Home » Uncategorized

Category Archives: Uncategorized

A short talk on trauma and radical empathy

Without pretending to do justice to the vast research on “trauma,” it is variously defined as an event that threatens the person’s life and limb, making the individual feel he or she is going to die or be gravely injured (which would include rape). The blue roadside signs here in the USA that guide the ambulance to the “Trauma Center” (emergency department that has staff on call 7×24), suggest an emergency, usually but not always, a physical injury.

Cathy Caruth (1996) concisely defines trauma in terms of an experience that is registered but not experienced, a truth or reality that is not available to the survivor as a standard experience. The person (for example) was factually, objectively present when the head on collision occurred, but, even if the person has memories, and would acknowledge the event, paradoxically, the person does not presently experience it as something the person experienced in a way that a person standardly experienced the past event. The survivor experiences dissociated, repetitive nightmares, flashbacks, and depersonalization.

[Image credit (WIkimedia): Printmaker: Image: Prometheus being “traumatized” by the Vulture as punishment for giving the gift of fire to humanity (“mankind”): Cornelis Cortnaar Antwerp van: Titiaan (publisher of object), verlener van privilege: onbekend (vermeld op object)

Plate published: Rome

Date: 1566]

Strictly speaking, the challenge is not only that the would-be empathizer was not with the surviving Other when the survivor experienced the life-threatening trauma, but the survivor was physically present yet did not have the experience in such a way as to experience it. That may sound strange that the survivor did not experience the experience. Once again, one searches for words to capture an experience one did not experience. That is Caruth’s (1996) definition of “unclaimed” experience.

At the risk of oversimplification, Caruth’s work aligns with that of Bessel van der Kolk (2014). Van der Kolk emphasizes an account of trauma that redescribes in neuro-cognitive terms an event that gets registered in the body—burned into the neurons, so to speak, but remains sequestered—split off or quarantined— from the person’s everyday going on being and ordinary sense of self. The self is supposed to be a coherent unity—another example of a regulative idea—but a component of the self is split off due to a hypothetical, unknown traumatic cause. For both Caruth and van der Kolk, the survivor is suffering from an unintegrated experience of self-annihilating magnitude for which the treatment—whether working through, witnessing, or (note well) artistic engagement—consists in reintegrating that which was split off because it was simply too much to bear.

This artistic engagement with trauma has been described as “writing trauma,” for example, by Dominick LaCapra:

Trauma indicates a shattering break or caesura in experience which has belated effects. Writing trauma would be one of those telling after-effects in what I termed traumatic and post-traumatic writing (or signifying practice in general). It involves processes of acting out, working over, and to some extent working through in analyzing and ‘giving voice’ to [it] [. . . ]—processes of coming to terms with traumatic ‘experiences’, limit events, and their symptomatic effects that achieve articulation in different combinations and hybridized forms. Writing trauma is often seen in terms of enacting it, which may at times be equated with acting (or playing) it out in performative discourse or artistic practice (LaCapra 2001: 186–187).

Without intending to do so, LaCapra has unwittingly described Beloved (1987) (see Chapter 11), where the infant of the infanticide is literally reincarnated, reborn, in the person named “Beloved.” For LaCapra, working through such traumatic events is necessary for the survivors (and the entire community) in order to get their power back over their lives and open up the possibility of a future of flourishing. This “working through” is key for it excludes denial, repression, suppression, and, in contrast, advocates for positive inquiry into the possibility of transformation in the service of life. Yet the attempt at working through of the experiences, memories, nightmares, and consequences of such traumatic events often result in repetition, acting out, and, LaCapra’s key term, “empathic unsettlement.”

Such unsettlement is a challenge and an obstacle for the witness, therapist, or friend providing a gracious and generous listening. From a place of safety and security, the survivor has to do precisely that which she or he is least inclined to do—engage with the trauma, talk about it, try to integrate and overcome it. According to LaCapra, the empathic unsettlement points to the possibility that the vicarious experience of the trauma on the part of the witness leaves the witness unwilling to complete the working through, lest it “betray” the survivor, invalidate the survivor’s suffering or accomplishment in surviving.

Those traumatized by extreme events as well as those empathizing with them, may resist working through because of what might almost be termed a fidelity to trauma, a feeling that one must somehow keep faith with it” (LaCapra 2001: 22).

This “unsettlement” is a way that empathy breaks down, misfires, goes off the rails, resulting in empathic distress (Hoffman 2000). “Keeping faith with trauma” means the trauma itself has become an uncomfortable comfort zone. Extreme situations require extreme methods to engage and break up the emotional tangle.

Thus, according to Ruth Leys (2000), the traumatic events are “performed” in being written up as history or made the subject of a literary artwork. But the words, however authentic, true, or artistic, often seem inadequate, even fake. The “trauma” as brought forth as a distinction in language is ultimately inadequate to the pain and suffering that the survivor has endured, which “pain and suffering” are honored with the title of “the real” (as Kant might say). For Leys, the distinction “trauma” itself is inherently unstable oscillating between historical trauma—what really happened, which, however, is hard if not impossible to access accurately—and, paradoxically, literary language bearing witness by a failure of witnessing.

Moral trauma adds a challenging twist to what is traumatic about trauma. What is little recognized is that many survivors are also perpetrators (and vice versa). The survivor may also unwittingly (or even intentionally) become a perpetrator. The incarcerated prisoner of conscience steals a piece of bread from another prisoner, or to save his own life, falsely accuses another. One wants to say: This is tragic in the strict sense. Oedipus, Phaedra, Medea, practically the whole House of Atrius, are all both survivors and perpetrators.

Moral trauma is defined as the distressing emotional, behavioral, social, and sometimes spiritual aftermath of exposure to (including participation in) events in which a person’s moral boundaries are violated and in which individuals or groups are gravely injured, killed, or credible threat thereof is enacted (i.e., individuals are physically traumatized) (Litz et al 2009; see also Shay 2014). Examples of moral trauma include such things as being put in a situation where “I will kill you if you do not kill this person.” Generalizing on the latter example, the list includes morally fraught instances of double binds, valid military orders that result in unintentional harm to innocent people, situations in which survivors become perpetrators (and vice versa), soul murder (defined as killing the possibility of empathy and/or killing the possibility of possibility), and the Trolley Car Dilemma (Anonymous Wikipedia Content 2012, Foot 1967, Thomson 1976; see Chapter 11, Section: “The Trolley Car Dilemma and empathy”). In moral trauma people become both perpetrators and survivors, and such an outcome is characteristic of many (though not all) moral traumas.

Here radical empathy comes into its own. A person is asked to make a decision that no one should have to make. A person is asked to make a decision that no one is able to make—and yet the person makes the decision anyway, even if the person does nothing, because doing nothing is making a decision. A person is asked to make a decision that no one is entitled to make, which include most decisions about who should live or die (or be gravely injured). The result is moral trauma—the person is both a perpetrator and a survivor. Now empathize with that. No one said it would be easy.

Hence, the need for radical empathy. Extreme situations—that threaten death or dismemberment—call forth radical empathy. Standard empathy is challenged by extreme situations out of remote, hard-to-grasp experiences to become radical empathy.

The treatment or therapy consists of the survivor re-experiencing the trauma vicariously from a place of safety, an empathic space of acceptance and tolerance. In doing so the trauma starts losing its power and when it returns, it does so with less force, eventually becoming a distant unhappy and painful but not overwhelming memory.

For further reading, see van der Kolk 2014; LaCapra 2001; Leys 2000; Caruth 1995, 1996; Scarry 1985, Freud 1920.) See also Agosta (2025) Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature, Chapter 11, Sections: “The Trolley Car Dilemma and empathy” and “The four horsemen arrive.”

References

Lou Agosta. (2025). Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature, Chapter 11, Sections: “The Trolley Car Dilemma and empathy” and “The four horsemen arrive.” New York: Palgrave.

Anonymous Wikipedia Content. (2012). Trolley problem (The trolley dilemma). Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem [checked 2023-06-25]

Cathy Caruth. (1996). Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

Philippa Foot. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of the double effect. Oxford Review, No. 5. In Foot, 1977/2002, Virtues and Vices and Other Essays in Moral Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2002: 19–32. DOI:10.1093/0199252866.001.0001.

Sigmund Freud. (1920). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. The Standard Edition, Vol 18, New York and London: W.W. Norton: 1–64.

