Home » compassion fatigue

Category Archives: compassion fatigue

How I changed my relationship with pain

Expanded power over pain is a significant result that may usefully be embraced by all human beings who experience pain – which describes just about everyone at some time or another. Acute pain communicates an urgent need for intervention; chronic pain is demoralizing and potentially life changing. Intervention required!

People who do not experience standard amounts of pain are at risk of hurting themselves. Dr. James Cox, senior lecturer at the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research at University College London, notes, “Pain is an essential warning system to protect you from damaging and life-threatening events” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat2019)). Admittedly not experiencing pain is a rare and concerning condition from which few of us suffer. Hence the practical approach considered here for the rest of humanity.

I changed my relationship to pain by working on the relationship. The result is that less pain occurs in my life and the pain that I do experience does not dominate my life. If one is completely pain-free, one is probably dead, which has different issues.

The following behaviors made a difference. Regular exercise, healthy diet, spiritual discipline (I have trained extensively in Tai Chi, but Yoga and/or meditation encompass the same results), consultations with professionals of one’s choice including medical doctors; and, here is the wild card, the purpose of this post: education in the different types of pain, including but not limited to acute pain versus chronic pain. The reader may say, “Holy cow! That’s too much work!” However, if the reader is in enough pain, then consider the possibility. What’s the alternative? Continue to suffer? Medically assisted suicide (where legal)? Opioids? The latter in particular have a place in hospice (end of life scenarios), in the week after surgery, but otherwise they are a deal with the devil. And, in any deal with the devil, be sure to read the fine print. “At a time when about 130 American die daily from opioid overdoses, scientists and drug companies are actively pursuing alternative non-opioid medications for acute and chronic pain” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat 2019)).

An example will be useful. I changed my relationship to pain, following my MDs guidance, by taking a double dose of NSAIDs – non steroidal anti-inflammatory “pain killers”. The idea is to “kill” the pain without killing the patient. This is no joke because NSAIDs such as Aleve can damage the mucous membranes of the gastro intestinal track (e.g., stomach), leading to ulcer-like conditions and the accompanying risks (not detailed here), which is why, even though they are over-the-counter, consultation with a medical doctor is important.

Doing Tai Chi changed my relationship to pain. Your mileage may vary, but I started to see results after ten weeks of dedicated daily work. My Tai Chi training has continued with one lengthy interruption for six years. My experience was the practice moved the pain threshold up. That is, I did not experience pain as acutely and when I did experience pain, it did not bother me as much. This can be a double-edged consideration. For example, the Tai Chi exercise of “holding the ball” is a stress position. One really needs a picture to see what this is.

One stands there with one’s arms encompassing a large ball at about the level of one’s chest with one’s hips tucked slightly as if sitting back. One’s whole body is engaged and conditioned. After about ten minutes one starts to heat up and after about fifteen minutes one starts to sweat. This is Tai Chi, not Yoga, but Mircea Eliade discusses similar stress positions that generate Shamanic Heat (Eliade, (1964), Shamanism, translated Willard Trask. Princeton University Press (Bollingen)).

Now a word of caution regarding the pain threshold. I went for a dermatological treatment and I got burned, literally, (fortunately, not too seriously), because I did not say “Stop – it hurts!” Granted that most people want to experience less pain, it is important to not extinguish pain completely, because pain in its acute presentation is trying to tell one something – in this case, injury to one’s skin due to heat.

Here is another example. A colleague has an inflamed ankle. It throbs. It hurts. It is not fractured but imaging shows it is enflamed, stressed out. The thing is that this is not just the person’s sprained ankle – it is his whole life. Since he needs to lose weight, he needs to get exercise. Because he cannot get sufficient exercise, he cannot lose weight. The extra weight contributes to the ankle continuing to be stressed. Double-bind! Rock and the hard place. How is this individual going to break out of this tight loop? Now I know this is going to sound crazy, but here it is: Follow doctor’s orders! Go to the physical therapy! If you have got to wear “the boot” for a couple of weeks, do so. Start low (with the number of repetitions of exercises) – go slow. If the person had access to a swimming pool, that would be ideal, but that might not be workable for many people. SPA-like treatments, soaks in Epsom salts in sensory deprivation pods have value.

Many parallel examples can be cited in which a person knows exactly what she has to do (don’t even worry about the doctor) – why is the person not doing it? Many reasons exist, but one of them is that suffering becomes a comfort zone. Suffering is sticky. “Yes, I am miserable,” the individual says, but it is a familiar misery. Suffering has become an uncomfortable comfort zone. What would it take to give that up? Once one realizes, “This is what crazy looks like,” it becomes easier to give up the suffering. This is not a deep dive into the psychology of the unconscious, yet this is not merely a physical challenge. Yes, the ankle hurts – objectively, there is even an image that shows inflammation, albeit hazy and faint. However, even if there weren’t evidence of an injury – and soft tissue damage often escapes imaging, the emotional issue – ambivalence about one’s body image (“weight”) – gets entangled with the person’s whole life. In this case, a struggle with unhealthy excess weight – and the person’s emotions run with the ball – elaborate the injury psychologically. This is also a form of catastrophizing or awfulizing (made famous by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)), but CBT did not invent it.

I gave the example of an inflamed ankle, but it might also apply to lower back pain, headaches, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which are notoriously difficult to diagnose medically. Speaking personally, I want a quick fix. We all do. However, after a while, if the “fix” does not occur, there is no in principle limit on the amount of time and effort one can spend trying to find a quick fix. After a certain time, one gets a sense that one might put the time and effort into incremental progress – finding whatever moves the dial – whatever shifts the stuckness. Here’s what I did not want to hear: This is gonna take some work. After a time, one decides to roll up the sleeves and do the hard work need to get one’s power back. Healthy diet and a well-defined exercise program are important components. Finding an MD and/or health care provider including physical therapist where the interpersonal chemistry works is on the critical path to dialing down the suffering. Here “interpersonal chemistry” is another description for empathy. Look for someone whose empathy is open enough to encompass one’s pain and suffering without being coopted by it. This is the critical path to recovery.

