Home » empathic receptivity

Category Archives: empathic receptivity

The empathic dozen: Top 12 empathy lessons

Listen to this post as a podcast on Spotify –

(0) The one-minute empathy training. Drive out aggression, hostility, bullying, prejudice of all kinds, dignity violations, hypocrisy, making excuses, finger pointing, cynicism, resignation, bad language, manipulation, injuries to self-esteem, competing to be the biggest victim, and politics in the pejorative sense of the term, and empathy naturally comes forth. Most people are naturally empathic and, if given half a chance, they will spontaneously and willingly speak and act empathically. The training can be spoken in one minute. However, actually implementing it is going to take some work. Start here:

(1) Are you willing? Perform a readiness assessment: The first step of a readiness assessment is one must be willing. If one has the willingness, then the hard work begins of listening, taking the Other’s perspective, giving up being right and righteous, giving up being aggrieved, making requests, asking for what one needs. As soon as one announces a commitment (for example): “I am going to expand empathy in my life,” then all the reasons that it is utterly impossible to do so show up. “What are you thinkin’ fella?” Not enough time. Not enough money. Not enough empathy!

Resistance to empathy does not mean that one fails the readiness assessment to expand one’s empathy. It means that one is a human being. The fact that a person is looking at this blog post is itself a positive sign that one is ready. Do not set the bar too high (at least at the start); but recognize that it is going to take something extra to expand one’s empathy. People have blind spots about empathy. People have blind spots, period.

The work needed to overcome these blind spots results in “a rigorous and critical empathy.” Therefore, note that throughout this blog post when the term “empathy” is used it is as an abbreviation for “a rigorous and critical empathy.”

When it comes to doing the work required actually to listen and respond empathically to Others, people make exceptions for themselves. A person fails the readiness test for empathy without work up front to clean up the person’s own inauthenticities. The tough thing is that the inauthenticities are not limited just to empathy. Being willing to clean up one’s authenticities is precisely the empathy lesson. This is different than taking the easy way out—this can be “empathy the hard way.” The readiness for empathy requires doing the hard work required to create a clearing for empathic success, a clearing of integrity and authenticity. This leads immediately to the next recommendation.

(2) Establish and maintain firm boundaries between the self and Other in relating empathically, but practice being inclusive: Empathy is all about boundaries. Empathy is all about moving across the boundary between self and Other. The boundary is not a wall, but a semi-permeable membrane that allows communication of feelings, thoughts, intentions, and so on. As noted above, the poet Robert Frost asserts that good fences make good neighbors. But fences are not walls. Fences have gates in them. Over the gate is inscribed the word “empathy,” which invites visits across the boundary.

Some of the most empathic people that I know are also the strongest and most assertive regarding respect for boundaries. Being empathic does not mean being a push over. You wouldn’t want to mess with them. Where such people show up, empathy lives; and shame, cynicism, and bullying have no place. In what is one of the defining parables of Christian community (that of the Parable of the Good Samaritan), empathy is what enables the Samaritan to be open to a vicarious experience of what the survivor of the assault is experiencing; and then it is the Samaritan’s compassion and ethics that tell him what to do about it. The two are distinct. Empathy tells us what the Other experiencing; compassion (and our good moral upbringing) tell(s) us what to do about it. Yet empathy expands the boundary of who is one’s neighbor to be more-and-more inclusive, extending especially to those whose humanity has been put at risk by misfortune. Be inclusive.

(3) Empathy deescalates anger and rage: When people do not get the empathy to which they feel entitled, they start to suffocate emotionally. They thrash about emotionally. Then they get enraged. The response? De-escalate rage by explicitly acknowledging the break down—“It seems you really have not been treated well.” Clean up the misunderstanding, and restore the empathic relatedness. Empathy does many things well. One of the best is that empathy deescalates anger and rage.

Without empathy, people lose the feeling of being alive. They tend to “act out”—misbehave—in an attempt to regain the feeling of vitality that they have lost. Absent an empathic environment, people lose the feeling that life has meaning. When people lose the feelings of meaning, vitality, aliveness, dignity, their emotions become unbalanced. When the emotions become unbalanced, their behavior does so too and goes “off the rails.” Sometime pain and suffering seem better than emptiness and meaninglessness—but not by much. People then can behave in self-defeating ways in a misguided attempt to awaken a sense of aliveness and regain emotional balance.

This is a re-description of bullying, which requires a word of caution. One should never underestimate the power of empathy. Never, Yet affective empathy does not work with bullying in so far as being empathic leaves the person who provides the empathy vulnerable. The bully (and a small set of disturbed individuals with anti-social personality disorder) will take one’s vulnerability and use it the would-be empathizer. Instead the recommendation (as in (2) above) is to set limits, establish boundaries, speak truth to power (in so far as bullying is an abuse of power), and defend one’s integrity. What does work in the face of bullying is “top down,” cognitive empathy. Think like one’s opponent. Take a walk in the Other’s shoes in order to reestablish the possibility of conflict resolution, de-escalation, and, if push comes to shove, mounting an effective defense. (On “thinking like one’s opponent in war and peace and business, see Zenko (2015) in the references below.)

“Empathy is oxygen for the soul” is a metaphor. But a telling one. When people do not get empathy—and a short list of related things such as dignity, common courtesy, respect, fairness, humanity—they feel that they are suffocating—emotionally. People act out in self-defeating ways in order to get back a sense of emotional stability, wholeness and well-being—and, of course, acting out in self-defeating ways is self-defeating. (For further on empathy as oxygen for the soul see Kohut (1977).) One requires expanded empathy. Pause for breath, take a deep one, hold it in briefly while counting to four, exhale, listen, speak from possibility.

(4) Avoid the risk of the banality of empathy by thinking before speaking and taking action. This phrase, “the banality of empathy,” is a reference to Namwali Serpall’s (2019) “spin” on Hannah Arendt. Hannah Arendt’s lovely phrase “one trains one’s imagination to go visiting [the Other]” is an exact description of empathic understanding, though not empathic receptivity of the Other’s feelings/emotions. One does not blindly adopt the Other’s point of view—one takes off one’s own shoes before trying on the Other’s. “Enlarged thinking” takes the points of view of many Others, and is what enables people to judge by means of feelings as well as concepts. This is not loss of one’s self in projection and merger, but rather a thoughtful shifting of perspective and appreciation of what shows up as one does so. It is a false splitting to force a choice between feeling and thinking—both are required to have a complete experience of the Other.

A recurring theme in Arendt’s thinking is that evil and is a consequence of thoughtlessness. If one empathizes thoughtlessly, if one applies empathy without thinking, the banality of empathy, then the result may be unpredictable. One is not going to like the result. One is at risk of empathy misfiring as projection, emotional contagion, conformity, and so on. Just so. Do not be a sloppy thinker. A rigorous and critical empathy is required to guard against these risks, and a rigorous and critical empathy thinks before speaking and taking action.

One can always make a splash by throwing a rotten tomato, and dumping on empathy has become something of a growth industry. However, these devaluing treatments of the acknowledged strengths and limitations of empathy are directed at a strawman, a caricature of empathy, fake empathy, not the rigorous and critical empathy engaged here. For a complete detailed answer to many of these sensationalist pot boilers, see Chapter Three: Empathy and its discontents of my Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature (Palgrave Macmillan 2025 (and you should have the college, university or local library order a copy (as it is an academic book and they have budget for these types of works)).

(4) Avoid the risk of the banality of empathy by thinking before speaking and taking action. This phrase, “the banality of empathy,” is a reference to Namwali Serpall’s (2019) “spin” on Hannah Arendt. Hannah Arendt’s lovely phrase “one trains one’s imagination to go visiting [the Other]” is an exact description of empathic understanding, though not empathic receptivity of the Other’s feelings/emotions. One does not blindly adopt the Other’s point of view—one takes off one’s own shoes before trying on the Other’s. “Enlarged thinking” takes the points of view of many Others, and is what enables people to judge by means of feelings as well as concepts. This is not loss of one’s self in projection and merger, but rather a thoughtful shifting of perspective and appreciation of what shows up as one does so. It is a false splitting to force a choice between feeling and thinking—both are required to have a complete experience of the Other.