Martin L. Hoffman. (2000). Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP.

Dominick LaCapra. (2001). Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore: John Hopkins.

Ruth Leys. (2000). Trauma: A Genealogy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

B. T. Litz et al Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009 Dec;29(8):695-706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. Epub 2009 Jul 29. PMID: 19683376.

Elaine Scarry. (1985). The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford UP.

J. Shay, (2014). Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036090

Judith Jarvis Thomson. (1976). Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem, The Monist, vol. 59: 204–217.

Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking Press.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD, and The Chicago Empathy Project

How I changed my relationship with pain

Expanded power over pain is a significant result that may usefully be embraced by all human beings who experience pain – which describes just about everyone at some time or another. Acute pain communicates an urgent need for intervention; chronic pain is demoralizing and potentially life changing. Intervention required!

People who do not experience standard amounts of pain are at risk of hurting themselves. Dr. James Cox, senior lecturer at the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research at University College London, notes, “Pain is an essential warning system to protect you from damaging and life-threatening events” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat2019)). Admittedly not experiencing pain is a rare and concerning condition from which few of us suffer. Hence the practical approach considered here for the rest of humanity.

I changed my relationship to pain by working on the relationship. The result is that less pain occurs in my life and the pain that I do experience does not dominate my life. If one is completely pain-free, one is probably dead, which has different issues.

The following behaviors made a difference. Regular exercise, healthy diet, spiritual discipline (I have trained extensively in Tai Chi, but Yoga and/or meditation encompass the same results), consultations with professionals of one’s choice including medical doctors; and, here is the wild card, the purpose of this post: education in the different types of pain, including but not limited to acute pain versus chronic pain. The reader may say, “Holy cow! That’s too much work!” However, if the reader is in enough pain, then consider the possibility. What’s the alternative? Continue to suffer? Medically assisted suicide (where legal)? Opioids? The latter in particular have a place in hospice (end of life scenarios), in the week after surgery, but otherwise they are a deal with the devil. And, in any deal with the devil, be sure to read the fine print. “At a time when about 130 American die daily from opioid overdoses, scientists and drug companies are actively pursuing alternative non-opioid medications for acute and chronic pain” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat 2019)).

An example will be useful. I changed my relationship to pain, following my MDs guidance, by taking a double dose of NSAIDs – non steroidal anti-inflammatory “pain killers”. The idea is to “kill” the pain without killing the patient. This is no joke because NSAIDs such as Aleve can damage the mucous membranes of the gastro intestinal track (e.g., stomach), leading to ulcer-like conditions and the accompanying risks (not detailed here), which is why, even though they are over-the-counter, consultation with a medical doctor is important.

Doing Tai Chi changed my relationship to pain. Your mileage may vary, but I started to see results after ten weeks of dedicated daily work. My Tai Chi training has continued with one lengthy interruption for six years. My experience was the practice moved the pain threshold up. That is, I did not experience pain as acutely and when I did experience pain, it did not bother me as much. This can be a double-edged consideration. For example, the Tai Chi exercise of “holding the ball” is a stress position. One really needs a picture to see what this is.

One stands there with one’s arms encompassing a large ball at about the level of one’s chest with one’s hips tucked slightly as if sitting back. One’s whole body is engaged and conditioned. After about ten minutes one starts to heat up and after about fifteen minutes one starts to sweat. This is Tai Chi, not Yoga, but Mircea Eliade discusses similar stress positions that generate Shamanic Heat (Eliade, (1964), Shamanism, translated Willard Trask. Princeton University Press (Bollingen)).

Now a word of caution regarding the pain threshold. I went for a dermatological treatment and I got burned, literally, (fortunately, not too seriously), because I did not say “Stop – it hurts!” Granted that most people want to experience less pain, it is important to not extinguish pain completely, because pain in its acute presentation is trying to tell one something – in this case, injury to one’s skin due to heat.

Here is another example. A colleague has an inflamed ankle. It throbs. It hurts. It is not fractured but imaging shows it is enflamed, stressed out. The thing is that this is not just the person’s sprained ankle – it is his whole life. Since he needs to lose weight, he needs to get exercise. Because he cannot get sufficient exercise, he cannot lose weight. The extra weight contributes to the ankle continuing to be stressed. Double-bind! Rock and the hard place. How is this individual going to break out of this tight loop? Now I know this is going to sound crazy, but here it is: Follow doctor’s orders! Go to the physical therapy! If you have got to wear “the boot” for a couple of weeks, do so. Start low (with the number of repetitions of exercises) – go slow. If the person had access to a swimming pool, that would be ideal, but that might not be workable for many people. SPA-like treatments, soaks in Epsom salts in sensory deprivation pods have value.

Many parallel examples can be cited in which a person knows exactly what she has to do (don’t even worry about the doctor) – why is the person not doing it? Many reasons exist, but one of them is that suffering becomes a comfort zone. Suffering is sticky. “Yes, I am miserable,” the individual says, but it is a familiar misery. Suffering has become an uncomfortable comfort zone. What would it take to give that up? Once one realizes, “This is what crazy looks like,” it becomes easier to give up the suffering. This is not a deep dive into the psychology of the unconscious, yet this is not merely a physical challenge. Yes, the ankle hurts – objectively, there is even an image that shows inflammation, albeit hazy and faint. However, even if there weren’t evidence of an injury – and soft tissue damage often escapes imaging, the emotional issue – ambivalence about one’s body image (“weight”) – gets entangled with the person’s whole life. In this case, a struggle with unhealthy excess weight – and the person’s emotions run with the ball – elaborate the injury psychologically. This is also a form of catastrophizing or awfulizing (made famous by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)), but CBT did not invent it.

I gave the example of an inflamed ankle, but it might also apply to lower back pain, headaches, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which are notoriously difficult to diagnose medically. Speaking personally, I want a quick fix. We all do. However, after a while, if the “fix” does not occur, there is no in principle limit on the amount of time and effort one can spend trying to find a quick fix. After a certain time, one gets a sense that one might put the time and effort into incremental progress – finding whatever moves the dial – whatever shifts the stuckness. Here’s what I did not want to hear: This is gonna take some work. After a time, one decides to roll up the sleeves and do the hard work need to get one’s power back. Healthy diet and a well-defined exercise program are important components. Finding an MD and/or health care provider including physical therapist where the interpersonal chemistry works is on the critical path to dialing down the suffering. Here “interpersonal chemistry” is another description for empathy. Look for someone whose empathy is open enough to encompass one’s pain and suffering without being coopted by it. This is the critical path to recovery.

The distinction between acute pain and chronic pain needs to be better understood by the average citizen. An excerpt from Neurology 101 may be useful. In acute pain, the peripheral nervous system in the body’s appendages such as one’s toes reports via neural connections to the central nervous system (e.g., the brain in one’s head). The impact of a heavy object such as a large brick with my toe releases neurotransmitters at the nociceptors (we are not talking Greek and “nocio” means “pain”). The mechanics are such that a message is delivered from the periphery to the center that what is in effect a boundary violation – an injury – has occurred. The brain then tells the toe to hurt – “Ouch!” The message is delivered seamlessly to the conscious person to whom the toe “belongs” in the neural map that associates the body with conscious experience unfolding in the person’s awareness. The toe which had quietly been doing its job in helping the person walk, balance, be mobile now makes a lot of “noise” – it starts throbbing. This is what acute pain feels like.

With chronic pain the scenario gets complicated. If the injury is subjected to other stressors, slow to heal, reinjured, or otherwise neglected, then the pain may continue across a period of days or weeks and become habitual. In effect, the pain signal becomes a bad habit. The pain takes on a life of its own. What does that even mean? What starts out as a way of reminding the person to attend to the injury gets stuck on “repeat”. Like the marketing company that keeps sending your notices even after you specify “Do not solicit!” The messaging is not just from the toe to the brain, from the periphery to the center, but it gets reversed. The messaging is from the center to the periphery, from the brain to the body part. The brain tells the periphery to hurt. Chronic pain becomes a source of suffering. Here “suffering” expands to include worry that anticipates and/or expects pain, which gets further reinforced when the pain actually shows up.