The distinction between acute pain and chronic pain needs to be better understood by the average citizen. An excerpt from Neurology 101 may be useful. In acute pain, the peripheral nervous system in the body’s appendages such as one’s toes reports via neural connections to the central nervous system (e.g., the brain in one’s head). The impact of a heavy object such as a large brick with my toe releases neurotransmitters at the nociceptors (we are not talking Greek and “nocio” means “pain”). The mechanics are such that a message is delivered from the periphery to the center that what is in effect a boundary violation – an injury – has occurred. The brain then tells the toe to hurt – “Ouch!” The message is delivered seamlessly to the conscious person to whom the toe “belongs” in the neural map that associates the body with conscious experience unfolding in the person’s awareness. The toe which had quietly been doing its job in helping the person walk, balance, be mobile now makes a lot of “noise” – it starts throbbing. This is what acute pain feels like.

With chronic pain the scenario gets complicated. If the injury is subjected to other stressors, slow to heal, reinjured, or otherwise neglected, then the pain may continue across a period of days or weeks and become habitual. In effect, the pain signal becomes a bad habit. The pain takes on a life of its own. What does that even mean? What starts out as a way of reminding the person to attend to the injury gets stuck on “repeat”. Like the marketing company that keeps sending your notices even after you specify “Do not solicit!” The messaging is not just from the toe to the brain, from the periphery to the center, but it gets reversed. The messaging is from the center to the periphery, from the brain to the body part. The brain tells the periphery to hurt. Chronic pain becomes a source of suffering. Here “suffering” expands to include worry that anticipates and/or expects pain, which gets further reinforced when the pain actually shows up.

The poster child for chronic pain is phantom limb pain. Not all pains are created equal. Phantom limb pain provides compelling evidence that pain is “in one’s head” only in the sense that pain is in the brain and the brain is in one’s head. Only in that limited sense is pain in one’s head. Yet the pain is not imaginary. Documented as early as the American Civil War by Silas Weir Mitchell, individuals who had undergone amputation, felt the nonexistent, missing limb to itch or cramp or hurt. The individuals experienced the nonexistent tendons and muscles of the missing limb as cramping and even awakening the person from the most profound sleep due to pain (As noted, further in Haider Warraich. (2023). The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain. New York: Basic Books, pp. 110 – 111).

Fast forward to modern times and Ron Melzack’s gate control theory of pain marshals such phantom limb pain as compelling evidence that the nervous system contains a map of the body and the body’s pains point, which map has not yet been updated to reflect the absence of the lost limb. In effect, the brain is telling the individual that his limb is hurting using an obsolete map of the body – the memory of pain. Thus, the pain is in one’s head, but not in the sense that the pain is unreal or merely imaginary. The pain is real – as real as the brain that is indeed in one’s head and signaling (“telling”) one that one is in pain. (R. Melzack, (1974), The Puzzle of Pain. Basic Books.)

Whatever the level of pain, stress is probably going to make it feel worse. Therefore, stress reduction methods such as meditation, Tai Chi, Yoga, time spent soaking in a sensory deprivation pod, and SPA-like stress reduction methods are going to be beneficial in moving the pain dial downward.

One question that has not even occurred to scientists is whether it is possible to have the functional equivalent of phantom limb pain, even though the person still has the limb functionally attached to the body. This sounds counter-intuitive, but think about it. If there is a map of the body’s pain points in the central nervous system (the brain), there is nothing that says “phantom” pains cannot occur even if an appendage still exists. For example, the high school football player who needs the football scholarship to go to college because he is weak academically; he is not good at baseball, but actually hates football. He incurs a soft tissue sports injury, which gets elaborated due to emotional conflict about his ambivalent relationship with football, leaving him on crutches for far-too-long and both physically and symbolically unable to move forward in his life. As if the only three life choices are football, baseball, and academics?! Note that the description of the injury “painful soft tissue” already opens and shuts approaches to treatment. That is the devilish thing – what is the actual and accurate description? Thus, due to the inherent delays in neuroplasticity – the update to the brain’s map of the body is not instantaneous and one does not have new experiences with a nonexistent limb – pain takes on a life of its own.

Though an oversimplification, the messaging between the peripheral and central nervous systems is reversed. Instead of the peripheral limb telling the brain of a “hurt,” the brain develops a “bad habit” of signaling pain and tells the limb to hurt. That is the experience of chronic pain – pain has a life of its own – pain becomes the dis-ease (literally), not the symptom. What then is the treatment, doctor? Physical therapy (PT) – exercises to strengthen the knee and, in effect, teach him to walk again.

Chronic pain is discouraging, demoralizing, fatiguing, exhausting, negatively impacting one’s mental status. I have been cagey about my own experience of pain in this post, but it is a matter of record that I have osteoarthritis, a progressive deterioration of the cartilage in joints such as occurs in people who are getting older and who are long term runners. The person understandably and properly continuously asks himself – what am I experiencing? And does it include pain? No one is saying the “cure” is don’t think about it (pain), don’t worry about it. No one is saying “play hurt”? “Playing hurt” is a bad idea for so many reasons, including one is going to make a bad injury worse. Professional athletes who “play hurt” may indeed get a bunch of money, but they also often dramatically shorten their careers – and that costs them money.

While distraction from one’s pain can be useful in the short term, it is not a sustainable solution. Rather when, after medical determination of the sources of pain are determined to be unable to be completely extinguished or eliminated, one is saying undertake an inquiry into what one is really experiencing. Rather than react to the uncomfortable twinges and twitches, bumps and thumps, prodding and pokes, that one encounters, ask what one is really feeling. Undertake an inquiry into what one is experiencing. If, upon consideration, the answer is “The pain is acute going from 4 to 8 to 9 on the 10 point scale,” then stop and call for backup, including taking pain killers such as NSAIDS as recommended by an MD.