A recurring theme in Arendt’s thinking is that evil and is a consequence of thoughtlessness. If one empathizes thoughtlessly, if one applies empathy without thinking, the banality of empathy, then the result may be unpredictable. One is not going to like the result. One is at risk of empathy misfiring as projection, emotional contagion, conformity, and so on. Just so. Do not be a sloppy thinker. A rigorous and critical empathy is required to guard against these risks, and a rigorous and critical empathy thinks before speaking and taking action.

One can always make a splash by throwing a rotten tomato, and dumping on empathy has become something of a growth industry. However, these devaluing treatments of the acknowledged strengths and limitations of empathy are directed at a strawman, a caricature of empathy, not the rigorous and critical empathy engaged here. For a complete detailed answer to many of these sensationalist pot boilers, see Chapter Three: Empathy and its discontents of my Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature (Palgrave Macmillan 2025 (and you should have the college, university or local library order a copy (as it is an academic book and they have budget for these types of works)).

(5) Empathy is a method of data gathering about the other person: Simply stated, empathic receptivity is a technique of data collection about the experiences of other people. This is not mental telepathy. Human beings are receptive to one another, open to one another experientially, but with some conditions and qualifications. You have to listen to the other person and talk with him or her. You have to interact with the person. The one individual gets a sample of the experience of the other individual. The one individual gets a trace of the other individual’s experience (like in data sampling) without merging with the Other.

Through its four phases, empathy is a method of gathering data about the experience of the person as the other individual experiences what the individual is experiencing. This data (starting with (1) vicarious experience) is processed by (2) empathic understanding of possibilities and (3) empathic interpretation of perspectives in order to give back to the other person his or her own experience by means of (4) empathic responsiveness in language or gesture in such a way that the other person recognizes the experience as the person’s own.

The neurological basis of this empathic receptivity may be mirror neurons or another associative network of neurons that function to support an affective (emotional) resonance that higher mammals share with one another. Even if mirror neurons were to turn out to be a myth, the disclosive truth would still be that human beings are all related. We resonate together and must exert effort not to do so.

This approach to empathy (empathy as a method of data gathering) goes a long way towards solving the problems of compassion fatigue and burnout among nurses, teachers, doctors, care-takers, first responders, clergy, and so on. As noted, in empathy, if one is listening to another person and that person is suffering, then, strange as it may sound, one should suffer—but not too much. One suffers only a little bit, one suffers vicariously. The empathizer is open to the suffering of the other person but only as a sample of the suffering, a trace affect. This is a vicarious experience, not a shared experience, which would provide the full, overwhelming weight of the suffering.

If one is experiencing compassion fatigue, then one may have made one of the most common empathy mix ups of confusing “empathy” with “compassion.” The language provides a clue. The complaint is not “empathy fatigue.” The complaint is “compassion fatigue.” The recommendation is to turn down one’s compassion and tune up one’s empathy.

Now, as noted repeatedly, the world needs both more compassion and expanded empathy; but what is perhaps needed the most is a working balance between the two. One needs to increase the granularity (filtering) of one’s openness to the other person. Instead of empathically sampling one in five emotional upsets vicariously, one may try sampling one in ten, until one regains one’s own emotional equilibrium. Yes, one suffers, vicariously, but if suffering emotionally flattens one as one is giving empathy, one is doing it incorrectly. One is over-empathizing and over-identifying. One needs to regulate—in this case, “tune down”—one’s receptivity to the other person. This is easier said than done, of course, which is why empathy lessons are needed. Taking the matter of “tuning up or down” up a level, it deserves a technique of its own. Thus, the next item.

(6) Empathy is a tuner or dial, not an “on-off” switch: Engaging with the issues and sufferings with which people are struggling can leave the would-be empathizer (“empath”) vulnerable to burnout and “compassion fatigue.” As noted, the risk of compassion fatigue is a clue that empathy is distinct from compassion, and if one is suffering from compassion fatigue, then one’s would-be practice of empathy is off the rails, in breakdown. Maybe one is being too compassionate instead of practicing empathy. In empathy, the listener gets a vicarious experience of the Other’s issue or problem, including their suffering, so the listener suffers vicariously, but without being flooded and overwhelmed by the Other’s experience.

Empathy is like a dial or dimmer—tune it up or tune it down. If one is overwhelmed by suffering as one listens to the other person’s struggles and predicaments, one is doing it—practicing empathy—incorrectly, clumsily, and one needs skills training in empathy. The whole point of a vicarious experience—and training one’s vicarious experiences as distinct from merger or over-identification—is to get a sample or trace of the Other’s experience without being inundated by it. One needs to increase the granularity of one’s empathic receptivity to reduce the emotional or experiential “load.”

Empathy is also like a filter—decrease the granularity and get more of the Other’s experience or increase the granularity (i.e., close the pores) and get less. The power in distinguishing empathic receptivity from empathic understanding, interpretation, and responsiveness, is precisely so one can divide and conquer in the practice and performance of empathy lessons. Each has a characteristic breakdown, and each can be improved with practice and attention to the relevant dials that influence the process of relating.[i]

The recommendation? Listen, pause for breath to a count of four, acknowledge the pain and suffering, interpret the resistance, and continue applying conflict resolution principles—identify and express grievances, invite self-expression, elicit requests, offer suggestions, make demands, formulate interpretations, propose compromises, brain-storm alternative possibilities, commit to action items, apply the soothing salve of empathy to the narcissistic injuries of the participants, and iterate—until resolution.

(7) Decline the choice between empathy and compassion. Decline the artificial choice between expanding empathy and fighting and reducing the empire of prejudice, imperialism, the pathologies of capitalism, and violence. Some have tried to force a choice between compassion and empathy. This is a choice that must be refused. The world needs both more compassion and expanded empathy. In summary, it is not a choice between expanding empathy and ending/reducing empire, and an engagement with both is needed. Survivors of all of these boundary violations ask for empathy. When survivors are asked, “What do you want—what would make it better? What would soothe the trauma?” then rarely do they say punish the perpetrator (though occasionally they do). Mostly they ask for acknowledgement, to be heard and believed, to hear the truth about what happened, for apology, accountability, restitution, rehabilitation, prevention of further wrong (see Herman 2023).[ii] Rarely do survivors make forgiveness a goal, especially not if forgiveness would require further interaction with the perpetrator (though self-forgiveness should not be dismissed). It bears repeating: survivors ask for empathy, not an end to empire, though, once again, both expanded empathy and an end to empire are needed.

(8) Empathy is the new love: Empathy is love by other means; and love is empathy by other means. Even a distinction with as much history, tradition, and gravitas as “love,” undergoes developments and transformations. For example, you know how in high fashion gray is the new black? Well, empathy is the new love. It is what people really want—to feel heard—to be heard—to be “gotten” as the possibility they authentically know themselves to be.

People want to be gotten for who they authentically are. They want empathy. What about the old love? According to folk wisdom, love is “blind” (in this case, that would be the “old love”); and, furthermore, love is compared (by Socrates, Plato, and many others) to a state of madness. So far, the old love resembles the symptoms of tertiary, neuro-syphilis. Of course, empathy is famous for its diverse breakdowns too—as emotional contagion, conformity, projection, and mistranslation. However, when these break downs of empathy are engaged, worked through, and transformed, then the results are precisely breakthroughs in empathy, enabling satisfying relationships and the building of community. When love is “worked through,” the result is the routinization of desire, “washin’ dishes and dirty diapers,” as documented in the song “Makin’ Whoopee,” in which “Whoopee” expresses the how romantic idealization gets de-idealized in the hard work of sustaining family life.

This is not to privilege empathy or “dump on love,” since both love and empathy are essential to community, but to assess each one in its respective strengths are limitations. Empathy is what people fundamentally desire—to be gotten for who they authentically are. When one person’s desire aims at the other person’s desire, then desire begets desire. The desire of the Other’s desire is precisely the empathic moment.