The poster child for chronic pain is phantom limb pain. Not all pains are created equal. Phantom limb pain provides compelling evidence that pain is “in one’s head” only in the sense that pain is in the brain and the brain is in one’s head. Only in that limited sense is pain in one’s head. Yet the pain is not imaginary. Documented as early as the American Civil War by Silas Weir Mitchell, individuals who had undergone amputation, felt the nonexistent, missing limb to itch or cramp or hurt. The individuals experienced the nonexistent tendons and muscles of the missing limb as cramping and even awakening the person from the most profound sleep due to pain (As noted, further in Haider Warraich. (2023). The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain. New York: Basic Books, pp. 110 – 111).

Fast forward to modern times and Ron Melzack’s gate control theory of pain marshals such phantom limb pain as compelling evidence that the nervous system contains a map of the body and the body’s pains point, which map has not yet been updated to reflect the absence of the lost limb. In effect, the brain is telling the individual that his limb is hurting using an obsolete map of the body – the memory of pain. Thus, the pain is in one’s head, but not in the sense that the pain is unreal or merely imaginary. The pain is real – as real as the brain that is indeed in one’s head and signaling (“telling”) one that one is in pain. (R. Melzack, (1974), The Puzzle of Pain. Basic Books.)

Whatever the level of pain, stress is probably going to make it feel worse. Therefore, stress reduction methods such as meditation, Tai Chi, Yoga, time spent soaking in a sensory deprivation pod, and SPA-like stress reduction methods are going to be beneficial in moving the pain dial downward.

One question that has not even occurred to scientists is whether it is possible to have the functional equivalent of phantom limb pain, even though the person still has the limb functionally attached to the body. This sounds counter-intuitive, but think about it. If there is a map of the body’s pain points in the central nervous system (the brain), there is nothing that says “phantom” pains cannot occur even if an appendage still exists. For example, the high school football player who needs the football scholarship to go to college because he is weak academically; he is not good at baseball, but actually hates football. He incurs a soft tissue sports injury, which gets elaborated due to emotional conflict about his ambivalent relationship with football, leaving him on crutches for far-too-long and both physically and symbolically unable to move forward in his life. As if the only three life choices are football, baseball, and academics?! Note that the description of the injury “painful soft tissue” already opens and shuts approaches to treatment. That is the devilish thing – what is the actual and accurate description? Thus, due to the inherent delays in neuroplasticity – the update to the brain’s map of the body is not instantaneous and one does not have new experiences with a nonexistent limb – pain takes on a life of its own.

Though an oversimplification, the messaging between the peripheral and central nervous systems is reversed. Instead of the peripheral limb telling the brain of a “hurt,” the brain develops a “bad habit” of signaling pain and tells the limb to hurt. That is the experience of chronic pain – pain has a life of its own – pain becomes the dis-ease (literally), not the symptom. What then is the treatment, doctor? Physical therapy (PT) – exercises to strengthen the knee and, in effect, teach him to walk again.

Chronic pain is discouraging, demoralizing, fatiguing, exhausting, negatively impacting one’s mental status. I have been cagey about my own experience of pain in this post, but it is a matter of record that I have osteoarthritis, a progressive deterioration of the cartilage in joints such as occurs in people who are getting older and who are long term runners. The person understandably and properly continuously asks himself – what am I experiencing? And does it include pain? No one is saying the “cure” is don’t think about it (pain), don’t worry about it. No one is saying “play hurt”? “Playing hurt” is a bad idea for so many reasons, including one is going to make a bad injury worse. Professional athletes who “play hurt” may indeed get a bunch of money, but they also often dramatically shorten their careers – and that costs them money.

While distraction from one’s pain can be useful in the short term, it is not a sustainable solution. Rather when, after medical determination of the sources of pain are determined to be unable to be completely extinguished or eliminated, one is saying undertake an inquiry into what one is really experiencing. Rather than react to the uncomfortable twinges and twitches, bumps and thumps, prodding and pokes, that one encounters, ask what one is really feeling. Undertake an inquiry into what one is experiencing. If, upon consideration, the answer is “The pain is acute going from 4 to 8 to 9 on the 10 point scale,” then stop and call for backup, including taking pain killers such as NSAIDS as recommended by an MD.

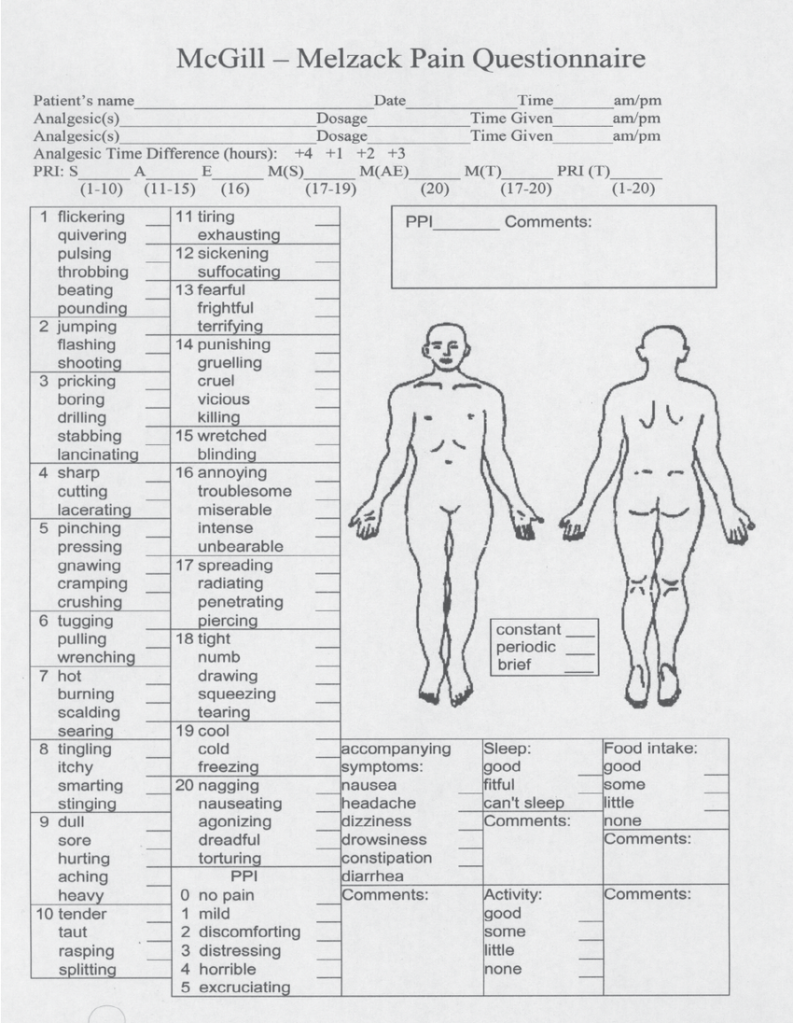

Here the vocabulary of pain is relevant. See Melzack’s McGill pain chart. [List the vocabulary]

Further background information will be useful. Haider Warraich, MD, in The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain (Basic Books, 2023) radicalizes the issue of pain that takes on a life of its own before suggesting a solution. After providing a short history of opium and morphine and opioids, culminating “in the most prestigious medical school on earth, from the best teachers and physicians, we [medical students] were unknowingly taught meticulously designed lies” (p. 185), that is, prescribe opioids for chronic pain. The reader wonders, where do we go from here? To be sure opioids have a role in hospice care and the week after surgery, but one thing is for certain, the way forward does not consist in prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

After reviewing numerous approaches to integrated pain management extending from cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to valium, cannabis and Ketamine – and calling out hypnosis (hypnotherapy) as a greatly undervalued approach (no external chemicals are required, but the issue of susceptibility to hypnotic suggestibility is fraught) – Dr Warraich recovers from his own life changing back injury in a truly “physician heal thyself” moment thanks to dedicated PT, physical therapy (p. 238). If this seems stunningly anti-climactic, it is boring enough to have the ring of truth earned in the college of hard knocks, but it is a personal solution (and I do so like a happy ending!), not the resolution of the double bind in which the entire medical profession finds itself (pp. 188 – 189). The way forward for the community as a whole requires a different, though modest, proposal. The patient signs up for and completes physical therapy (PT), a custom set of exercises tailed to his pain condition and mobility issues.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “The body is the best picture of the soul.” The default since René Descartes is to distinguish physical pain from psychic pain – what used to be called the difference between “body” and “soul” before science “proved” that the soul did not exist. (Once again, we are talking Greek “psyche” is the Greek word for “souI.”) Nevertheless, in spite of the “proof” that the soul does not exist, soul-like phenomena keep showing up. For example, if the person’s “soul” is regularly subjected to negative verbal feedback from those in authority, the person becomes physically ill – ulcers, headaches, lower back pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). As noted, these are notoriously difficult to diagnoses. The adverse childhood experience survey (ACE) provides solid evidence that psychic and moral injuries correlate significantly with major medical disorders (e.g., Felitti 2002).