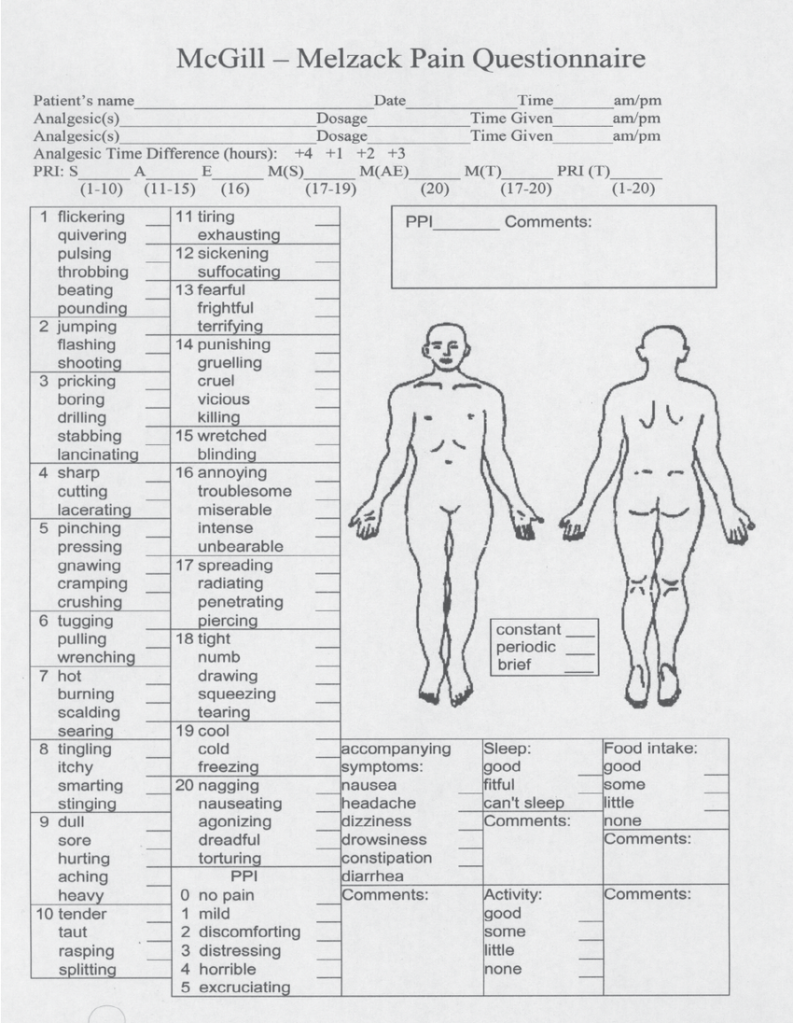

Here the vocabulary of pain is relevant. See Melzack’s McGill pain chart. [List the vocabulary]

Further background information will be useful. Haider Warraich, MD, in The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain (Basic Books, 2023) radicalizes the issue of pain that takes on a life of its own before suggesting a solution. After providing a short history of opium and morphine and opioids, culminating “in the most prestigious medical school on earth, from the best teachers and physicians, we [medical students] were unknowingly taught meticulously designed lies” (p. 185), that is, prescribe opioids for chronic pain. The reader wonders, where do we go from here? To be sure opioids have a role in hospice care and the week after surgery, but one thing is for certain, the way forward does not consist in prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

After reviewing numerous approaches to integrated pain management extending from cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to valium, cannabis and Ketamine – and calling out hypnosis (hypnotherapy) as a greatly undervalued approach (no external chemicals are required, but the issue of susceptibility to hypnotic suggestibility is fraught) – Dr Warraich recovers from his own life changing back injury in a truly “physician heal thyself” moment thanks to dedicated PT, physical therapy (p. 238). If this seems stunningly anti-climactic, it is boring enough to have the ring of truth earned in the college of hard knocks, but it is a personal solution (and I do so like a happy ending!), not the resolution of the double bind in which the entire medical profession finds itself (pp. 188 – 189). The way forward for the community as a whole requires a different, though modest, proposal. The patient signs up for and completes physical therapy (PT), a custom set of exercises tailed to his pain condition and mobility issues.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “The body is the best picture of the soul.” The default since René Descartes is to distinguish physical pain from psychic pain – what used to be called the difference between “body” and “soul” before science “proved” that the soul did not exist. (Once again, we are talking Greek “psyche” is the Greek word for “souI.”) Nevertheless, in spite of the “proof” that the soul does not exist, soul-like phenomena keep showing up. For example, if the person’s “soul” is regularly subjected to negative verbal feedback from those in authority, the person becomes physically ill – ulcers, headaches, lower back pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). As noted, these are notoriously difficult to diagnoses. The adverse childhood experience survey (ACE) provides solid evidence that psychic and moral injuries correlate significantly with major medical disorders (e.g., Felitti 2002).

One big issue is that we (science and scientists) lack a coherent, effective account of emergent properties. One with neurons. The alternative is the current reductive paradigm according to which, in spite of contrary assertions, on has trouble explaining that things really are what they seem to be – that table are tables andmade of microscopic components such as atoms. We start with neurons. We are neurons “all the way down.” Neurons generate stimuli; stimuli generate sensations/experiences; experiences generate [are] responses; responses form patterns; patterns generate meaning; meaning generates language. With the emergence of language, things really start to get interesting. Organized life reaches “take off” speed. Language generates community; community generates – or rather is functionally equivalent to – culture, art, poetry, science, technology, and the world as we know it.