(9) Empathy is multi-dimensional: Empathy is the process of grasping first-hand what the other person is experiencing because one experiences it too. This often seems to be an instantaneous process in which one just “gets it”—knows first person and first-hand what is happening with the other person. But other times the process shows up as a more extended, time-dilated one of a sustained listening, through which the other person’s life and experiences come gradually into view as empathic receptivity—a kind of vicarious experience of the person.

The person is flourishing or stuck, in possibility or upset, and one realizes that one is relating, not only to the static state in which the person finds herself, but also to the aspirations, ideals, hopes, fears—in short, to the possibilities that the person is confronting and projecting as plans and ambitions going forward into the future.

Empathic understanding is understanding of possibilities. These possibilities are not something hidden from the person; on the contrary, the person knows intimately about them; the possibilities determine who the person is presently being in living into the future; but sometimes there are indeed hidden and undeclared possibilities to which the person is deeply committed and of which the person is only marginally aware.

For example, think of the friend who had been married (and divorced) three times. He was attempting to shock me with his lack of commitment in relationships, and was surprised to hear me respond: “Well, you are really committed to marriage.” The possibility of marriage gets unpacked in an empathic interpretation such that the marriages seemed to him to be a duck, but the now former spouses thought they were a rabbit, resulting, as one says, in irreconcilable perceptions if not “irreconcilable differences.” In context, my response about his commitment seems to have been an empathic enough one that validated his experience of the value of marriage, while acknowledging his struggle, upset, and frustration. It opened up whole new possibilities for him going forward in relating to his former spouses, to the institution of marriage, and, mostly, to himself.

Thus, empathy is a roundtrip from the vicarious experience of empathic receptivity; to the grasping of possibilities in empathic understanding; to the making explicit of diverse possibilities in empathic interpretation; to empathic responsiveness, delivering over to the other person his experience in such a way that he recognizes it as his own experience.

(10) Each phase of empathy has characteristic breakdowns: Break throughs in empathy arise from working through the breakdowns of empathy. Empathic receptivity breaks down into emotional contagion, suggestibility, and being over-stimulated by the inbound communication of the other person’s strong feelings. If one stops in the analysis of empathy with the mere communication of feelings, then empathy collapses into emotional contagion.

If one takes emotional contagion—basically the communication of emotions, feelings, affects, and experiences—as input to further empathic processing, then emotional contagion (communicability of affect) makes a contribution to empathic understanding.

A vicarious experience of emotion differs from emotional contagion in that one knows that the other person is the source of the emotion. That makes all the difference. I feel anxious or sad or high spirits, because I am with another person who is having such an experience, and I “pick it up” from him. I can then process the vicarious experience, unpacking it for what is so and what is possible in the relationship. This returns empathy to the positive path of empathic understanding, making possible a breakthrough in “getting” what the other person is experiencing. Then the one person can contribute to the other person regulating and mastering the experience.

Or instead of empathic understanding grasping possibility for flourishing and relatedness, empathic understanding can break down in conformity. Humans live and flourish in possibilities; and empathic understanding breaks down as “no possibility,” “stuckness,” and the suffering of “no exit” (one definition of hell in a famous play of the same name by Sartre). One follows the crowd; one does what “one does”; one validates feelings and attitudes according to what “they say”; and, with apologies to Thoreau, lives the life of “quiet desperation” of the “modern mass of men.”

Almost inevitably, when someone is stuck, experiencing shame, guilt, upset, emotional disequilibrium, and so on, the person is fooling himself—has a blind spot—about what is possible. This does not mean that it is easy to be in the person’s situation or for the person to see what is missing. Far from it. But we live in possibilities that we allow to define our constraints and limitations—for example, see the above-cited friend who was married and divorced three times. At the risk of being simple-minded, dear friend, have you considered the alternative—cohabitation? Though this might not be a “silver bullet,” it points to a breakthrough in empathic understanding. If one acknowledges that the things that get in the way of our relatedness are the very rules we make up about our relationships and what is possible within them, then we get freedom to relate to the rules and possibilities precisely as possibilities, not absolute “shoulds.” We stop “shoulding” on ourselves.

For example, if cohabitation is considered unacceptable due to personal or community standards, then let’s have a conversation for possibility about that (and so on). This brings us to the next break down—the break down in empathic interpretation.

This is the aspect of empathy that corresponds most exactly to the folk definition of empathy—taking a walk in the other person’s shoes. But in the breakdown of empathic interpretation, one takes that walk with one’s own foot size. This is also called “projection.” One has to take off one’s own shoes before trying on the Other’s. Now that can sometimes tell you something useful, because human beings have many things in common; but most times—and especially with most of the tough cases—empathy is going to run off the path. Imaginatively elaborating the metaphor, the other person is literally flat footed, whereas I have a high arch on my foot; the other person is an amputee, a “blade runner” with a high-tech prosthesis—a different kind of “feet.” I am a “duck” and have webbed, duck feet; the other person is a “rabbit” and has furry, rabbit feet.

The recommendation? Own your projections. Take back the attributions of your own inner conflicts onto other people. One gets one’s power back along with one’s projections. Stop making up meaning about what is going on with the other person; or, since one probably cannot stop, at least distinguish the meaning—split it off, quarantine it, take distance from it, so that its influence is limited. Absent a sustained conversation with the other person, be humble that you have any idea what is going on with the other person.

Having worked through vicarious experiences, possibilities for overcoming conformity and stuckness, and taken back one’s projections, one is ready to attempt to communicate to the other person one’s sense of their experience. One is going to try to say to the other what one gets from what they told you, giving back to the other one’s sense of their experience. And what happens? Sometimes it works; but other times something gets “lost in translation.”

The breakdown of empathic response occurs within language as one fails to express oneself satisfactorily. I believed that I empathized perfectly with the other person’s struggle and effort, but (in this example) I failed completely to communicate to the other person what I got from listening to her. My empathy remains a tree in the forest that falls without anyone being there. My empathy remains silent, inarticulate, uncommunicative. I get credit for a nice empathic try (assuming that I really have tried); but the relatedness between the persons is not an empathic one. If the other person is willing, then go back to the start and iterate. Learn from one’s mistakes. Try again.

The fact that one failed does not mean that the commitment to empathy is any less strong; just that one did not succeed this time; and one needs to keep trying. It takes practice. Empathy lessons are useful. The exchange in questions was one of them. Learn from one’s mistakes.

Often understanding emerges out of misunderstanding. What I say is clumsy and creates a misunderstanding (in a given context). But when the misunderstanding is clarified and cleaned up, then empathy occurs. Thus, break throughs in empathy emerge out of breakdowns. So whenever a breakdown in empathy shows up, do not be discouraged; rather be glad, for a break through is near.

(11) Train and develop empathy by overcoming the obstacles to empathy: People want to know: Can empathy be taught? People complain and authentically struggle: I just don’t get it—or have it. In spite of the substantial affirmative evidence that empathy can be taught, is being taught (e.g., see NYU Langone Health: http://www.empathyproject.com (2014/2024)), the debate continues. The short answer is: Yes, empathy can be taught.

What happens is that people are taught to suppress their empathy. People are taught to conform, follow instructions, and do as they are told. We are taught in first grade to sit in our seats and raise our hands to be called on and speak. And there is nothing wrong with that. It is good and useful at the time. No one is saying, “Leap up and run around yelling” (unless it is summer vacation!). But compliance and conformity are trending; and arguably the pendulum has swung too far from the empathy required for communities to work effectively for everyone, not just the elite and privileged at the top of the food chain.

Now do not misunderstand this: people are born empathic, but they are also born needing to learn manners, respect for boundaries, and toilet training. Put the mess in the designated place or the community suffers from diseases. People also need to learn how to read and do math and communicate in writing. But there is a genuine sense in which learning to conform and follow all the rules does not expand our empathy or our community. It does not help the cause of expanded empathy that rule-making and the drumbeat of compliance are growing by leaps and bounds.

If people can be taught to contract their empathy, they can be taught to expand it. That means that the gains in expanding community that are owed to compliance and conformity, for the most part, stay as they are—empathy expands. How so?