One big issue is that we (science and scientists) lack a coherent, effective account of emergent properties. One with neurons. The alternative is the current reductive paradigm according to which, in spite of contrary assertions, on has trouble explaining that things really are what they seem to be – that table are tables andmade of microscopic components such as atoms. We start with neurons. We are neurons “all the way down.” Neurons generate stimuli; stimuli generate sensations/experiences; experiences generate [are] responses; responses form patterns; patterns generate meaning; meaning generates language. With the emergence of language, things really start to get interesting. Organized life reaches “take off” speed. Language generates community; community generates – or rather is functionally equivalent to – culture, art, poetry, science, technology, and the world as we know it.

What about individuals who are put in a double-bind by circumstances as when someone in authority makes a seemingly impossible demand? For example, the army Sargent gives what seems to be a valid military order to the corporeal to shoot at the rapidly approaching auto, thinking it is a suicide car bomb, but it is really an innocent family. The soldier, thinking the order is valid and that he is protecting his team, follows the order. The solider is now both a perpetrator and a survivor. People have gotten hurt who ought not to have been hurt. Moral inquiry. Moral trauma has occurred. Tai Chi is not going to save this guy. This take the form of guilt – which is aggression – hostile feeling and anger – turned against one self. The individual’s agency – the individual’s power as an agent to choose – is compromised by contingent circumstance, including the individual’s unavoidable choice in the circumstance, since taking no action is also a choice.

This is why the ancient Greeks invented tragedy. A careful reading of the Greek tragedies, which cannot be adequately canvassed here, shows that virtually every tragic hero has the compromised agency characteristic of a double bind. Oedipus is a powerful agent, yet compromised and brought low by inadequate information. Information asymmetries! Antigone’s agency is bound, doubly, by the conflict between the imperatives of politics and the integrity of family. Agamemnon’s agency is compromised by the negative aspect of honor and pride and an overweening narcissism. Iphigenia’s agency is compromised by literally being bound and gagged (admittedly a limit case). Double-binds have also been hypothesized to contribute to the causation of major mental illness (Bateson 1956). Contradictory messages from parents, explicit versus implicit, spoken versus unspoken, are particularly challenging. Here the fan out to related issues is substantial.

I changed my relationship to pain and suffering by reading all thirty existing Greek tragedies. One might say if something is worth doing, it is worth over-doing, and the reader might try starting with just one. Examples of pain and suffering occur in abundance: acute pain – Hercules puts on the poisoned cloak, which burns his flesh; chronic pain – Philoctetes has a wound that will not heal and throbs periodically with painful sensations; and suffering – Oedipus is misinformed about who is his birth mother and after having children with her he suffers so from his awareness of his violation of family standards that he mutilates himself, tearing his eyes out. The latter would, of course, be acute pain, but the cause, the trigger, is thinking about what he has done in relation to the expectations of the community, namely, violating the incest taboo.

Now, according to Aristotle, the representation of such catastrophes is supposed to evoke pity and fear in the audience (viewer) of the classic theatrical spectacle. Indeed, such spectacles – even though the violence usually happens “off stage” and is reported – are not for the faint of heart. We seem to want to identify with the characters in a narrative, which, in turn, activates our openness to their experiences in an entry level empathy that communicates a vicarious experience of the character’s struggle and suffering. Advanced empathy also gets engaged in the form of appreciation of who is the character as a possibility in relation to which the viewer (audience) considers what is possible in her of his own life. One takes a walk in the other’s shoes, after having taken off one’s own. Other examples of similar experiences include why (some) people like to see horror movies. One does not run screaming from the theatre, but conventionally appreciates that the experience is a vicarious one – an “as if” or pretend experience. Likewise, with “tear jerker” style movies – one gets a “good cry,” which has the effect of an emotional purging or cleansing.

Now I am not a natural empath, and I have had to work at expanding my empathy. In contrast, the natural empath is predisposed, whether by biology or upbringing (or both), to take on the pain and suffering of the world. Not surprisingly this results in compassion fatigue and burn out. The person distances him- or herself from others and displays aspects of hard-heartedness, whereas they are actually kind and generous but unable to access these “better angles.” It should be noted that empathy opens one up to positive emotions, too – joy and high spirits and gratitude and satisfaction – but, predictably, the negative ones get a lot of attention.

“Suffering” is the kind of thing where what one thinks and feels does make a difference. Now no one is saying that Oedipus should have been casual about his transgressions – “blown it off” (so to speak); and the enactment does have a dramatic point – Oedipus finally begins to “see” into his blind spot as he loses his sight. Really it would be hard to know what to say. Still, the voice of reality would council alternatives – other ways are available of making amends – making reparations – perhaps more than two “Our Fathers” and two “Hail Marys” as penance – what about community service or fasting? “Suffering” is not just a conversation one has with oneself about future expectations. It is also a conversation one has with oneself about one’s own inadequacies and deficiencies (whether one is inadequate or not). For example, unkind words from another are hurtful. In such cases what kind of “pain” is the hurt? We get a clue from the process of trying to manage such a hurt. The process consists in setting boundaries, setting limits, not taking the words personally (even though inevitably we do). The hurt lives in language and so does the response. Therefore, in an alternative scenario, one takes the bad language in and turns it against oneself. One anticipates a negative outcome. One gets guilt (once again, regardless of whether one has does something wrong or not).

The coaching? If you are suffering from compassion fatigue, then dial down the compassion. This does not mean become hard-hearted or mean. Far from it. This means do not confuse a vicarious experience of pain and suffering with jumping head over heels into the trauma itself. What may usefully be appreciated is that practices such as empathy, compassion, altruism are not “on off” switches. They are not all or nothing. Skilled executioners of these practices are able to expand and contract their application to suit the circumstances. To be sure, that takes practice. The result is expanded power over vicariously shared pain and suffering. One gets power back and is able to assist the other in recovering their power too. (Further tips and techniques on how to change one’s thinking and expand one’s empathy are available in my Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide (with 24 full color illustrations by Alex Zonis), also available as an ebook.)

Before concluding, I remind the reader that “all the usual disclaimers.” This is a personal reflection. The only data is my own experience and bibliographical references that I found thought provoking. “Your mileage may vary.” If you are in pain (which, at another level and for many spiritual people, is one definition of the human condition) or if you are in the market for professional advice, start with your family doctor. If you do not have one, get one. Talk to a spiritual advisor of your own choice. Above all, “Don’t hurt yourself!” This is not to say that I am not a professional. I am. My PhD is in philosophy (UChicago) with a dissertation entitle Empathy and Interpretation. I have spent over 10K hours researching and working on empathy and how it makes a difference. So if you require expanded empathy, it makes sense to talk to me. A conversation for possibility about empathy can shift one’s relationship with pain.

Bibliography

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J., 1956, Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, Vol. 1, 251–264.

Corley, Jacquelyn. (2019). The Case of a Woman Who Feels Almost No Pain Leads Scientists to a New Gene Mutation. Scientific American. March 30, 2019. Reprinted with permission from STAT. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-case-of-a-woman-who-feels-almost-no-pain-leads-scientists-to-a-new-gene-mutation/

Eliade, Mircea. (1964). Shamanism. Princeton University Press (Bollingen).

Felitti VJ. (2002). The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead. The Permanente Journal (Perm J). 2002 Winter;6(1):44-47. doi: 10.7812/TPP/02.994. PMID: 30313011; PMCID: PMC6220625.

Melzack, R. (1974). The Puzzle of Pain. New York: Basic Books.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Paul Ricoeur, Philosopher of Empathy

This article on Paul Ricoeur, empathy, and the hermeneutics of suspicion in literature will be engaging to students of Ricoeur and empathy alike. One can download the PDF directly from the journal Etudes Ricœeurienne / Ricoeur Studies website: http://ricoeur.pitt.edu/ojs/ricoeur/article/view/628

The article is in English and an abstract is cited below at the bottom. If the above link does not work for any reason, then scroll to the bottom, where one can download the PDF within this blog post.