What about individuals who are put in a double-bind by circumstances as when someone in authority makes a seemingly impossible demand? For example, the army Sargent gives what seems to be a valid military order to the corporeal to shoot at the rapidly approaching auto, thinking it is a suicide car bomb, but it is really an innocent family. The soldier, thinking the order is valid and that he is protecting his team, follows the order. The solider is now both a perpetrator and a survivor. People have gotten hurt who ought not to have been hurt. Moral inquiry. Moral trauma has occurred. Tai Chi is not going to save this guy. This take the form of guilt – which is aggression – hostile feeling and anger – turned against one self. The individual’s agency – the individual’s power as an agent to choose – is compromised by contingent circumstance, including the individual’s unavoidable choice in the circumstance, since taking no action is also a choice.

This is why the ancient Greeks invented tragedy. A careful reading of the Greek tragedies, which cannot be adequately canvassed here, shows that virtually every tragic hero has the compromised agency characteristic of a double bind. Oedipus is a powerful agent, yet compromised and brought low by inadequate information. Information asymmetries! Antigone’s agency is bound, doubly, by the conflict between the imperatives of politics and the integrity of family. Agamemnon’s agency is compromised by the negative aspect of honor and pride and an overweening narcissism. Iphigenia’s agency is compromised by literally being bound and gagged (admittedly a limit case). Double-binds have also been hypothesized to contribute to the causation of major mental illness (Bateson 1956). Contradictory messages from parents, explicit versus implicit, spoken versus unspoken, are particularly challenging. Here the fan out to related issues is substantial.

I changed my relationship to pain and suffering by reading all thirty existing Greek tragedies. One might say if something is worth doing, it is worth over-doing, and the reader might try starting with just one. Examples of pain and suffering occur in abundance: acute pain – Hercules puts on the poisoned cloak, which burns his flesh; chronic pain – Philoctetes has a wound that will not heal and throbs periodically with painful sensations; and suffering – Oedipus is misinformed about who is his birth mother and after having children with her he suffers so from his awareness of his violation of family standards that he mutilates himself, tearing his eyes out. The latter would, of course, be acute pain, but the cause, the trigger, is thinking about what he has done in relation to the expectations of the community, namely, violating the incest taboo.

Now, according to Aristotle, the representation of such catastrophes is supposed to evoke pity and fear in the audience (viewer) of the classic theatrical spectacle. Indeed, such spectacles – even though the violence usually happens “off stage” and is reported – are not for the faint of heart. We seem to want to identify with the characters in a narrative, which, in turn, activates our openness to their experiences in an entry level empathy that communicates a vicarious experience of the character’s struggle and suffering. Advanced empathy also gets engaged in the form of appreciation of who is the character as a possibility in relation to which the viewer (audience) considers what is possible in her of his own life. One takes a walk in the other’s shoes, after having taken off one’s own. Other examples of similar experiences include why (some) people like to see horror movies. One does not run screaming from the theatre, but conventionally appreciates that the experience is a vicarious one – an “as if” or pretend experience. Likewise, with “tear jerker” style movies – one gets a “good cry,” which has the effect of an emotional purging or cleansing.

Now I am not a natural empath, and I have had to work at expanding my empathy. In contrast, the natural empath is predisposed, whether by biology or upbringing (or both), to take on the pain and suffering of the world. Not surprisingly this results in compassion fatigue and burn out. The person distances him- or herself from others and displays aspects of hard-heartedness, whereas they are actually kind and generous but unable to access these “better angles.” It should be noted that empathy opens one up to positive emotions, too – joy and high spirits and gratitude and satisfaction – but, predictably, the negative ones get a lot of attention.

“Suffering” is the kind of thing where what one thinks and feels does make a difference. Now no one is saying that Oedipus should have been casual about his transgressions – “blown it off” (so to speak); and the enactment does have a dramatic point – Oedipus finally begins to “see” into his blind spot as he loses his sight. Really it would be hard to know what to say. Still, the voice of reality would council alternatives – other ways are available of making amends – making reparations – perhaps more than two “Our Fathers” and two “Hail Marys” as penance – what about community service or fasting? “Suffering” is not just a conversation one has with oneself about future expectations. It is also a conversation one has with oneself about one’s own inadequacies and deficiencies (whether one is inadequate or not). For example, unkind words from another are hurtful. In such cases what kind of “pain” is the hurt? We get a clue from the process of trying to manage such a hurt. The process consists in setting boundaries, setting limits, not taking the words personally (even though inevitably we do). The hurt lives in language and so does the response. Therefore, in an alternative scenario, one takes the bad language in and turns it against oneself. One anticipates a negative outcome. One gets guilt (once again, regardless of whether one has does something wrong or not).

The coaching? If you are suffering from compassion fatigue, then dial down the compassion. This does not mean become hard-hearted or mean. Far from it. This means do not confuse a vicarious experience of pain and suffering with jumping head over heels into the trauma itself. What may usefully be appreciated is that practices such as empathy, compassion, altruism are not “on off” switches. They are not all or nothing. Skilled executioners of these practices are able to expand and contract their application to suit the circumstances. To be sure, that takes practice. The result is expanded power over vicariously shared pain and suffering. One gets power back and is able to assist the other in recovering their power too. (Further tips and techniques on how to change one’s thinking and expand one’s empathy are available in my Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide (with 24 full color illustrations by Alex Zonis), also available as an ebook.)

Before concluding, I remind the reader that “all the usual disclaimers.” This is a personal reflection. The only data is my own experience and bibliographical references that I found thought provoking. “Your mileage may vary.” If you are in pain (which, at another level and for many spiritual people, is one definition of the human condition) or if you are in the market for professional advice, start with your family doctor. If you do not have one, get one. Talk to a spiritual advisor of your own choice. Above all, “Don’t hurt yourself!” This is not to say that I am not a professional. I am. My PhD is in philosophy (UChicago) with a dissertation entitle Empathy and Interpretation. I have spent over 10K hours researching and working on empathy and how it makes a difference. So if you require expanded empathy, it makes sense to talk to me. A conversation for possibility about empathy can shift one’s relationship with pain.

