT. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-case-of-a-woman-who-feels-almost-no-pain-leads-scientists-to-a-new-gene-mutation/

Eliade, Mircea. (1964). Shamanism. Princeton University Press (Bollingen).

Felitti VJ. (2002). The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead. The Permanente Journal (Perm J). 2002 Winter;6(1):44-47. doi: 10.7812/TPP/02.994. PMID: 30313011; PMCID: PMC6220625.

Melzack, R. (1974). The Puzzle of Pain. New York: Basic Books.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project