Meanwhile, I offer a recollection of my personal encounter with Professor Ricœur starting when I was a third year undergraduate at the UChicago. (This is an excerpt from a pending manuscript on empathy in the context of literature.)

By the time I was an undergraduate in my junior year in college, Paul Ricoeur had just arrived at the University of Chicago. Professor Ricoeur had attempted to play a conciliatory role in listening to and addressing student grievances in the face of entrenched method of lecturing by ex cathedra by mandarin professors at the Sorbonne, Paris, France, and related schools in the system. Though Ricoeur did not use the word “empathy” in his role as administrator at the University of Nanterre, he was attempting to play a role in conflict mediation, during the strike of student and workers in Paris in May 1968, a role in which empathy is famously on the critical path.

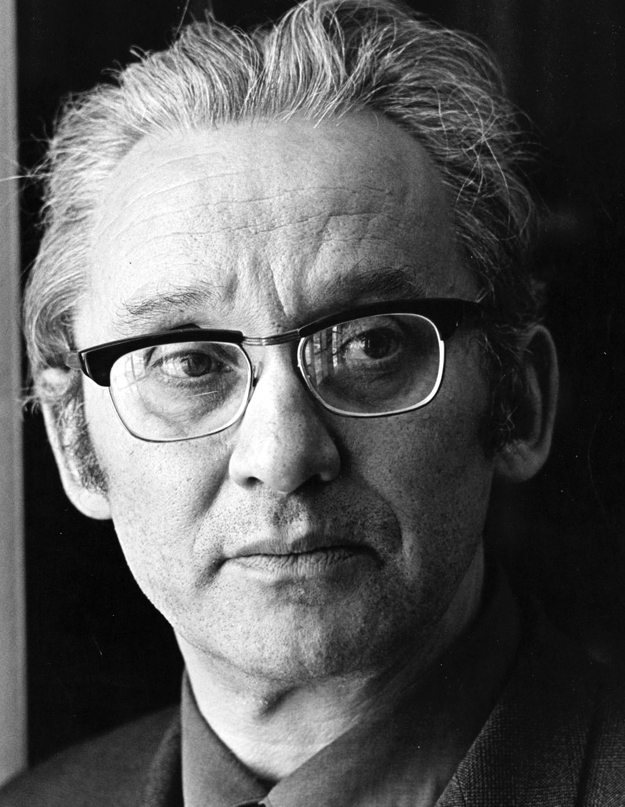

[Photo: Paul Ricoeur, circa 1970 upon his arrival at the University of Chicago, looking for all the world like the Hollywood icon, James Dean. University of Chicago News office: Detailed photo credit below.]

Ricœur’s intervention in the dynamics of academic politics and expanding the community of scholars the way he had done in setting up a kind of philosophy university in the German prisoner of war camp for his fellow French prisoners in 1941 did not work as well as he had hoped. Though it would not be fair to anyone (or to be taken out of context), the Germans (at that moment) were less violent than the striking French students and Peugeot workers in 1968. The French students threw tomatoes at Ricœur and called him a “old clown”; whereas the University of Chicago “threw” at him a prestigious named professorship. He liked the latter better. Ricœur’s courses were open to undergraduates who got permission, too, so I signed up for two of them – Hermeneutics and The Religious Philosophies of Kant / Hegel. Insert here a mind-bending blur of hundreds of pages of reading interspersed with dynamic and engaging presentations of the material. After the somewhat softball oral exams, for which he charitably gave me a pass, my head was spinning, and I needed to take a year off from school to regroup. I am not making this up. I worked as a parking lot attendant selling parking passes, which was an ideal job, since I could read a lot—you know, German-English facing pagination of two separate philosophical texts. This interruption also gave me time to go out for theatre to work on overcoming my painful social awkwardness and try and get a date with a girl. This “therapy” worked well enough, though, like most socially inept undergraduates, I had no skill at small talk and tended to utter what I had to say out of the blue and without creating any context. When I returned to school the next year to finish up, I proposed doing a bachelor’s thesis on Kant’s Refutation of Idealism, and I went into Professor Ricoeur’s office to make my proposal. Ricoeur was team teaching “Myth and Symbolism” with Mircea Eliade, and the “Imagination and Kant’s Third Critique” with Ted Cohen. Without any introductory remarks—I don’t think I even said my name—I presented the idea for my bachelor’s thesis. Without further chit-chit, raising one finger in the air for emphasis and smiling broadly, the first thing he said to me was: “An internal temporal flux implies an external spatial permanence.” With the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, I consider this a suitably empathic response, albeit an unconventional one. My paper eventually got published in the proceedings of the Acts of the 5th International Kant Congress. Fast forward a couple of years, comprehensive written exams in philosophy, and I proposed to write a PhD dissertation in philosophy on empathy [Einfühlung] and interpretation. Max Scheler’s Essence and Forms of Feelings of Sympathy [Wesen und Formen der Sympathiegefühl] contains significant material on empathy, and is (arguably) an early version of C. Daniel Batson’s collection of empathically-related phenomena. I was reading it with Professor Ricœur. Meanwhile, a psychoanalysis named Heinz Kohut, MD, like so many, a refugee from the Nazis, was innovating in empathy in the context of what was to become Self Psychology. I told one of the faculty at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis who was a mentor to me (and a colleague of Kohut), Arnold Goldberg, MD, about Ricœur’s Freud and Philosophy. Whether at my instigation or on Dr Goldberg’s own initiative (Ricoeur really needed no introduction from me), Dr Goldberg introduced Professor Ricoeur to the editors at the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association (JAPA) and the result was Ricœur’s publication “The Question of Proof In Freud’s Psychoanalytic Writings” in JAPA August 1977 [Volume 25, Issue 4 6517702500404]. Using graduate students as a good occasion for a conversation to build relationships, we all then had dinner at the Casbah, a middle eastern restaurant on Diversey near Seminary Avenues in Chicago’s Old Town.

It always seemed to me that Professor Ricoeur was a teacher of incomparable empathy, though he rarely used the word, at least until I started working on my dissertation on the subject of empathy and interpretation. I am pleased, indeed honored, to be able to elaborate the case here, while also defending Ricœur’s hermeneutics of suspicion from a misunderstanding that has shadowed the term since Toril Moi’s discussion (2017) of it at the University of Chicago colloquium on the topic shortly before the pandemic, the details of which are recounted in the article.

ricouerempathyinthecontextofsuspicionDownload

ABSTRACT: This essay defends Paul Ricoeur’s hermeneutics of suspicion against Toril Moi’s debunking of it as a misguided interpretation of the practice of critical inquiry, and we relate the practice of a rigorous and critical empathy to the hermeneutics of suspicion. For Ricoeur, empathy would not be a mere psychological mechanism by which one subject transiently identifies with another, but the ontological presence of the self with the Other as a way of being —listening as a human action that is a fundamental way of being with the Other in which “hermeneutics can stand on the authority of the resources of past ontologies.” In a rational reconstruction of what a Ricoeur-friendly approach to empathy would entail, a logical space can be made for empathy to avoid the epistemological paradoxes of Husserl and the ethical enthusiasms of Levinas. How this reconstruction of empathy would apply to empathic understanding, empathic responsiveness, empathic interpretation, and empathic receptivity is elaborated from a Ricoeurian perspective.

Photo credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf digital item number, e.g., apf12345], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

This blog post and web site (c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

The Empathy Diaries by Sherry Turkle (Reviewed)

Read the review as published in abbreviated form in the academic journal Psychoanalysis, Self, and Context: Click here

The short review: the title, The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir (Sherry Turkle New York: Penguin Press, 2021, 357 pp.) reveals that empathy lives, comes forth, in empathy’s breakdowns and failings. Empathy often emerges in clarifying a lack of empathy. This work might have been entitled, less elegantly, “The Lack of Empathy Diaries.” I found the book to be compellingly written, even a page-turner at times, highly recommended. But, caution, this is not a “soft ball” review.

As Tolstoy famously noted, all happy families are alike. What Tolstoy did not note was that many happy families are also unhappy ones. Figure that one out! Sherry’s answer to Tolstoy is her memoir about the breakthroughs and breakdowns of empathy in her family of origin and subsequent life.