Teaching empathy consists in overcoming the obstacles to empathy that people have acquired. When the barriers are overcome, then empathy spontaneously develops, grows, comes forth, and expands. That is the training minus all the hard work.

The hard work? Remove the blocks to empathy such as dignity violations, devaluing language, gossip, shame, guilt, egocentrism, over-identification, lack of integrity, inauthenticity, hypocrisy, making excuses, finger pointing, jealousy, envy, put downs, being righteous, stress, burnout, compassion fatigue, cynicism, denial, competing to be the biggest victim, injuries to self-esteem, and narcissistic merger—and empathy spontaneously expands, develops, and blossoms. (I hasten to add, in general, there is nothing wrong with narcissistic merger; it is just not empathy.)

Formal, in-school education is generally designed to instill conformity, especially in the earlier grades, into what is hoped to be a productive, compliant corporate and industrial workforce, not instill empathy.

That is changing. Thanks to powerful programs such as Mary Gordon’s empathy initiative, “The Roots of Empathy,” but it is still too soon to predict the outcome.[i] Now I am in favor of education and learning reading, math, and writing. I am in favor of history and the humanities and the Physical Sciences too. However, the Arts and the Humanities—the disciplines that are arguably those committed to expanding empathy—are “on the ropes” due to chronic budget cuts. It is hard to connect the dots, which is what is required by the administrators, between studying literature or philosophy and high paying jobs in the global digital economy. The idea that education is an end in itself, teaching the graduate to learn to learn, and enabling the graduate to adapt to a volatile employment market, in which it is hard to predict what jobs are hot, is an enduringly valid idea, but not one with much traction. The Humanities are precisely the disciplines that include empathy lessons in narrative, literature, history, performance, and self-expression in diverse media.

Studying the Humanities and literature, art and music, rhetoric and languages, opens up areas of the brain that map directly to empathy and powerfully activate empathy. Read a novel. Write a story. Go to the art museum. Participate in theatre. These too are empathy lessons, fieldwork, and training in empathic receptivity. [iv]

Reduce or eliminate the need for having the right answer all the time. Dialing down narcissism, egocentrism, entitlement (in the narrow sense), and dialing up questioning, motivating relatedness, encouraging self-expression, inspiring inquiry and contribution, developing character, and, well, expanding empathy.

Yes, empathy can be taught, but it does not look like informational education. It looks like shifting the person’s relatedness to self and Others, developing the capacity for empathy, accessing the grain of empathy that has survived the education to conformity. Anything that gets a person in touch with her or his humanness counts as training in empathy.

(12) There is enough empathy to go around, even though it does not seem that way on most days—why is that? You know how agriculture can grow enough food to feed everyone on the planet but people are still starving, because of the use of food by politics in the negative sense to perpetrate hostility and bad actions? Enough empathy is available to go around; but it is badly distributed. People are living and working in empathy deserts. Organizational politics, stress and burnout, attempts to control and dominate, egocentrism and narcissism, out-and-out aggression and greed, all result in empathy getting hoarded locally, creating “empathy deserts” even amid an adequate supply. Therefore, this approach does not call for “more” empathy, but rather for “expanded” empathy. The difference is subtle. Saying “We need more empathy here!” implies the person is unempathic—and that is an insult, a dignity violation. In extreme cases, a person may in fact lack empathy in a formal, technical sense—the serial killer, the psychopath, and persons suffering from some particular mental illnesses (or even a case of flu). However, such persons are an exception or an exceptional situation that will pass. Well, it is the same thing with empathy. This results in the one-minute empathy training as indicated at the start of this post. Back to the top.

For further top empathy tips and techniques see the Chapter, “Conclusion: Top 40 Empathy Lessons” in Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition, Chicago: Two Pears Press, 2024.

End Notes

[i] This point is missed in the otherwise engaging and spirited public debate featured in the New York Times, still relevant after all these years, in which Jamil Zaki identifies empathy with compassion, and—how shall I put it delicately?—a conversation of deaf persons occurs between celebrity academics about the importance of listening. See Jamil Zaki, (2016), Does empathy help or hinder moral action? The New York Times, Dec. 29, 2016: http://tinyurl.com/gwmfpxp [checked on 06/26/2025]. Great minds think alike? It should be noted that, when not trying to “cap the rap” in the Times, Zaki (and Ciskara) (2015) provide a penetrating and incisive analysis of the value of “trying harder” to be empathic in the context of the kinds of empathic breakdowns under discussion in this work. My take? If one works at it, “tries harder,” one discovers that empathy expands.

[ii] Judith L. Herman, MD. (2023). Truth and Repair: How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice. New York: Basic Books.

[iii] Gordon, Mary. (2005). The Roots of Empathy: Changing the World Child by Child. New York/Toronto: The Experiment (Thomas Allen Publishers).

[iv] Madeline Levine. (2012). Teach Your Children Well: Why Values and Coping Skills Matter More than Grades, Trophies, or ‘Fat Envelopes’. New York: Harper Perennial. I acknowledge Paul Holinger, MD, for calling my attention to this one.

References

Lou Agosta. (2025). Chapter Three: Empathy and its discontents. In Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. This is a pricey academic book, but readable, so have the college, university or local library order a copy. They have budget for this kind of work.

Lou Agosta. (2024). Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

Judith L. Herman, MD. (2023). Truth and Repair: How Trauma Survivors Envision Justice. New York: Basic Books.

Heinz Kohut. (1977), The Restoration of the Self, International Universities Press.

Namwali Serpall. (2019). The banality of empathy. The New York Review: https://www.nybooks.com/online/2019/03/02/the-banality-of-empathy/[checked on June 26, 2025]

NYU Langone Health. (2014/2024). http://www.empathyproject.com

Zaki, Jamil and Mina Ciskara. (2015). Addressing empathic failures, Current Directions in Psych-ological Science, December 2015, Vol. 24, No. 6: 471–476. DOI: 10.1177/0963721415599978.

Zaki, Jamil. (2016). Does empathy help or hinder moral action, The New York Times, December 29, 2016: http://tinyurl.com/gwmfpxp [checked on 01/06/20

Zenko, Micah. (2015). Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy. New York: Basic Books.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and The Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide is now an ebook – and the universe is winking at us in approval!

The release of the ebook version of Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide coincides with a major astronomical event – a total solar eclipse that traverses North America today, Monday April 8, 2024. The gods are watching and wink at us humans to encourage expanding our empathic humanism!

My colleagues and friends are telling me, “Louis, you are sooo 20th Century – no one is reading hard copy books anymore! Electronic publishing is the way to go.” Following my own guidance about empathy, I have heard you, dear reader. The electronic versions of all three books, Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide, Empathy Lessons, and A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy – drum roll please – are now available.

A lazy person’s guide to empathy guides you in –

- Performing a readiness assessment for empathy. Cleaning up your messes one relationship at a time.

- Defining empathy as a multi-dimensional process.

- Overcoming the Big Four empathy breakdowns.

- Applying introspection as the royal road to empathy.

- Identifying natural empaths who don’t get enough empathy – and getting the empathy you need.

- The one-minute empathy training.

- Compassion fatigue: A radical proposal to overcome it.

- Listening: Hearing what the other person is saying versus your opinion of what she is saying.

- Distinguishing what happened versus what you made it mean. Applying empathy to sooth anger and rage.

- Setting boundaries: Good fences (not walls!) make good neighbors: About boundaries. How and why empathy is good for one’s well-being. Empathy and humor.

- Empathy, capitalist tool.

- Empathy: A method of data gathering.

- Empathy: A dial, not an “on-off” switch.

- Assessing your empathy therapist. Experiencing a lack of empathic responsiveness? Get some empathy consulting from Dr Lou. Make the other person your empathy trainer.

- Applying empathy in every encounter with the other person – and just being with other people without anything else added. Empathy as the new love – so what was the old love?