Bibliography

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J., 1956, Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, Vol. 1, 251–264.

Corley, Jacquelyn. (2019). The Case of a Woman Who Feels Almost No Pain Leads Scientists to a New Gene Mutation. Scientific American. March 30, 2019. Reprinted with permission from STAT. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-case-of-a-woman-who-feels-almost-no-pain-leads-scientists-to-a-new-gene-mutation/

Eliade, Mircea. (1964). Shamanism. Princeton University Press (Bollingen).

Felitti VJ. (2002). The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead. The Permanente Journal (Perm J). 2002 Winter;6(1):44-47. doi: 10.7812/TPP/02.994. PMID: 30313011; PMCID: PMC6220625.

Melzack, R. (1974). The Puzzle of Pain. New York: Basic Books.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide is now an ebook – and the universe is winking at us in approval!

The release of the ebook version of Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide coincides with a major astronomical event – a total solar eclipse that traverses North America today, Monday April 8, 2024. The gods are watching and wink at us humans to encourage expanding our empathic humanism!

My colleagues and friends are telling me, “Louis, you are sooo 20th Century – no one is reading hard copy books anymore! Electronic publishing is the way to go.” Following my own guidance about empathy, I have heard you, dear reader. The electronic versions of all three books, Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide, Empathy Lessons, and A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy – drum roll please – are now available.

A lazy person’s guide to empathy guides you in –

- Performing a readiness assessment for empathy. Cleaning up your messes one relationship at a time.

- Defining empathy as a multi-dimensional process.

- Overcoming the Big Four empathy breakdowns.

- Applying introspection as the royal road to empathy.

- Identifying natural empaths who don’t get enough empathy – and getting the empathy you need.

- The one-minute empathy training.

- Compassion fatigue: A radical proposal to overcome it.

- Listening: Hearing what the other person is saying versus your opinion of what she is saying.

- Distinguishing what happened versus what you made it mean. Applying empathy to sooth anger and rage.

- Setting boundaries: Good fences (not walls!) make good neighbors: About boundaries. How and why empathy is good for one’s well-being. Empathy and humor.

- Empathy, capitalist tool.

- Empathy: A method of data gathering.

- Empathy: A dial, not an “on-off” switch.

- Assessing your empathy therapist. Experiencing a lack of empathic responsiveness? Get some empathy consulting from Dr Lou. Make the other person your empathy trainer.

- Applying empathy in every encounter with the other person – and just being with other people without anything else added. Empathy as the new love – so what was the old love?

Okay, I’ve read enough – I want to order the ebook from the author’s page: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Advertisements

https://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.7/html/safeframe.html

REPORT THIS AD

Practicing empathy includes finding your sense of balance, especially in relating to people. In a telling analogy, you cannot get a sense of balance in learning to ride a bike simply by reading the owner’s manual. Yes, strength is required, but if you get too tense, then you apply too much force in the wrong direction and you lose your balance. You have to keep a “light touch.” You cannot force an outcome. If you are one of those individuals who seem always to be trying harder when it comes to empathy, throttle back. Hit the pause button. Take a break. However, if you are not just lazy, but downright inert and numb in one’s emotions – and in that sense, e-motionless – then be advised: it is going to take something extra to expand your empathy. Zero effort is not the right amount. One has actually to practice and take some risks. Empathy is about balance: emotional balance, interpersonal balance and community balance.

Empathy training is all about practicing balance: You have to strive in a process of trial and error and try again to find the right balance. So “lazy person’s guide” is really trying to say “laid back person’s guide.” The “laziness” is not lack of energy, but well-regulated, focused energy, applied in balanced doses. The risk is that some people – and you know who you are – will actually get stressed out trying to be lazy. Cut that out! Just let it be.

The lazy person’s guide to empathy offers a bold idea: empathy is not an “off-off” switch, but a dial or tuner. The person going through the day on “automatic pilot” needs to “tune up” or “dial up” her or his empathy to expand relatedness and communication with other people and in the community. The natural empath – or persons experiencing compassion fatigue – may usefully “tune down” their empathy. But how does one do that?

The short answer is, “set firm boundaries.” Good fences (fences, not walls!) make good neighbors; but there is gate in the fence over which is inscribed the welcoming word “Empathy.”

The longer answer is: The training and guidance provided by this book – as well as the tips and techniques along the way – are precisely methods for adjusting empathy without turning it off and becoming hard-hearted or going overboard and melting down into an ineffective, emotional puddle. Empathy can break down, misfire, go off the rails in so many ways. Only after empathy breakdowns and misfirings of empathy have been worked out and ruled out – emotional contagion, conformity, projection, superficial agreement in words getting lost in translation – only then does the empathy “have legs”. Find out how to overcome the most common empathy breakdowns and break through to expanded empathy – and enriched humanity – in satisfying, fulfilling relationships in empathy.

Order from author’s page: Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Order from author’s page: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Read a review of the 1st edition of Empathy Lessons – note the list of the Top 30 Empathy Lessons is now (2024) expanded to the Top 40 Empathy Lessons: https://tinyurl.com/yvtwy2w6

Read a review of A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/49p6du8p

Order from author’s page: A Critical Review of Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/29rd53nt

Order from author’s page: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition: https://tinyurl.com/mfb4xf4f

Above: Cover art: Empathy Lessons, 2nd Edition, illustration by Alex Zonis

Advertisements

https://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.7/html/safeframe.html

REPORT THIS AD

Order from author’s page: A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy: https://tinyurl.com/mfb4xf4f

Above: Cover art: A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy, illustration by Alex Zonis

Finally, let me say a word on behalf of hard copy books – they too live and are handy to take to the beach where they can be read without the risk of sand getting into the hardware, screen glare, and your notes in the margin are easy to access. Is this a great country or what – your choice of pixels or paper!?!