Families have secrets, and one was imposed on the young Sherry. Sherry’s mother married Charles Zimmerman, which became her last name as Charles was the biological father. Within a noticeably short time, mom discovered a compelling reason to divorce Charles. The revelation of his “experiments” on the young Sherry form a suspenseful core to the narrative, more about this shortly.

Do not misunderstand me. Sherry Turkle’s mom (Harriet), Aunt Mildred, grand parents, and the extended Jewish family, growing up between Brooklyn and Rockaway, NY, were empathic enough. They were generous in their genteel poverty. They gloried in flirting with communism and emphasizing, in the USA, it is a federal offense to open anyone else’s mail. Privacy is one of the foundations of empathy – and democracy. Sherry’s folks talked back to the black and white TV, and struggled economically in the lower middle class, getting dressed up for Sabbath on High Holidays and shaking hands with the neighbors on the steps of the synagogue as if they could afford the seats, which they could not, then discretely disappearing.

Mom gets rid of Charles and within a year marries Milton Turkle, which becomes Sherry’s name at home and the name preferred by her Mom for purposes of forming a family. There’s some weirdness with this guy, too, which eventually emerges; but he is willing and a younger brother and sister show up apace.

In our own age of blended families, trial marriages, and common divorce, many readers are, like, “What’s the issue?” The issue is that in the late 1950s and early 1960s, even as the sexual revolution and first feminist wave were exploding on the scene, in many communities divorce was stigmatizing. Key term: stigma. Don’t talk about it. It is your dark secret. The rule for Sherry of tender age was “you are really a Turkle at home and at the local deli; but at school you are a Zimmerman.” Once again, while that may be a concern, what’s the big deal? The issue is: Sherry, you are not allowed to talk about it. It is a secret. Magical thinking thrives. To young Sherry’s mind, she is wondering if it comes out will she perhaps no longer be a part of the family – abandoned, expelled, exiled.

Even Sherry’s siblings do not find out about the “name of the father” (a Lacanian allusion) until adulthood. A well kept secret indeed. Your books from school, Sherry, which have “Zimmerman” written in them, must be kept in a special locked cupboard. How shall I put it delicately? Such grown up values and personal politics – and craziness – could get a kid of tender age off her game. This could get one confused or even a tad neurotic.

The details of how all these dynamics get worked out make for a page turner. Fast forward. Sherry finds a way to escape from this craziness through education. Sherry is smart. Very smart. Her traditionally inclined elders tell her, “Read!” They won’t let her do chores. “Read!” Reading is a practice that expands one’s empathy. This being the early 1960s, her folks make sure she does not learn how to type. No way she is going to the typing pool to become some professor’s typist. She is going to be the professor! This, too, is the kind of empathy on the part of her family unit, who recognized who she was, even amidst the impingements and perpetrations.

Speaking personally, I felt a special kinship with this young person, because something similar happened to me. I escaped from a difficult family situation through education, though all the details are different – and I had to do a bunch of chores, too!

The path is winding and labyrinthine; but that’s what happened. Sherry gets a good scholarship to Radcliffe (women were not yet allowed to register at Harvard). She meets and is mentored by celebrity sociologist David Riesman (The Lonely Crowd) and other less famous but equally inspiring teachers.

Turkle gets a grant to undertake a social psychological inquiry into the community of French psychoanalysis, an ethnographic study not of an indigenous tribe in Borneo, but a kind of tribe nonetheless in the vicinity of Paris, France. The notorious “bad boy” Jacques Lacan is disrupting all matters psychoanalytic. His innovations consist in fomenting rebellion in psychoanalytic thinking and in the community. “The name of the father” (Lacan’s idea about Oedipus) resonates with Turkle personally. Lacan speaks truth to [psychoanalytic] power, resulting in one schism after another in the structure of psychoanalytic institutes and societies.

Turkle intellectually dances around the hypocrisy, hidden in plain view, but ultimately calls it out: challenging authority is encouraged as long as the challenge is not directed at the charismatic leader, Lacan, himself. This is happening shortly after the students and workers form alliance in Paris May 1968, disrupting the values and authority of traditional bourgeois society. A Rashomon story indeed.

Turkle’s working knowledge of the French language makes rapid advances. Turkle, whose own psychoanalysis is performed by more conventional American analysts in the vicinity of Boston (see the book for further details), is befriended by Lacan. This is because Lacan wants her to write nice things about him. He is didactic, non enigmatic amid his enigmatic ciphers. Jacques is nice to her. I am telling you – you can’t make this stuff up. Turkle is perhaps the only – how shall I put it delicately – attractive woman academic that he does not try to seduce.

Lacan “gets it” – even amid his own flawed empathy – you don’t mess with this one. Yet Lacan’s trip to Boston – Harvard and MIT – ends in disaster. This has nothing – okay, little – to do with Turkle – though her colleagues are snarky. The reason? Simple: Lacan can’t stop being Lacan. Turkle’s long and deep history of having to live with the “Zimmerman / Turkle” name of the father lie, hidden in plain view, leaves Turkle vulnerable in matters of the heart. She meets and is swept off her feet by Seymour Papert, named-chair professor at MIT, an innovator in computing technology and child psychology, the collaborator with Marvin Minsky, and author of Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. Seymour ends up being easy to dislike in spite of his authentic personal charm, near manic enthusiasm, interestingness, and cognitive pyrotechnics.

Warning signs include the surprising ways Sherry have to find out about his grown up daughter and second wife, who is actually the first one. Sherry is vulnerable to being lied to. The final straw is Seymour’s cohabitating with a woman in Paris over the summer, by this time married to Sherry. Game over; likewise, the marriage. To everyone’s credit, they remain friends. Sherry’s academic career features penetrating and innovative inquiries into how smart phone, networked devices, and screens – especially screens – affect our attention and conversations.

Turkle’s research methods are powerful: she talks to people, notes what they say, and tries to understand their relationships with one another and with evocative objects, the latter not exactly Winnicott’s transitional objects, but perhaps close enough for purposes of a short review. The reader can imagine her technology mesmerized colleagues at MIT not being thrilled by her critique of the less than humanizing aspects of all these interruptions, eruptions, and corruptions of and to our attention and ability to be fully present with other human beings.

After a struggle, finding a diplomatic way of speaking truth to power, Turkle gets her tenured professorship, reversing an initial denial (something that rarely happens). The denouement is complete. The finalè is at hand.

Sherry hires a private detective and reestablishes contact with her biological father, Charles. His “experiments” on Sherry that caused her mother to end the marriage, indeed flee from it, turn out to be an extreme version of the “blank face” attachment exercises pioneered by Mary Main, Mary Ainsworth and colleagues, based on John Bowlby’s attachment theory. The key word here is: extreme.

I speculate that Charles was apparently also influenced by Harry Harlow’s “love studies” with rhesus monkeys, subjecting them to extreme maternal deprivation (and this is not in Turkle). It didn’t do the monkeys a lot of good, taking down their capacity to love, attachment, much less the ability to be empathic (a term noticeably missing from Harlow), leaving them, autistic, like emotional hulks, preferring clinging to surrogate cloth mothers to food. Not pretty.

In short, Sherry’s mother comes home unexpectedly to find Sherry (of tender age) crying her eyes out in distress, all alone, with Charles in the next room. Charles offers mom co-authorship of the article to be published, confirming that he really doesn’t get it. Game over; likewise, the marriage.

On a personal note, I was engaged by Turkle’s account of her time at the University of Chicago. Scene change. She is sitting there in lecture room Social Science 122, which I myself frequented. Bruno Bettelheim comes in, puts a straight back chair in the middle of the low stage, and delivers a stimulating lecture without notes, debating controversial questions with students, who were practicing speaking truth to power. It is a tad like batting practice – the student throws a fast ball, the Professor gives it a good whack. Whether the reply was a home run or a foul ball continues to be debated. I was in the same lecture, same Professor B, about two years later. Likewise with Professors Victor Turner, David Grene, and Saul Bellow of the Committee on Social Thought.

On a personal note, my own mentors were Paul Ricoeur (Philosophy and Divinity) and Stephen Toulmin, who joined the Committee and Philosophy shortly after Turkle returned to MIT. Full discourse: my dissertation on Empathy and Interpretation was in the philosophy department, but most of my friends were studying with the Committee, who organized the best parties. I never took Bellow’s class on the novel – my loss – because it was reported that he said it rotted his mind to read student term papers; and I took that to mean he did not read them. But perhaps Bellow actually read them, making the sacrifice. We will never know for certain.