Okay, I’ve read enough – I want to order the ebook from the author’s page: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Advertisements

https://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.7/html/safeframe.html

REPORT THIS AD

Practicing empathy includes finding your sense of balance, especially in relating to people. In a telling analogy, you cannot get a sense of balance in learning to ride a bike simply by reading the owner’s manual. Yes, strength is required, but if you get too tense, then you apply too much force in the wrong direction and you lose your balance. You have to keep a “light touch.” You cannot force an outcome. If you are one of those individuals who seem always to be trying harder when it comes to empathy, throttle back. Hit the pause button. Take a break. However, if you are not just lazy, but downright inert and numb in one’s emotions – and in that sense, e-motionless – then be advised: it is going to take something extra to expand your empathy. Zero effort is not the right amount. One has actually to practice and take some risks. Empathy is about balance: emotional balance, interpersonal balance and community balance.

Empathy training is all about practicing balance: You have to strive in a process of trial and error and try again to find the right balance. So “lazy person’s guide” is really trying to say “laid back person’s guide.” The “laziness” is not lack of energy, but well-regulated, focused energy, applied in balanced doses. The risk is that some people – and you know who you are – will actually get stressed out trying to be lazy. Cut that out! Just let it be.

The lazy person’s guide to empathy offers a bold idea: empathy is not an “off-off” switch, but a dial or tuner. The person going through the day on “automatic pilot” needs to “tune up” or “dial up” her or his empathy to expand relatedness and communication with other people and in the community. The natural empath – or persons experiencing compassion fatigue – may usefully “tune down” their empathy. But how does one do that?

The short answer is, “set firm boundaries.” Good fences (fences, not walls!) make good neighbors; but there is gate in the fence over which is inscribed the welcoming word “Empathy.”

The longer answer is: The training and guidance provided by this book – as well as the tips and techniques along the way – are precisely methods for adjusting empathy without turning it off and becoming hard-hearted or going overboard and melting down into an ineffective, emotional puddle. Empathy can break down, misfire, go off the rails in so many ways. Only after empathy breakdowns and misfirings of empathy have been worked out and ruled out – emotional contagion, conformity, projection, superficial agreement in words getting lost in translation – only then does the empathy “have legs”. Find out how to overcome the most common empathy breakdowns and break through to expanded empathy – and enriched humanity – in satisfying, fulfilling relationships in empathy.

Order from author’s page: Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Order from author’s page: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Read a review of the 1st edition of Empathy Lessons – note the list of the Top 30 Empathy Lessons is now (2024) expanded to the Top 40 Empathy Lessons: https://tinyurl.com/yvtwy2w6

Read a review of A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/49p6du8p

Order from author’s page: A Critical Review of Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Order from author’s page: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition: https://tinyurl.com/mfb4xf4f

Above: Cover art: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition, illustration by Alex Zonis

Advertisements

https://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.7/html/safeframe.html

REPORT THIS AD

Order from author’s page: A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/mfb4xf4f

Above: Cover art: A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy, illustration by Alex Zonis

Finally, let me say a word on behalf of hard copy books – they too live and are handy to take to the beach where they can be read without the risk of sand getting into the hardware, screen glare, and your notes in the margin are easy to access. Is this a great country or what – your choice of pixels or paper!?!

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Paul Ricoeur, Philosopher of Empathy

This article on Paul Ricoeur, empathy, and the hermeneutics of suspicion in literature will be engaging to students of Ricoeur and empathy alike. One can download the PDF directly from the journal Etudes Ricœeurienne / Ricoeur Studies website: http://ricoeur.pitt.edu/ojs/ricoeur/article/view/628

The article is in English and an abstract is cited below at the bottom. If the above link does not work for any reason, then scroll to the bottom, where one can download the PDF within this blog post.

Meanwhile, I offer a recollection of my personal encounter with Professor Ricœur starting when I was a third year undergraduate at the UChicago. (This is an excerpt from a pending manuscript on empathy in the context of literature.)

By the time I was an undergraduate in my junior year in college, Paul Ricoeur had just arrived at the University of Chicago. Professor Ricoeur had attempted to play a conciliatory role in listening to and addressing student grievances in the face of entrenched method of lecturing by ex cathedra by mandarin professors at the Sorbonne, Paris, France, and related schools in the system. Though Ricoeur did not use the word “empathy” in his role as administrator at the University of Nanterre, he was attempting to play a role in conflict mediation, during the strike of student and workers in Paris in May 1968, a role in which empathy is famously on the critical path.

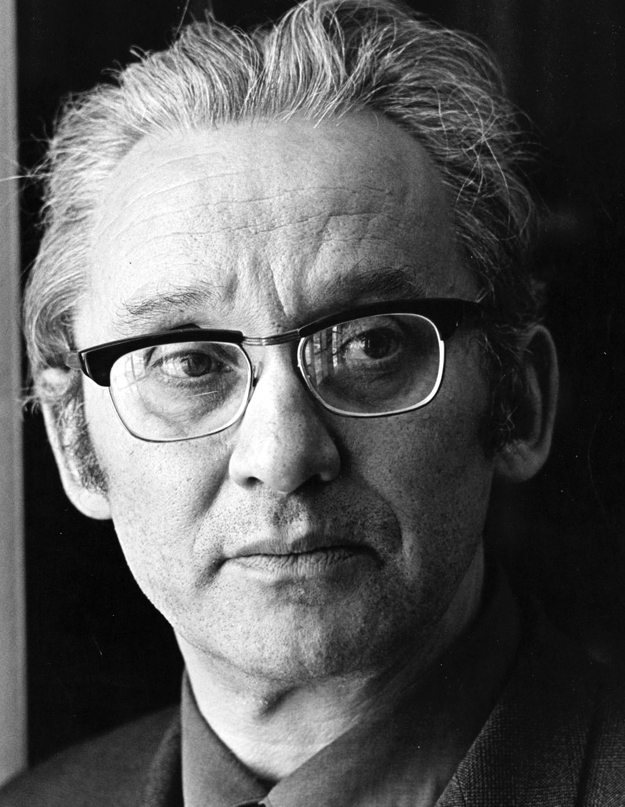

[Photo: Paul Ricoeur, circa 1970 upon his arrival at the University of Chicago, looking for all the world like the Hollywood icon, James Dean. University of Chicago News office: Detailed photo credit below.]

Ricœur’s intervention in the dynamics of academic politics and expanding the community of scholars the way he had done in setting up a kind of philosophy university in the German prisoner of war camp for his fellow French prisoners in 1941 did not work as well as he had hoped. Though it would not be fair to anyone (or to be taken out of context), the Germans (at that moment) were less violent than the striking French students and Peugeot workers in 1968. The French students threw tomatoes at Ricœur and called him a “old clown”; whereas the University of Chicago “threw” at him a prestigious named professorship. He liked the latter better. Ricœur’s courses were open to undergraduates who got permission, too, so I signed up for two of them – Hermeneutics and The Religious Philosophies of Kant / Hegel. Insert here a mind-bending blur of hundreds of pages of reading interspersed with dynamic and engaging presentations of the material. After the somewhat softball oral exams, for which he charitably gave me a pass, my head was spinning, and I needed to take a year off from school to regroup. I am not making this up. I worked as a parking lot attendant selling parking passes, which was an ideal job, since I could read a lot—you know, German-English facing pagination of two separate philosophical texts. This interruption also gave me time to go out for theatre to work on overcoming my painful social awkwardness and try and get a date with a girl. This “therapy” worked well enough, though, like most socially inept undergraduates, I had no skill at small talk and tended to utter what I had to say out of the blue and without creating any context. When I returned to school the next year to finish up, I proposed doing a bachelor’s thesis on Kant’s Refutation of Idealism, and I went into Professor Ricoeur’s office to make my proposal. Ricoeur was team teaching “Myth and Symbolism” with Mircea Eliade, and the “Imagination and Kant’s Third Critique” with Ted Cohen. Without any introductory remarks—I don’t think I even said my name—I presented the idea for my bachelor’s thesis. Without further chit-chit, raising one finger in the air for emphasis and smiling broadly, the first thing he said to me was: “An internal temporal flux implies an external spatial permanence.” With the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, I consider this a suitably empathic response, albeit an unconventional one. My paper eventually got published in the proceedings of the Acts of the 5th International Kant Congress. Fast forward a couple of years, comprehensive written exams in philosophy, and I proposed to write a PhD dissertation in philosophy on empathy [Einfühlung] and interpretation. Max Scheler’s Essence and Forms of Feelings of Sympathy [Wesen und Formen der Sympathiegefühl] contains significant material on empathy, and is (arguably) an early version of C. Daniel Batson’s collection of empathically-related phenomena. I was reading it with Professor Ricœur. Meanwhile, a psychoanalysis named Heinz Kohut, MD, like so many, a refugee from the Nazis, was innovating in empathy in the context of what was to become Self Psychology. I told one of the faculty at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis who was a mentor to me (and a colleague of Kohut), Arnold Goldberg, MD, about Ricœur’s Freud and Philosophy. Whether at my instigation or on Dr Goldberg’s own initiative (Ricoeur really needed no introduction from me), Dr Goldberg introduced Professor Ricoeur to the editors at the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association (JAPA) and the result was Ricœur’s publication “The Question of Proof In Freud’s Psychoanalytic Writings” in JAPA August 1977 [Volume 25, Issue 4 6517702500404]. Using graduate students as a good occasion for a conversation to build relationships, we all then had dinner at the Casbah, a middle eastern restaurant on Diversey near Seminary Avenues in Chicago’s Old Town.

It always seemed to me that Professor Ricoeur was a teacher of incomparable empathy, though he rarely used the word, at least until I started working on my dissertation on the subject of empathy and interpretation. I am pleased, indeed honored, to be able to elaborate the case here, while also defending Ricœur’s hermeneutics of suspicion from a misunderstanding that has shadowed the term since Toril Moi’s discussion (2017) of it at the University of Chicago colloquium on the topic shortly before the pandemic, the details of which are recounted in the article.

ricouerempathyinthecontextofsuspicionDownload

ABSTRACT: This essay defends Paul Ricoeur’s hermeneutics of suspicion against Toril Moi’s debunking of it as a misguided interpretation of the practice of critical inquiry, and we relate the practice of a rigorous and critical empathy to the hermeneutics of suspicion. For Ricoeur, empathy would not be a mere psychological mechanism by which one subject transiently identifies with another, but the ontological presence of the self with the Other as a way of being —listening as a human action that is a fundamental way of being with the Other in which “hermeneutics can stand on the authority of the resources of past ontologies.” In a rational reconstruction of what a Ricoeur-friendly approach to empathy would entail, a logical space can be made for empathy to avoid the epistemological paradoxes of Husserl and the ethical enthusiasms of Levinas. How this reconstruction of empathy would apply to empathic understanding, empathic responsiveness, empathic interpretation, and empathic receptivity is elaborated from a Ricoeurian perspective.

Photo credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf digital item number, e.g., apf12345], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

This blog post and web site (c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Review: The varieties of empathy in Richard Wright’s (1940) novel Native Son

Review: The varieties of empathy in Richard Wright’s (1940) novel Native Son(New York: Harper Perennial 504 pp + end matter)

The varieties of empathy and empathic experiences extend from authentic empathic receptivity, empathic understanding, and empathic responsiveness, all the way to fake empathy and mutilated empathy. Wright’s novel, Native Son, provides abundant examples of how empathy breaks down into emotional contagion, conformity, projection, and communications getting lost in translation. Of course, once empathy breaks down and fails, strictly speaking, it is no longer empathy and calls for a response to “clean up” the misunderstanding out of which a rigorous and critical empathy is restored and reestablished. Nevertheless, the varieties of empathically related phenomena that are constellated makes Wright’s classic work a study in empathy in all its diverse forms.

Native Son is as powerful and timely as it was when Richard Wright first published it in 1940. Though it has aspects of tragedy and traffics in ruin and wreck, in the final analysis, it has as much in common with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as it does with ancient Greek tragedy by Aeschylus, Sophocles, or Euripides.

The novel has not changed since 1940, but the world has – becoming both better and worse. To open up the reader’s historical empathy, a background report will be useful and is provided. This report also provides a chapter in African American history. The engagement with Native Son will be interspersed in this review with historical details that bring to life the power of the story in ways that might not be appreciated without a firm historical grounding. This is not a digression but of the essence, lest we forget how far we have come, and how far we still have to go to expand empathy and attain social justice.

The world has become better in that the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown versus the Board of Education (1954) that separate, segregated education in grammar and high schools is inherently

unequal. That is worth repeating: Separate but equal is inherently unequal. The world has become better in that the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act (1965/1965) were passed by a super majority of Congress. These outlawed segregation by law, also called “Jim Crow”; these enabled county and congressional districts in the South (or anywhere) with majority black populations to register to vote and elect black sheriffs and local officials. Why could they not do so previously? There were discriminatory poll taxes, which the impoverished people could not afford to pay; there were written tests (including trick questions) which people who lacked reading skills or merely had a grammar school education were unable to pass; there were other bureaucratic obstacles including the need to present state issued documents that were hard to obtain, putting the would-be voter in a double bind. One hastens to add that the struggle for social and political justice continues, with the US Supreme Court (2023) requiring Alabama and Georgia to redraw their gerrymandered congressional districts to allow for majority black districts. Under backward steps, the so-called “war on drugs” – espoused by Nancy Reagan and implemented by the Clinton administration, resulted in the incarceration (still ongoing) of a generation of young black men for relatively victimless crimes involving using crack cocaine.

Meanwhile, schools of all kinds continue to be under stress because of mass casualty gun violence. Teaching is a tough job, especially elementary and middle schools and it has gotten tougher; the bureaucratic requirements to present politically correct curriculum has pushed out fundamental skills of critical thinking along with skills such as the three R-s – reading, writing and (a)rithmetic. These have been replaced by the need for librarians and administrators to act in the role of surveillance state capitalism (see Zuboff 2018), overseeing whether some text refers to “gay,” “trans,” the name of a sex organ, and so on, and that someone – especially a parent – might be made to feel uncomfortable. To be sure, parents and educators need to be sensitive to the stages of child development and present material that fits the stage at which the growing child is maturing.

While Jim Crow is a historical reference and black empowerment is advancing, at times haltingly, the number of unarmed black people who end up dead after encounters with the local police has astonished everyone – everyone except black people who have known all about it all along. Today the number of black CEOs of major corporations is some 5.9 % out of an overall black population of 13.6% (US Census). That is progress since 1940 when Wright’s work was published, at which time the percentage was essentially zero. Johnson Publications, the publisher of Ebony magazine (among others), would not be founded until 1942. Yet a case can be made that, though many of the social and legal details are different, the need for struggle and protest is as powerful today as it was in 1940. We are not living in a post racial society, notwithstanding fact of having had a black president. All this and more may usefully inform our reading of Native Son.

Now to the narrative. The protagonist, Bigger Thomas (henceforth referred to as “BT”), completes the 8thgrade. He is too poor to continue school, nor is he motivated to do so. He experiences segregation and prejudice wherever he turns, as indeed do all black people. BT says, “Hell, it’s a Jim Crow army. All they want a black man for is to dig ditches. And in the navy, all I can do is wash dishes and scrub floors” (1940: 353). BT is not allowed to become a pilot or a tank driver or a professional. “I wanted to be an aviator once. But they wouldn’t let me go to the school where I was suppose’ to learn it. They built a big school and then drew a line around it and said that nobody could go to it but those who lived within the line. That kept all the colored boys out” (1940: 353). It is true there were a few exceptions – some black people go to college and become doctors, lawyers, or engineers, though how they pulled that off is not for the faint of heart.

However, basically, the form of life under segregation (Jim Crow) does not just lack possibility – the possibility of possibility itself is missing. Possibility is not even defined. What does that mean? For example, as soon as Barak Obama was elected US President, the media went to middle schools and interviewed black ten-year-old children about what they wanted to be when they grew up. They immediately knew they wanted to be President. Now this little different than wanting to be a cowboy or a fireman or a doctor, a child’s fantasy. The point is that prior to Obama’s election the possibility could not even be imagined by black children, excepting perhaps some weird science fiction scenario. That is what is meant by the possibility of possibility. BT lacks the possibility of possibility.

What happens in the narrative after BT serendipitously gets a “good job” as a chauffeur with a wealthy white family, shows that BT still does not “get” – understand or experience – the possibility of possibility. BT is so constantly in survival mode that, in trying to survive, he does the very thing that causes his tragic undoing. It is a well-known stereotype that whenever a black man is lynched or otherwise “taken down” socially, he is initially accused of assaulting or trying sexually to molest a white woman.

Who Is BT as a person and as a possibility at the start of the story? He is bully and a petty criminal. Malcolm Little, who became Malcolm X, was eleven years old when Wright began working on Native Son in 1936. Both BT and Malcolm, each in their own way, started out as petty criminals. Malcolm was arrested and went to prison. Malcom was the only person I ever heard of who said that prison made him better – indeed saved his life – because he met a follower of a version of strict Islam that enabled him to turn his life around, channeling his intelligence and leadership skills into black empowerment (though, ultimately, it also eventually led to his undoing in a tragedy of betrayal).

Meanwhile, in Native Son, Mary Dalton is the young adult daughter of the wealthy Henry Dalton, who has given some $5 million dollars to the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) while continuing to operate inner city slums overcrowded with blacks who are unable to rent or buy in other neighborhoods due to red lining and restrictive covenants (contracts) that prevent selling to black people. Moral ambiguities and flat-out hypocrisy are front and center. Henry’s wife is blind – she cannot see – and walks about the mansion dressed in white like a ghost. Everyone else in the novel – black and white – can see well enough – are visually unimpaired – but have blind-spots and unconscious biases sufficient to sink the Titanic. They do. Full speed ahead into the field of ice bergs!

Mary is an undergraduate at the local university near their mansion on Drexel Blvd. As a part of her late adolescent rebellion, she goes for the kind of boyfriends most calculated to shock her parents. She likes those “bad boys.” In this case, that would be the left wing radical and card carrying communist, Jan. On background, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti – Sacco and Vanzetti – were executed in the electric chair in 1927 for being anarchists, amid anti-Italian and anti-immigrant hysteria, not for the robbery and murder of which they were convicted and did not commit.

Wright was authoring at a time (circa 1936) when the Great Depression was still very much an economic reality. The Mayor was a machine boss, who would respond to crime waves by rounding up Communists and Negros. The Governor would call out the National Guard to put down workers who tried to form a union and go out on strike. The blacklisting of workers, both white and black (but mostly white because the blacks did not have jobs), who attempted to form unions was common, which meant they could not find work. Corporations stockpiled tear gas, vomit gas, ammunition and machine guns for armed strike breakers to use against railroad, steel, and manufacturing workers who dared to go out on strike. The National Labor Relations Board was not even validated by the US Supreme Court until 1937 in NLRB v. Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation, 301 U.S. 1 (1937). The forty-hour work week did not become law until the Fair Labor Standards Act (29 U.S. Code Chapter 8) was first enacted in 1938 under President Roosevelt’s New Deal.

This was a different world from 2023 and being a “Communist” meant something different than it does today, when, in the wake of the success of the trade union movement, much of what the original movement sought to accomplish (such as the 40 hour work week, sick leave, paid overtime, etc.) is part of standard legal labor law practice, rendering The Party irrelevant. Nevertheless, Mary and her boyfriend, Jan, a committed Communist, saw a common cause between the oppressed workers and the oppressed black people, and in this they were accurate enough, but naïve and idealistic, even utopian, in what it was going to take to make a difference.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions – and fake empathy. The privileged daughter, Mary, of the wealthy real estate tycoon (Mr Dalton), wants something from her new chauffeur. Remember, BT has just got a new, good paying job as the chauffeur. Mary wants him (BT) to ignore orders from her father, BT’s employer, and drive her around town with her boyfriend instead of to the University. Mary uses him (BT) as she would any extension of her own self-interest. For Mary, BT is an extension of her narcissism. BT later reports on his first encounter with Mary:

“She acted and talked in a way that made me [BT] hate her [Mary]. She made me feel like a dog. I was so mad I wanted to cry [. . . .] Mr Max, we’re all split up. What you say is kind ain’t kind at all. I didn’t know nothing about that woman. All I knew was that they kill us for women like that. We live apart. And then she comes and acts like that to me” (1940: 35).

The “acted like that” is the fake empathy – it seems kind enough on the surface in that the language does not have any devaluing words; yet there is a subtext – a soft violence, a quiet aggression, a conversational implicature that wrappers the relationship in BT’s subordination. “Acted like that” may also have a seductive aspect to it in that “being nice” in a situation where “no contact” is the norm may easily be misinterpreted as romantic flirting. The latter is not explicit in the text, but one thing is clear: BT and Mary Dalton really are the moth and the flame. Naivete and innocence are abundant on all sides. The moth has an automatic, hypnotic-like attraction to the flame. Little does the moth know what awaits. Does the flame have empathy for the moth? No, the flame is just the flame, towards which the moth has a luminously-based incentive that is its incineration. On background, the US Supreme Court finally ruled in Loving v Virginia in 1967 that anti-miscegenation laws, prohibiting marriage between whites and blacks (among others), were unconstitutional.

BT has survived on the street among white people by saying “Yessum; it’s all right with me” (1940: 64) and doing as he is told, and (in effect) justifying it by saying he was following orders. Recall, this is 1938 and that statement will come to have a different meaning in 1963 as Hannah Arendt reports for The New Yorker magazine on the trial of one Adolph Eichmann, who said something similar regarding the Holocaust. “I was just following orders.” There is nothing wrong with a chauffeur following orders, yet, in this case, “following orders” from Mary because she is white is an integrity outage in relation to his employment agreement with Mr Dalton to drive Mary to school. BT’s relationship to his word is as “fast and loose” as a rabbit randomly zig-zagging to try to survive by escaping a predatory fox.

Mary tells him “After all, I’m on your side” (1940: 64), and BT was not even aware of the possibility that changing side was imaginable – that there was a gate in the wall between rich and poor, educated and uneducated, employed and unemployed – mostly white and black. BT is getting $25 dollars a week and a pound of pork chops costs 5 cents ($.05), so that is a good wage. BT is in touch with his own self-interest, which is to keep his job so he can help himself and his mother and siblings. Yet something is off:

“Now, what did that mean? She was on his side. What side was he on? Did she mean that she liked colored people? Well, he [BT] had heard that about her whole family. Was she really crazy? How much did her folks know of how she acted? But if she were really crazy, why did Mr Dalton let him drive her out? [….]

“She was an odd girl, all right. He [BT] felt something in her over and above the fear she inspired in him. She responded to him as if he were human, as if he lived in the same world as she. And he had never felt that before in a white person. But why? Was this some kind of a game? The guarded feeling of freedom he had while listening to her was tangled with the hard fact that she was white and rich, a part of the world of people who told him what he could and could not do” (1940: 64, 65).

If someone tells you something that is too good to be true, it probably is. The ancient Greeks besieging Troy give up, sail off, and leave behind a giant horse as a gift to the gods. Casandra throws a spear at it, and it makes a hollow sound – thwomp! “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts!” No one believes her. Things do not work out well for the Trojans. “After all, I’m on your side.” The blind Mrs Dalton, walking around the mansion in her ghostly white gown, is the ineffective prophet, representing the blindness of all the players.

“Fake empathy” is defined here as a form of empathic responsiveness in which the person(s) claiming to be empathic towards the Other believe their own BS (bunkum, baloney, balderdash), endorse their own malarky, and, in effect, are sincerely self-deceived about the conflict of interest in which they are engaged. In another context, “fake empathy” could mean being intentionally deceptive as when a used car salesman knows the auto is defective but represents it as being in excellent shape. In most cases, the problematic sales person believes his or her own lies and could pass a lie detector test, which, of course, does not detect lies, but merely physiological arousal due to the stress of trying to deceive.

Mary wants BT to hide the facts from her father (that she is not gong to night school but out on the town with her “bad boy” community friend Jan). This puts BT at risk of losing his job. Mary acts in such a way as to claim to be on BT’s side, which is accurate enough in that she endorses racial integration and rights for workers, while seemingly remaining uninformed about the monopoly rents collected from black people by her father’s South Side Real Estate Corporation. Yet how could she not know? Another blind spot. More deception and self-deception.

If a further example is needed, Mary’s fake empathy continues as an expression of naivete and projection:

“You know, Bigger [BT], I’ve long wanted to go into these houses,” she said, pointing to the tall, dark apartment buildings looming to either side of them, “and just see how your people live. You know what I mean? I’ve been to England, France and Mexico, but I don’t know how people live ten blocks from me. We know so little about each other. I just want to see. I want to know these people. Never in my life have I been inside of a Negro house. Yet they must live like we live. They’re human . . . . There are twelve million of them . . . ” (1940: 69–70; italics and ellipsis in the original)

In so far as Mary genuinely cares about her black neighbors, this is a first step, born of good, caring intentions. However, Mary’s privilege, naivete, and arrogance (this list is not complete) are obstacles to her empathy. Her empathy misfires as projection. Mary speaks to BT in the third person about the group of which he himself is a part. The condescension is so thick that BT’s street knife would not cut through it had he even thought to try. Mary says, “Yet they [black people] must live like we live,” and that is definitely not the case. BT lives with his mother and two younger siblings in a single room. The opening scene of the novel involves a battle with a large rat in the small single room. Thus, the building is rat infested. Mary lives in a mansion with multiple servants, including BT. Mary tries to take a walk in BT’s shoes, shifting points of view, but it does not work. She is unable to take off her own shoes, so to speak – she can only imagine a glamorous life of travel – and her empathic imagination is insufficient to have a vicarious experience of the grinding, dehumanizing, poverty of her black neighbors, which poverty lives in her blind spot.

In contrast to fake empathy, a rigorous and critical empathy examines its own blind spots, projections, and conflicts of interests. It knows that it can be inaccurate or misfire. By cleaning up its conflicts of interests, projections, emotional contagions, and/or messages lost in translation, empathy becomes critical and rigorous. Unfortunately, Mary does not live to have the opportunity to work through her fake empathy to a rigorous and critical one, and BT experiences this dawning realization as he awaits execution for killing her.

The reader may say, I want instant empathy. Like instant coffee, just add water and stir. Wouldn’t it be nice? Nor is anyone saying such a thing as “instant empathy” is impossible. It may work well enough in a pinch; but like instant coffee, the quality may not be on a par with that required by a more demanding or discriminating appreciation and taste.

Jan’s case is similar to Mary’s though more nuanced. Jan wants something from BT as does Mary, but Jan’s agenda is less individual and, as befits a Communist, guided by an analysis of class. Yet he is equally naïve and utopian. Driving along Chicago’s Lake Shore Drive, which offers a panoramic view of the tall buildings in the central city from the South Side, Jan remarks:

“We’ll own all that some day, Bigger,” Jan said with a wave of his hand. “After the revolution it’ll be ours. But we’ll have to fight for it. What a world to win, Bigger! And when that day comes, things’ll be different. There’ll be no white and no black; there’ll be no rich and no poor” (1940: 68).

Jan’s innocence can be measured in that he is not even a very good Communist – his economic analysis is badly flawed. Jan talks as if the Communist revolution will change ownership from the capitalist to the communists whereas any Communist will tell you that the revolution will bring about the abolition of private property. Yet even if he is not a good Communist, Jan is a good human being. His righteous indignation is functioning. Learning that BT’s father was killed in a riot (read “massacre”) targeting black people in the South, Jan says to BT:

“Listen, Bigger, that’s what we want to stop. That’s what we Communists are fighting. We want to stop people from treating others that way. I’m a member of the Party. Mary sympathizes. Don’t you think if we got together we could stop things like that?” [….] You’ve heard about the Scottsboro boys?” (1940: 75; quotations and italics in the original)

On back ground, in 1931 eight black young adults and one juvenile, The Scottsboro Boys, were falsely accused of raping two women. After examination by a medical doctor, no evidence of rape was found. None. The testimony of the women themselves was coerced in that they were involved in sketchy activities that might have opened them up to criminal charges. The young men were tried by an all-white male jury for rape and sentenced to death for it (except for the juvenile, who was sentenced to life in prison). The NAACP and the Communist Party provided legal assistance to the young men and stopped the State from executing them; but they had to endure long and unjust years in prison. The novel calls out the newspaper headline in bold type in referring to BT:

“AUTHORITIES HINT SEX CRIME. Those words excluded him [BT] utterly from the world. To hint that he had committed a sex crime was to pronounce the death sentence; it meant wiping out of his life even before he was capture; it meant death before death came, for the white men who read those words would at once kill him in their hearts” (1940: 243).

BT’s life unfolds in three phases. Phase 1 lasts until, BT puts a pillow over the face of an intoxicated Mary Dalston, in trying to keep Mary from crying out and giving away that he (a black man) is alone with a white woman, even more “incriminating,” in her bedroom. At best he will lose his job – before being lynched for “rape.” The latter is here defined as the white man’s projected fantasy of the black man’s sexual attraction to and on the part of the white woman, which fantasy must be eliminated by lynching the innocent black man. (See the appendix on the varieties of prejudice below.)

What actually happens when BT is left alone with Mary Dalton, who is completely drunk? Mary is sloppy drunk, and can barely stand. BT tries to help her to her bedroom – by supporting her up the stairs. Practically, he has to carry her. Mary’s blind mother, Mrs Dalton, an insomniac, is wandering about the mansion like a ghost. The reader can see trouble coming – suppose they are discovered together in the dark in or near the bedroom? BT tries to explain to his girlfriend Betsy what happened:

“I didn’t mean to kill her. I just pulled the pillow over her face and she died. Her ma came into the room and the girl was trying to say something and her ma had her hands stretched out, like this, see? [The mother, Mrs Dalton, is blind and could not see BT.] I was scared she was goin’ to touch me. I just sort of pushed the pillow hard over the girl’s face to keep her from yelling. He ma didn’t touch me; I got out of the way. But when she left I went to the bed and the girl … She … She was dead” (1940: 227; italics in the original).

This decisive event happens early on in the story. The reader can see it coming. Mary is drunk. BT is uncertain what to do. Mr Dalton did not clarify to the new chauffeur (who is an extension of the auto) that the “boss” is Mr Dalton, who seems to have a blind spot about his angelic daughter’s rebellious streak. The unconscious fantasy, the unconscious bias, is that a black man alone with a white woman, much less an intoxicated one, is the equivalent of statutory rape. Lies, damn lies, and total nonsense move the action forward. Every action that BT takes to avoid the false accusation advances the action in the direction of an even more tragic outcome. BT ends up smothering Mary in order to avoid being discovered with her and being falsely accused of rape (which, of course, will get one lynched). In BT’s conversation with his attorney, Mr Max, BT muses:

“They would say he had raped her and there would be no way to prove that he had not. That fact had not assumed important in his eyes until now. He stood up, his jaws tightening. Had he raped her? Yes, he had raped her [but, of course, not literally]. Every time he felt as he had felt that night, he raped. But rape was not what one did to women. Rape was what one felt when one’s back was against a well and one had to strike out, whether one wanted to or not, to keep the pack from killing one. He committed rape very time he looked into a white face. He was a long, taut piece of rubber which a thousand white hands had stretched to the snapping point, and when he snapped it was rape. But it was rape when he cried out in hate deep in his heart as he felt the strain of living day by day. That, too was rape.” (1940: 227 – 228)

BT’s lawyer (Mr Max) tells the judge at BT’s trial:

“…[T]hat night a white girl was present in a bed and a Negro was standing over he, fascinated with fear, hating her; a blind woman walked into the room and that Negro [BT] killed that girl to keep from being discovered in a position which he knew we claimed warrants the death penalty” (1940: 400).