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

A Rumor of Empathy in Brené Brown’s Atlas of the Heart (Reviewed)

Review: Brené Brown, (2021). Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience. New York: Random House, pp. 304.

This is three books in one. It is a psychology “how to” book filled with tips and techniques about how to identify and name emotions, feelings, affects, and their triggers and consequences. This inquiry is engaged in order to build connections and community. It works. People who are able to name their emotions and feeling experience expanded power in getting what they want and need from other people. They also get expanded power in contributing to building meaningful connections and community.

Second, the Atlas is a research report on what might be described as “crowd sourcing” (my term, not Brown’s) what emotions were important to some 66,625 persons in Brené Brown’s massive online classes in 2013/14.

Comments and narratives were solicited from the participants. This input was anonymized, color coded, aggregated, filtered, subjected to expert selection as to which emotions and emotion-related experiences were significant in promoting “healing.” The terms were then defined using 1500 academic publications. What falls out of this complex and interesting, though not entirely transparent process, are emotions, emotional triggers, emotional consequences, experiences, lots of experiences, and, well – an atlas of the heart. Readers are all the richer for it.

Finally, Atlas is an art book. The text on high quality paper is interspersed with color photos, cartoons, and enlarged quotations of key phrases such as one would find on social media. Take a tip or technique and using large and colorful type, put it on a page by itself: “I’m here to get it right, not to be right [p. 247. Note: there is no close quote. Is that a typo or poetic license?]

I especially liked the photos of Brown’s hand written journal (or college essay?), saying “throughout our lives we must experience emotions and feelings that are inevitably painful and devastating” (October 9, 1984). Early on, Brené showed promise, and she movingly shares her struggles and what she had to survive in her family of origin. The photo of the dog with the guilty, “hang dog” expression, next to the torn up upholstered chair was genuinely funny. Never let it be said that dogs don’t experience emotions! The artistic aspects will be deemphasized in this review, but the book definitely has possibilities for placement on the “coffee table” to invite browsing and conversation prompts.

The book succeeds in all three of its aspirations, though to different degrees.

At this point, an analogy may be useful. People are not born knowing the names of colors. Children applying to start kindergarten are quizzed on such basics as the names of the letters (ABCs), their address and phone number, and the names of the colors. The spectrum from red through orange, yellow, green, blue, to violet is indeed a marvelous thing. But no one assumes anyone knows what these distinctions are called without guidance. Why then is it that children (and of all ages) are assumed to know the difference between basic emotions fear, anger, sadness, high spirits, much less more subtle nuanced feelings such as envy, jealousy, resentment, shame, guilt, and so on?

This is the first challenge that Brené Brown addresses with her book. She provides a guide, an atlas of the heart, to people struggling to identify the emotions and emotion-ladened experiences they are feeling, sensing, or trying to express. Even though Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, and Mary Gordon’s Roots of Empathy, have taken decisive steps to put this aspect of emotional intelligence – x identifying and naming the emotions – on the school curriculum map, large numbers of people of all ages struggle with the basics. What is this feeling that I am feeling? What is this emotion, if it is an emotion, that I am experiencing?

Brown begins with a nod to the innovative body of work on the emotions by Paul Ekman (e.g., Emotions Revealed. New York: Owl (Henry Holt), 2003). Ekman put facial micro-expression on the map as the key to emotions with a seven year plus study resulting in his Facial Action Coding Scheme. According to Ekman, a relatively small set of some seven basic emotions are universal, evolutionarily based, and part of a biological affective program that is “hardwired” into our mammalian biology. These basic emotions (sadness, anger, agony, surprise, fear, disgust, contempt, and maybe enjoyment) get elaborated and transformed in a thousand ways by social conventions, community standards and cultural pretenses.

The human face is an emotional “hot spot,” according to Ekman. The micro-expressions are the “tells” that disclose a person’s underlying feeling or attitude, regardless of the facial expression the person may be adopting for social display purposes. Thus, a person may smile to express agreement with his friends, but his eyes do not participate in the smile (also called a “Duchenne smile”) and something looks not quite sincere. More concerning, the would-be suicide bomber puts on a calm, happy face, but a micro-expression of contempt momentarily steals across his face, expressing his hatred for the system he is about to try to destroy. Notwithstanding Ruth Ley’s penetrating and trenchant critique of loose ends in Ekman’s approach (see Ley, The Ascent of Affect. Chicago: University of Chicago press, 2017), his approach remains today the dominate design in emotion research. Enter Brené Brown’s contribution.

For example, Brown’s first constellation of emotions engaged include “stress, overwhelm, anxiety, worry, avoidance, excitement, dread, fear, vulnerability” (p. 2). She quotes the American Psychological Association Definition of anxiety (so we know where that definition came from!): “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increase blood pressure” (p. 9).

Worry and avoidance, not exactly emotions as such, are ways of dealing with the painful aspects of anxiety. Excitement seems to be the physiological aspects of anxiety given a positive spin, valence, or trajectory. Add “negative event approaching” and “present danger” and you’ve got dread and fear. Stress and overwhelm are the again physiological aspects of anxiety, elaborated, for example, by having to be a waitress in a restaurant at its busiest (as was Brown while working her way through college). “Stressed is being in the weeds; overwhelm is being blown.”

For Brown, vulnerability is a key emotion, since it initially shows up as a weakness to hide, but has the potential, when approached with a willingness to embrace risk, to be transformed into courage, accomplishment, and what people really want from inspirational speakers – inspiration. Never was it truer, our weaknesses are our strengths. Dialectically speaking.

At this point, I am inspired by Brown’s contribution, and will not split hairs over what is an emotion and what an emotional fellow traveler. Vulnerability is the perception and related belief, thought, or cognition, whether accurate or not, that the person is able to be hurt whether physically or in social status. Keep your friends close but your enemies, including your near enemies such as flatterers and people who ask you to lend them money, closer?

This is a good place to point out that if you really want to “get” the emotions, you may usefully engage with Brown. Definitely. But do not overlook Paul Griffiths, What Emotions Really Are (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997). Emotions may not even be a natural kind. A mammal (for example) is a natural kind, emotions arguably are not. Emotions are a “kludge” cobbled together by the scientific community from an evolutionary affective program, moral sentiments such as righteous indignation in the face of social injustice (a strategic, energetic, passionate reaction to enforce the social convention of promising among distrustful neighbor), and social pretence such as romantic love.

In a famous one line statement in Martin Heidegger’s magnum opus, Being and Time (1927: H139), he says that the study of the moods, affects, and emotions has not made a single advance since Book II of Aristotle’s Rhetoric (347? BCE). He then proposes that anxiety is the way the world is globally disclosed as a limited finite whole. It is tempting for purposes of being collegial to write, “Finally an advance on Aristotle, Brené!” but she would surely be the first to acknowledge that would indeed be a high bar. Suffice to say, Brown’s contribution is significant and in many ways, impressive. Aristotle is still Aristotle. (See Agosta 2010 in the References.)

Since this is not a softball review, and in spite of saying a lot of interesting things about love, it is not defined in Brown’s book. I applaud Brown’s decision to leave the definition of love to the poets and artists, whether intentionally or by omission. Anyone who tries to define love is likely to end up with more arrows in the back than Cupid has in his quiver.

A definition would be something like Freud’s statement: Love is aim-inhibited sexuality. Or Aristophanes narrative that love is the search for one’s other half and the joining with that half if/when one finds it. Or Bob Dylan’s “love is just a four letter word.” No inhibition here; just hormones all the way down.

The research challenge present here is how to finesse the canonical interpretation of the data by her team of experts, assembled from her extensive network of colleagues, which data after all is highly survey-like yet without controls, randomization, or rigorous sampling dynamics. The outer boundary of the demographic respondents seems to be the 66K plus followers who signed up for her massive online courses.

Other features of the book that became wearing for this reviewer were the seemingly endless rhetoric of stipulation, how inspiring to her has been everyone else’s research from which she liberally borrows, always with a slew of well-crafted footnotes, and an epidemic of near enemies to authenticity and courage. This is perhaps inevitable when one has to give 87 definitions.

Still, the question invites inquiry: Where after all did the definitions of these 87 emotions and experiences really come from? I cannot figure it out. My best guess is “the team” made it up based on reading 1500 research articles and extensive input from the “lead investigator,” Brené Brown. To be sure, Brown is generous with her recognition and acknowledgements of a long list of thinkers, mentors, scholars, spiritual guides, and researchers. She really lays it on thick with how much she has learned from her friends and colleagues; and it indeed must be thrilling to have one’s name called out by a celebrity academic. I am green with envy – not one of the positive emotions – that I am unlikely to make the short list with my seven books on empathy, especially given this review.

Still, Brown’s contribution is a strikingly original synthesis of existing ideas. I have been known to say, “Research also includes talking to people.” Yet the risk is scientism. The air of scientific authority without the fallibility of human subjectivity and idiosyncrasy. It may not matter. The value lies in the tips and techniques that can be used to build community and connection. If it is scientism, then it is scientism at its best.

Once again, since this is not a softball review, I join the debate about one of the most troubling of emotions, anger. Brown properly raises the issue of whether anger is fundamental or derivative. Anger often seems to be a front for something else = x, such as shame, guilt, jealousy, humiliation (this list is long). In spite of the dramatic display of being angry, there is something inauthentic about anger. Anger is a burden to those who experience it, and this burden often gets discharged in maladaptive and self-defeating ways by acting out aggression and violence. Brown’s position is a masterpiece of studied ambiguity. I agree.

My take on this? If you want to see or make people angry, then hurt their feelings. If you see an angry person, ask: Who hurt the person’s feelings and/or did not give the person the respect, dignity, or empathy that the person deserves or to which the person feels entitled. You see here the problem? Entitlement, legitimate or otherwise.

This was Heinz Kohut’s point: When people don’t get the empathy they need and deserve, they fragment emotionally – and one of the fragments is narcissistic rage (extreme anger). From this perspective, empathy is not a mere psychological mechanism but the foundation of community, connection and intersubjectivity. Donna Hicks makes the same point in Dignity (New Haven and London: Yale University press, 2011). If you see anger in the form of conflict, substitute the word “dignity” for “empathy” – someone has experienced a dignity violation, a breakdown, a loss of dignity, which loss must be restored to have any hope of resolving the conflict (whether in Northern Ireland or the bedroom).

As regards empathy, Brown engages it along with compassion, pity, sympathy, boundaries, and comparative suffering. Like many psychologists, Brown regards empathy as a psychological mechanism not empathy as a way of being and the foundation of community. For the latter, the foundation of community, like a good Buddhist, she privileges compassion. Nothing wrong with that as such. Heavens knows, it is not an either-or choice – the world needs both expanded empathy and compassion.

Another point of debate. When Brown says that taking a walk in the other person’s shoes is a myth that must be given up, she is rather overthinking what is a folk saying. Key term: overthinking (occupational hazard of all thinkers and academics).

“Talking a walk in the other person’s shoes” is the folk definition of empathy. Consider the situation from the perspective of the other person, especially if that individual is your critic, opponent, or sworn enemy. Especially if the latter is the case.

This is folk wisdom and appreciating the point requires a folkish charity. Key term: charity. It is uncharitable to take a saying and read it in a way that willfully distorts or makes it sound implausible or stupid. Ordinary common sense is required. This is what Brown properly calls a “near enemy” – for example, the way “pity” is the “near enemy” of empathy – a way of dismissing it.

Therefore, when one says take a walk in the other’s shoes, this is not a conversation about shopping therapy or shopping for shoes. It is a conversation about taking the other person’s perspective with the other’s life circumstances in view in so far as one can grasp those circumstances. If one wants to unpack the metaphor, the idea is to get an idea where the other person’s shoe pinches or chafes. One might argue that the metaphor breaks down if one uses one’s own shoe size. It does. It breaks down into projection, which would be a misfiring or breakdown of empathy. In being empathic, I do not want to know where the shoe pinches me, but rather where it pinches the other individual.

And that is a useful misunderstanding – as noted, what Brown elsewhere calls a “near enemy.” Empathic interpretation breaks down, fails, goes astray as projection. If I do not take into account differences in character and circumstances, then one is at risk of attributing one’s own issue or problem or emotion to the other person. It may be that we have to dispense with the word itself. “Empathy” has become freighted with too much semantics and misunderstanding. That is okay – as long as we double down and preserve the distinction empathy as a way of being in community and authentic relatedness, what Brown elsewhere calls meaningful connectivity. Still, the word “empathy” has its uses, and if the reader substitutes “empathy” for “meaningful connection” the sense is well preserved in both directions. Okay, keep the word.

If you have seen Brené Brown’s Netflix presentation (The Call to Courage”), then you know this woman is funny. Not standup comedy funny, she is after all an academic who broke out of the ivory tower into organizational transformation and motivational speaking. She knows how to tell a good story, often in a funny self-depreciating way, that makes one laugh at one’s own idiosyncrasies. Like packing three books for a vacation with the kids at Disney World. Who is one kidding, once again, except perhaps oneself? This approiach does not translate as well into print as one might wish. No one is criticizing Brown for not being Dave Barry, but, unless you are familiar with her “in person” routine, much of the humor is lost in translation. The author is sooo compassionate, that by halfway through the work, I was actually starting to experience compassion fatigue.

However, notwithstanding Brown’s aspiration to rigorous science, and she does have a claim to “big data.” For me, this is not the most valuable part of her contribution. I have been known to say, “We don’t need more data, we need expanded empathy.” The good news is that Brown displays both in abundance. As noted, one could substitute the word “empathy” for her uses of “connection” and “meaningful connection,” the topics of her dissertation and research program, and not lose any of the impact, meaning, or value. Empathy is no rumor in Brené Brown. Empathy lives in Brené Brown’s contribution.

References

Lou Agosta. (2010). “Heidegger’s 1924 Clearing of the Affects Using Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Book II.” Philosophy Today, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Winter 2010): 333–345. [Download paper: https://philpapers.org/rec/AGOHC-2 ]

© Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Compassion fatigue: A radical proposal for overcoming it

One of the criticisms of empathy is that is leaves you vulnerable to compassion fatigue. The helping professions are notoriously exposed to burn out and empathic distress. Well-intentioned helpers end up as emotional basket cases. There is truth to it, but there is also an effective antidote: expanded empathy.

For example, evidence-based research shows that empathy peaks in the third year of medical school and, thereafter, goes into steady decline (Hojat, Vergate et al. 2009; Del Canale, Maio, Hojat et al. 2012). While correlation is not causation, the suspicion is that dedicated, committed, hard-working people, who are called to a

Compassion Fatigue: Less compassion, expanded empathy?

life of contribution, experience empathic distress. Absent specific interventions such as empathy training to promote emotional regulation, self-soothing, and distress tolerance, the well-intentioned professional ends up as an emotionally burned out, cynical hulk. Not pretty.

Therefore, we offer a radical proposal. If you are experiencing compassion fatigue, stop being so compassionate! I hasten to add that does not mean become hard-hearted, mean, apathetic, indifferent. That does not mean become aggressive or a bully. That means take a step back, dial it down, give it a break.

The good news is that empathy serves as an antidote to burnout or “compassion fatigue.” Note the language here. Unregulated empathy results in “compassion fatigue.” However, empathy lessons repeatedly distinguish empathy from compassion.

Could it be that when one tries to be empathic and experiences compassion fatigue, then one is actually being compassionate instead of empathic? Consider the possibility. The language is a clue. Strictly speaking, one’s empathy is in breakdown. Instead of being empathic, you are being compassionate, and, in this case, the result is compassion fatigue without the quotation marks. It is no accident that the word “compassion” occurs in “compassion fatigue,” which is a nuance rarely noted by the advocates of “rational compassion.”

Once again, no one is saying, be hard hearted or mean. No one is saying, do not be compassionate. The world needs both more compassion and expanded empathy. Compassion has its time and place—as does empathy. We may usefully work to expand both; but we are saying do not confuse the two.

Empathy is a method of data gathering about the experiences of the other person; compassion tells one what to do about it, based on one’s ethics and values.

Most providers of empathy find that with a modest amount of training, they can adjust their empathic receptivity up or down to maintain their own emotional equilibrium. In the face of a series of sequential samples of suffering, the empathic person is able to maintain his emotional equilibrium thanks to a properly adjusted empathic receptivity. No one is saying that the other’s suffering or pain should be minimized in any way or invalidated. One is saying that, with practice, regulating empathy becomes a best practice.

Interested in more best practices in empathy? Order your copy of Empathy Lessons, the book. Click here.

References / Bibliography

M. Hojat, M. J. Vergate, K. Maxwell, G. Brainard, S. K. Herrine, G.A. Isenberg. (2009). The devil is in the third year: A Longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school, Academic Medicine, Vol. 84 (9): 1182–1191.

Mohammadreza Hojat, Daniel Z. Louis, Fred W. Markham, Richard Wender, Carol Rabinowitz, and Joseph S. Gonnella. (2011). Physicians empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients, Acad Med. MAR; 86(3): 359–64. DOI: 10.1097ACM.0b013e3182086fe1.

Louis Del Canale, V. Maio, X Wang, G Rossi, M. Hojat, and J.S. Gonnella. (2012). The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy, Academic Medicine, 2012; 87(9):1243–1249.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project