One thing we do know for sure is that empathy is no rumor in the work of Sherry Turkle. Empathy lives in her contribution.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD, and the Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy: Capitalist Tool (Part 3): Let’s do the numbers

Listen to this post on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/6nngUdemxAnCd2B2wfw6Q6

Empathy by the numbers

I have been known to say: “We don’t need more data; we need expanded empathy.” But truth be told, we need both.

In an April/May survey by the human resources company Businessolver of some 1,740 employees, including 140 CEOs and some 100 Human Resources (HR) professionals, respondents reported:

37% of employees believe that empathy is highly valued by their organizations and is demonstrated in what they do.

Of the other 63% of employees, nearly one in three employees believe their organization does not care about employees (29%).

One in 3 believe profit is all that matters to their organization (31%).

Nearly one in two believe their organization places higher value on traits other than empathy (48%).

The evidence supports a conclusion that a significant deficit exists between experience and expectations relating to empathy. On a positive note, 46% of employees believe that empathy should start at the top. This opens the way for business leaders to articulate the value of expanding business results through empathy. The same survey indicates that the three most important behaviors for employers to demonstrate empathy include:

listening to customer needs and feedback (80%);

having ethical business practices (78%);

treating employees well, including being concerned about their physical and mental well-being (83%).

Three behaviors that demonstrate empathy according to the Americans Businessolver Survey:

listening more than talking (79%);

being patient (71%);

making time to talk to you one-on-one (62%).

The five behaviors that demonstrate empathy in conversation include:

verbally acknowledging that you are listening (e.g. saying, “I understand”) (76%);

maintaining eye contact (72%);

showing emotion (70%);

asking questions (62%);

making physical contact appropriate for the situation (i.e. shaking hands) (62%).

All this is well and good. But is it good for business? The survey reports that 42% of the survey respondents say they have refused to buy products from organizations that are not empathetic; 42% of Americans say they have chosen to buy products from organizations that are empathetic; 40% of Americans say that they have recommended the company to a friend or colleague. The answer to “Is empathy good for business?” is “Yes it is!”

“Corporate empathy” is not a contradiction in terms

This section is inspired by Belinda Parmar’s article “corporate empathy is not an oxymoron.”[i] Belinda Parmar is one of those hard to define, engaging persons who are up to something. She is founder of the consultancy The Empathy Business. She is an executive, a self-branded “Lady Geek,” public thinker, woman entrepreneur evangelist, and business leader.

According to Parmar, her consultancy’s corporate Empathy Index is loosely based on the work of the celebrated neuropsychologist Simon Baron-Cohen’s account of empathy.[ii] Parmar states in the newly revised 2016 Empathy Index, “empathy” is defined as understanding our emotional impact on others and responding appropriately. How does one map this to the four dimensional definition in Figure 1 (see p. 41 above)?

This captures what our multi-dimensional definition of empathy has called “empathic interpretation.” Parmar’s definition also calls out both the aspects of “understanding” and “responding,” which nicely correspond to empathic understanding and responsiveness, respectively, but misses empathic receptivity. Thus, three out of four. Not bad. How these get applied is a point for additional discussion.

Parmar and company’s Empathy Index aims at measuring a company’s success in creating an empathic culture on the job. This is not just a spiritual exercise. Parmar reports that the top 10 companies in the 2015 Empathy Index increased in value more than twice as much as the bottom 10, and generated 50% more earnings according to market capitalization.[iii] Now that I have your attention, a few more details.

The Empathy Index reportedly decomposes empathy into three broad categories including customer, employee, and social media. These contain further distinctions such as ethics, leadership, company culture, brand perception, public messaging in social media, CEO approval rating from staff, ratio of women on boards, accounting infractions and scandals. Over a million qualitative comments on Twitter, Glassdoor, and Survation were classified and assessed as part of the process of ranking the companies. Impressive. There is also a “fudge factor.”

The Empathy Index used a panel selected from the World Economic Forum’s Young Global leaders, who were asked to rate the surveyed companies’ morality. Note that Belinda Parmar was herself one of these leaders at some point, though presumably not for purposes of her own survey. Further conditions and qualifications apply. The company must be publicly traded and have a market capitalization of at least a billion dollars. The companies were predominately companies in the US and UK, a few Indian and no Chinese (due to difficulty getting the data). All the companies on the index had large numbers of end-user consumers (see “The Most Empathetic Companies,” 2016, Harvard Business Review for further details on the methodology). [iv]

Presumably the absence of steel mill, oil service, and aero-space-defense companies is not a reflection on their empathy, but simply indicates the boundaries of the survey. The 2015 index is widely available publicly and will not be repeated here. Suffice to say that the top three companies in 2015 were LinkedIn, Microsoft, and Audi. Google was at 7; Amazon, 21; Unilever, 38; Uber, 59; Proctor & Gamble, 62; IBM Corp, 89; Twitter, 93; and 98, 99, and 100 were British Telecom Group, Ryanair, and Carphone Warehouse, respectively. Interesting. My sense is that being on the list at all and relative ranking on the list in comparison with companies in a similar industry is more important than any absolute value or the numeric score as such, though the absence of a intensely consumer-product-oriented company such as Nestlé does give one pause. It is a deeply cynical statement, but an accurate one, that you know the pioneers by the arrows in their backs.

The truth of this otherwise politically incorrect observation is that innovators do not get the product or service perfect the first time out, and competitors are strongly incented to criticize and try to improve on the original breakthrough. Therefore, I acknowledge the value of the Empathy Index, and I acknowledge Belinda Parmar’s contribution. Empathy is no rumor in the work Parmar and her team is doing. Empathy lives in the work she and her team are doing.

How shall I put it delicately? The challenge is distinguishing empathy from ethics, niceness, generosity, compassion, altruism, social responsibility, carbon footprint, education of girls (and boys), and a host of prosocial properties. As this list indicates, lots of things correlate with empathy. Lots of things are inversely correlated with empathy. Empathy is the source of the ten thousand distinctions in business, including correlation with improved revenue, and meanwhile empathy gets lost in the blender.

The Empathy Index is a brilliant idea—and I am green with envy in that I did not implement it. In a deep sense, the only thing missing in my life is that my name is not “Belinda Parmar.”

Yet the reduction to absurdity of corporate empathy progresses apace with the Empathy Index as carbon footprint, reputation on social media, and CEO approval rating get included.

This index was designed prior to the revelation that social networking systems had become a platform for a foreign power (Russia) to publish exaggerated, controversial positions designed to ferment social conflict over race, economics, and extremist politics in the USA. Presumably further checks and balances are needed prior to accepting the reputations culled from such networks, unless one wants to include the approval rating of Russian trolls. Nothing wrong with approval ratings as such, but I struggle to connect the dots with empathy. Empathy is now a popularity contest to drive reputation and, well, popularity.

An alternative perspective on corporate empathy

I acknowledge the engaging and powerful work being done by Belinda Parmer and associates to expand empathy in the corporate jungle. The challenges of engaging with empathy as a property of the complex system called a “corporation” should not be underestimated. However, I propose to elaborate an alternative point of view regarding corporate empathy.

Corporations are supposed to be treated as individuals under law, which makes sense if one restricts the context to having a single point of responsibility for the consequences of the corporation’s actions.

Thus, for example, the accounting department cannot say, “It’s not our fault; marketing made promises we were unable to honor while manufacturing cooked the books behind our back.” That is not going to work as an excuse. Whoever did it, the corporation is responsible. However, empathy in a corporate context is not additive in this way.

The empathy of the corporation is not the sum of the empathy of all the individuals. It is true that a single individual who becomes known as “unempathic” has the potential to “zero out” the empathy of the entire organization; but for empathic purposes, “corporate empathy” is the integral of the seemingly uncountable possibilities, interpretations, and responses of leaders, workers, stake-holders, across all the functions in the organization.

For example, when IBM says “everyone sells,” IBM does not mean that the geek in the software laboratory has a sales quota. That would be absurd. IBM means precisely that the geek in the lab sells by writing software code so great that it causes customers actually to call up the account (sales) representative and ask for it by name. This puts me in mind of Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction saying: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Likewise, with empathy: the customer may not directly experience the empathy of the geek in the back office, but the commitment, functionality, and teamwork “back there” is so over-the-top, that the sales person’s empathy with the customer is empowered in ways that seem magical.

In this alternative perspective, a corporation is an individual that positions itself on the continuum between “empathy in abundance” and “empathy is missing” by enacting four practices: (1) listening (2) relating as a possibility (3) talking the other person’s perspective (4) demonstrating all of these—listening, relating as a possibility, and walking in the other’s shoes—such that the other person (customer, employee, stake-holder, general public) is given back the person’s own experience in relating to the corporation in a way that the person recognizes as the person’s own.

It has been awhile since the mantra of empathic receptivity, understanding, interpretation and response has been reiterated, so the reader is hereby reminded to check on Figures 1 and 3 in the previous chapters for a review as needed (see pp. 41, 89). Empathy is not something “owned” by the executive suite, marketing, human resources, or sales, to the exclusion of other roles. Everyone practices empathy.

Stake-holders may include the general public, whose well-being and livelihoods are impacted by corporate practices (or lack thereof). For example, the general public was profoundly affected (and not just by the price of gasoline) by the failure of an off-shore oil well in 2010 that sent some 205.8 million gallons of crude oil pollution into the Gulf of Mexico.

It is never good news when one’s corporate break down becomes a major motion picture—in particular, a disaster movie such as Deep Water Horizon. Note also this implies that empathy is not a method of waging a popularity campaign on social media.

If the corporation is British Petroleum (BP), then the empathic response might well be an acknowledgment that your experience of us is: “The only thing more foul than our reputation is the pollution perpetrated on the coastlines of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida and the lives and livelihoods of the millions of people who live there.” And BP has to do this even while defending itself in court against major legal actions where anything one says can and will be used against you.

What does it mean for a corporation to listen? Ultimately customers, employees, stake-holders must decide if a corporation has been listening by the way the company’s representatives respond. At the corporate level, empathic receptivity (listening) and empathic responsiveness are directly linked.

“Empathically” means respond in such a way that boundaries between persons are respected and respectfully crossed, agreements with the other person (or community) are honored, the other is treated with dignity, the other’s point of view is acknowledged, and the other is responded to in such a way that the other person would agree, even if grudgingly, that its perspective had been “gotten.”

People test whether others have been listening by examining and validating their responsiveness. Responsiveness includes the questions that they ask and the comments that they make in response. Most importantly it includes follow up and follow through actions.

Once again, breakdowns point the way to breakthroughs. A less dramatic example than Deep Water Horizon? From a customer perspective, here is an example of an everyday breakdown: “Corporations to customers: Stop Calling! Go to the web instead. Fill out the form, and wait for a response”—usually in an undefined time. The experience is one of being left hanging.

Today many corporations prefer that the customer interact with them through their web site, because web sites are less expensive than call centers. Phone numbers are disappearing from web sites; and even when a phone number is present, it may not be the proper one. The phone number at the bottom of a press release causes the phone to ring in the marketing department, not customer service.

Even when a phone number is available, the wait time is long and the service representative, who is a fine human being, is poorly informed. What is the experience? No one is listening. That is not a clearing for success in building an empathic relationship.

What then is? An ability to assess quickly what is the break down, suggest a resolution, and have a defined process of escalation to open an inquiry into the problem. The breakthrough is when the customer call is acknowledged and the equivalent of the help desk trouble-shooter calls the customer back at the number provided to the automated system with the solution or proposed action. The technology to do this has existed ever since the call center was invented, but until Apple thought of it, no one configured it to work from outbound call center to customer.

From an employee perspective, an employee will experience the corporation as listening if the person who sets his or her assignments (“supervisor”) is a listener. That means creating a context in which a conversation between two human beings, who are both physically present, can occur. Given that one person may report to someone in a different city, teleconferencing has a great future as does a periodic in-person visit.

However, if the one person is multi-tasking, working on email while supposedly having a conversation with the other person, that is not listening. Eliminate distractions. Set aside emails. If one is awaiting an urgent update regarding an authentic emergency, then it is best to call that out at the start of the conversation. “I might have to interrupt to take a call from Peoria, where the processing plant has an emergency.”

An “open door” policy can mean different things, but I take it to mean that “anyone can talk to anyone” and not have to feel threatened with retaliation. An “open door” is a metaphor for “listen” or “be empathic.”

If an employee is having trouble focusing on the job, something is troubling her or him, and the listener demonstrates empathy by asking a relevant question or providing guidance that brings the trouble into the conversation: “Say more about that” or “Help me understand” can work wonders. As soon as the employee believes that someone is really listening, out come the details needed to engage in problem solving.

If we are engaging with what might be described as employee “personal issues” such as the ongoing need to care for a disabled parent or child, substance abuse, mental illness, corporations realize that managers are not therapists. Smart corporations marshal external resources that operate confidential crisis phone lines and referral services. It is not entirely clear what “confidential” means here, since if the employee is missing most people notice it; but presumably such an absence does not directly feed into the employee review process. Such personal assistance centers are able to make referrals to providers of medical, mental health, or legal services. The benefit for the corporation is that employee stress and distraction are reduced. The employee is able to continue contributing productively as an employee. It is an all around win-win.

Yet the employee and his crisis are predictably going to show up in the manager’s office at the end of the business day before a holiday weekend. This is perhaps the ultimate test of the manager’s empathy. He or she is now being addressed as a fellow human being by another human, all-too-human, human being.

This is an empathy test if there ever was one; and this is where practice and training can prepare the manager to respond appropriately by marshaling resources on short notice. In a crisis on Friday afternoon at 4 pm before a holiday weekend, managers can create loyalty for life in the commitment of the employee, who was assisted in a way that made a profound difference. “Above and beyond” recognition awards for the empathically responding manager are appropriate too.

Let us shift gears and take the conversation about corporate empathy up a level with a particular example. Nestlé has a portfolio of popular and even beloved brands that literally come tumbling out of the consumer’s pantry and refrigerator when one opens the door. Some 97% of US households purchase a Nestlé product, which extend from chocolate to beverages to prepared foods to baby food to frozen treats to pet products and beyond. You might not even know it, but Perrier, Lean Cuisine, Gerber, and Häagen Dazs are Nestlé brands. So are Purina pet products..

Nestlé is so committed to sustainability in nutrition, health, and wellness that it produces a separate annual report dedicated to identifying, measuring, and reporting on its progress against literally dozens of sustainability goals. After reviewing this material, as I did, the reader can hardly imagine that Nestlé has any commitments other than social responsibility, though Nestlé is a for profit enterprise and doing very well as one.

Sometimes our strengths are also our weaknesses. Nestlé is a strong contender to be the most empathic corporation on the planet, regardless of how one chooses to define empathy. Yet it did not even get on Belinda Parmar’s Empathy Index. What gives? A single blind spot in the 1970s, in which Nestlé leadership thought it saw a long term growth opportunity in infant (baby) formula, got in the way. Given the population growth in parts of Asia and Africa, Nestlé thought it could steal a march on the competition.

Nestlé had been a force in infant formula, especially for those babies whose mothers are unable to nurse due to illness or when it comes time to wean the infant. Yet it looks like corporate planners projected first world infrastructure onto the third world in an apparent breakdown in empathic understanding and interpretation. A world of good work and good will was destroyed or at least put at extreme risk.

Nestlé’s marketing of baby formula has created an enduring controversy. Starting in the 1970s Nestlé has been the target of a boycott based on the way that Nestlé marketed baby formula in the developing world.[i] From a public relations perspective, it has been a breakdown, if not a train wreck. The initial issue was supposedly that Nestlé was too aggressive in marketing baby formulation as a substitute for breast feeding. However, when one looks at the details, the issue really seems to be empathizing with the practice of breast feeding, given life in many third world countries. A breakdown in empathy?

The third world often lacks clean water, reliable power for sterilization of baby bottles, instruction labels in local languages that can be read and understood and followed by possibly illiterate or partially literate mothers. If the mother is healthy and lactating, breast feeding is a strong candidate to be the preferred method of infant feeding.

I have been known to say: “We don’t need more data, we need expanded empathy.” But, truth be told, both are required here.

Infant morbidity and mortality is reportedly three to six times greater for those infants using formula than for those who are breast fed.[ii]Nestlé responds—with a stance whose empathy is questionable—with a defensive conversation about compliance. Nestlé states that it fully complies with the 34th World Health Assembly code for marketing infant formula.

Nestlé’s Annual Review 2016 states with expanded empathy: