Home » Posts tagged 'empathic understanding'

Tag Archives: empathic understanding

Unreliable Parental Empathy in Henry James’ “What Maisie Knew”

Henry James provides a dramatic picture of unreliable and defective parental empathy. What Maisie Knew(1897) begins as a contentious divorce between Beale and Ida Farange is granted by the court. And, lacking the wisdom of Solomon (admittedly a rare quality), so is the custody of the child. The narrative is an inquiry into how the child is cut in half emotionally, and the consequences who she becomes as a person. Maisie is about six years old, and is to spend six months with each parent. As the story begins, each parent wants to take Solomon’s sword and use it on the other partner. Lacking a sword, they use Maisie. Or, expressed slightly differently, the parents are playing “hard ball” and Maisie is the ball.

James’ incomparable empathy with Maisie and his penetrating and astute comprehension of human relations writ large applies empathy in the extended sense as who people are as possibilities, walking in the other’s shoes (after, of course, first taking off one’s own to avoid projection), translating communications between adults and children (and adults and adults) as well as affect-matching and mis-matching (empathy in the narrow sense). James’ work aligns with the concise classic statement “On adult empathy with children” by Christine Olden (1953). When encountering a child, according to Olden, the adult is present to her or his own fate as a child of similar age. The encounter brings up the adult’s issues even if the child does not have such an issue and has other, unrelated issues. The adults expand their empathy by getting in touch with these issues and taking care that they not get in the way of their openness and responsiveness to the child. That, of course, is far from the case with the adults presented in James’ narrative. For example, in encountering Maisie, Mrs Wix (one of the governesses) is present not only to her own fate as a child, but to the fate of her (Mrs Wix’s) child, who was killed in a tragic traffic accident when she was about Maisie’s age. Mrs Wix reaction to her loses, including her own genteel poverty, is to embrace a scrupulous conventional morality that mainly constrains her (Mrs Wix), but which will also eventually impact Maisie. The parents, Beale and Ida, are nursing their grievances and elaborating their hostility to one another, as noted above, using Maisie. The prospective step-parents, Sir Claude and Miss Overmore (Mrs Beale), who eventually emerge, are a definite improvement in empathic responsiveness to Maisie. However, the bar is now set so low that is not saying a lot and the process of de-parenting and re-parenting does not succeed as the narrative ends due to Sir Claude’s unresolved marital status and Maisie’s own painfully acquired knowledge of how to play “hard ball” with the grown-ups.

As James’ novel begins, Maisie’s parents have already spent whatever financial resources they had as the divorce court enjoins Beale (the father) to return the 2500 pounds sterling to his former wife, which money, as noted, seems already to have been spent; Ida (the mother) is living off her looks, by the middle of the story, consorting with exceedingly unattractive rich men (Mr Perrin); Mr Faranago is doing the same with an American “Countess” of Color, who is described as having a mustache and it otherwise painted in terms of an appalling racist stereotype (definitely not James’ best moment). They are doing this for money. As Jems’ novels end, the one person of integrity – and it is narrowly scrupulous morality at that (people who are married should not move in with people to whom they are not married, even if the marriage is emotionally over (though not legally over)) – is Mrs Wix, whose inheritance (we learn towards the end) was stolen by a relative and, as the story of Maisie ends, has some slight hope of getting it back with the guidance of Sir Claude, who has heretofore not been particularly effective at anything except wooing an attractive, supposedly rich lady (Masie’s mother) who turned out not to be so rich and not so attractive if her personality is taken into the account. That noted, let us take a step back.

Children of tender age will repeat what is told them by way of a performance as if reciting a nursery rhyme, not appreciating the ramifications of the statements in the adult world. The reader is given a sample of misbehavior on the part of both parents. At this point, Maisie is six years old (p. 9). Her mother asks her:

‘And did your beastly, papa, my precious angel, send any message to your own loving mamma?’ Then it was that she found the words spoken by her beastly papa to be after all, in her little bewildered ears, from which, at her mother’s appeal, they passed, in her clear, shrill voice, straight to her little innocent lips, ‘He said I was to tell you, from him, she faithfully reported, ‘that your’re a nasty, horrid pig!’ (p. 11)

The way the parents use and, strictly speaking, misuse Maisie to send one another insulting, arguably abusive, messages marks both as loathsome individuals. These parents are easy to hate. The parents are verbally abusive towards one another, and abusive towards Masie in enrolling her in delivering invalidating messages on their behalf to one another. The text is packed with instances of inadequate, substandard parenting. The text is thick with examples of defective empathy, unreliable empathy, and even fiendish empathy. Breakdowns of empathy such as emotional contagion, projection, conformity, and communications lost in translation, are so pervasive as to make the text a veritable compendium of what parents ought not to do.

Maisie is reduced to a tool, and indeed even in Henry James’ skillful literary hands is something of a guinea pig in the jungle of parental incompetence and ethical conformity. The saving grace of James’ fictional study is that such scenarios, bordering on and perpetrating emotional abuse, are all too common – in his time and ours. The advantages of a fictional account is that it enables imaginative variations and thought experiments; and one is not going to get sued for slander, which is a risk even if the alleged “slander” is accurate and based on factual evidence.

The examples of Maisie’s parents are why 21st Century divorce judges begin proceedings by issuing a binding court order that the parents are not to speak ill of one another in front of the child nor have the child deliver messages to one another. I do not know the judicial practices in 1897. What I do know is that in 1897 divorce was less common and more scandalous in contrast with today when divorce is common and the scandals are single parent families, fatherless children, and domestic violence against women and children. We also know that the patriarchy was much more severe in times past (nor does that excuse today’s problems). Consider the cases of Anna Karenina (Leo Tolstoy, 1878) and Effi Briest (Theodor Fontane, 1895), who were prevented from seeing their children by spouses who were aggrieved, wielding ethical cudgels to separate mother and child. Yet even in our own time such legal injunctions are hard to enforce in cases where the parent is bound and determined to create mischief. Anecdotal reports from the trenches indicate that divorce judges are swamped with cases of physical abuse and inevitably give lower priority to bad verbal behavior, which can still be quite destructive to young, still maturing personalities.

Taking care of this child of tender age requires time and effort (all of which cost money) and each parent is eager to send Maisie to the other to inflict this cost on the despised former spouse. The child becomes an extension of the parent, like the narcissistic extension his or her own hand, the very definition of defective empathy, which leaves the child vulnerable to emotional disequilibrium, a kind of empty depression, and breakdowns in the child’s own empathy. The violation of the moral imperative to treat other people as ends in themselves and not mere means aligns with the parents’ retributive attitude, manipulative behavior, and (it must be said) pathological narcissism. Maisie becomes a mere means of the parents to inflict abuse on one other. While lonely and neglected, Maisie makes use of “auxiliary parents” such as an interested and engaged governesses and step parents (all of whom have their own conflicts of interest to maintain a measure of hope and perky positivity in the face of recurring disappointments delivered by the supposed adults in her world. Now in the context of the narrative, the governess, Miss Overbeck, is romantically interested in (and eventually marries) Maisie’s father; but Miss Overbeck also takes a sincere interest in Maisie. If Miss Overbeck is faking her interest in Maisie, it is an academy award winning performance. As in most areas of life, conflicting and overlapping interests are what make James’ narratives so powerful and thought provoking.

The matter almost immediately goes beyond James’ penetrating and engaging narrative. And that is relevance of James for us today. In our own time of fragmented and blended families, who does not know of an example where former spouses are at risk of speaking ill about one another? (It happens to married couples too!) The question is what happens when the affection or hostility are not expressed but nevertheless powerfully present, so to speak, percolating up from beneath the surface. That the emotions are not expressed means that they remain “unthought” as far as thinking using words is concerned. When Maisie’s father tells her, “Your mother hates you,” what does Maisie know about her mother and/or her father? The former spouses routinely refer abusively to their ex-partner in the presence of the child (as James calls her) in devaluing terms (p. 141) – “pig,” “nasty” person, “ass,” and so on.

When another person tells one something, then one has to decide whether to believe it or not. A whole course in critical thinking may be unfolded and inserted here. In particular, the child is motivated to believe the parents, because most decent parents tell the child the truth in age appropriate language, establishing a track record. Still, life events such as divorce, the birth of a sibling, major illness, or death of a family member, introduce incentives and emotional conflicts that distort communications and create parental integrity outages. Even in such examples, and this is the really interesting case, the child is incented to “go along with the program” – that is, what is represented as the truth about the life and family circumstances – because the parent provides meals, clothing, transportation, education, and entertainment, all of which are essential to the child’s well-being and immediate happiness. Still, while the child is constrained to “go along with the program” that does not mean the child always believes the outlandish assertions of the dominating parental authorities. Just because the child goes along with the parent’s fibs does not mean that the child always believes what she is told. You can’t fool all the people all of the time.

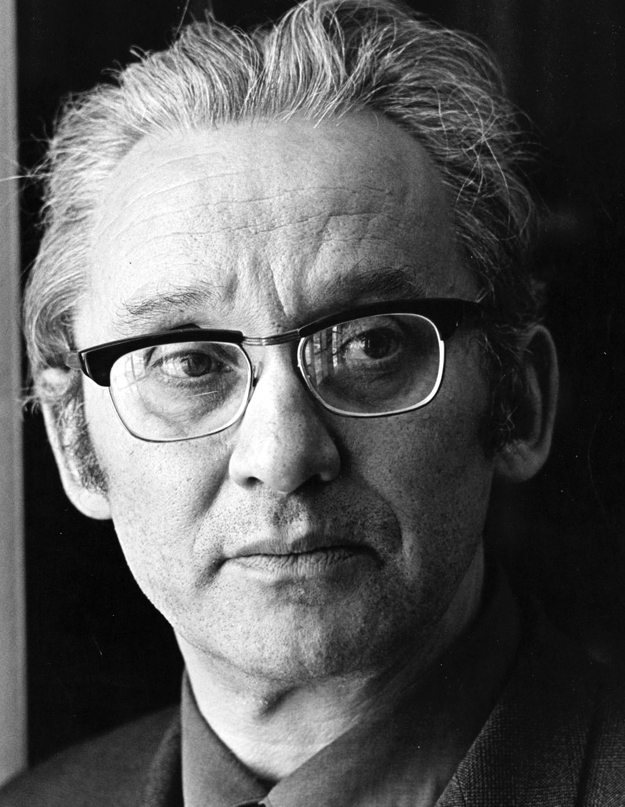

For example, at about the same time as James was writing his work, there was a precocious five-year-old – articulate, funny, witty, cute – living in Vienna to whom was born a baby sister. When he asked his parents from where the sister came (he was not quite sure a sister was such a good idea), the parents told him the stork brought it. At that point the boy’s behavior deteriorated, hough the connection and timing was overlooked by the parents, because of their own blind spots. The well-behaved boy threw temper tantrums, developed a phobia which made it difficult to take him out of the house, and regressed to baby-like behavior and talk. His father had a conversation with someone who was innovating in human development (Freud 1909). The coaching was – stop lying to the kid and tell him about from where babies come – tell him about the birds and bees. Recovery was prompt – though there were other challenges in the relationship between his parents.

The point? Children often know that they do not have all the facts and being dependent on their parents for their well-being the children decide it is best to conform. (Key term: conform.) They accept what they are told, subject to their own observations. The boy in question, anonymously known as “Little Hans,” had access to the lake where the storks were living and he saw the storks, but there was a noticeable absence of human babies (Freud 1909). Young scientist! Astutely observant, Hans concluded that his parents account was a fabrication. In short, they were lying to him about from where babies came. Unable to express himself in adult (scientific) language with the counter-example produced by his own observations down by the lake, Hans acted out. His behavior deteriorated. His behavior expressed his disagreement and his suffering, In short, he “knew” his folks were lying to him, rather in the sense that Maisie “knew” matters were not well with the representations offered by the adults in her environment.

Thus, the one parent says, “Your father is loathsome.” The other parent says, “Your mother is loathsome.” Unlike the story about the stork, both of Maisie’s parents are speaking the truth! Yet even in uttering what is a factually accurate statement, there is a larger integrity outage confounding circumstances for the child. It is the job of the parents to take care of the whole child, and they seem not even to have the idea what is the “whole child” and how to do their job. Yes, of course, the child’s material needs, but also the child’s emotional development, education, and sense of being an effective agent, even if only in age appropriate, childish matters. That is profoundly missing here. In such a context, the factually accurate words are a lie.

In the case of Maisie, what might be called intrusive interruptions – and the pediatrician psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott calls “impingements” – in her childhood tasks of precisely being allowed to be a child of tender age, learning her school lessons, playing with children of a similar age, and holding tea parties with her dolls and stuffed animals – occur as the grown ups treat Maisie like a grown up. Her nursery attendant tells her: “Your papa wishes you never to forget, you know, that he has been dreadfully put about” (p. 10). This is the paradigm of defective empathy, for it attempts to induce in the child what papa was experiencing, yet does so in way that blames the child – points an accusing finger at her – for the “dreadful” inconvenience papa is suffering because of shared child custody. The child’s job is to learn her school lessons, play with her dolls, have bed time story time and lunch time and bath time, and visit with her peers (of which Maisie seems to have none), not to understand legal custody proceedings.

In general, when confronted with incompetent parenting, the child will (1) try to “fix the parent” so the parent can do her/his job (of taking care of the child), (2) conform, or (3)act out (see Little Hans, above). For example, the child will try to cheer up the depressed mother by putting on a happy smiley face, being perky, winsome, in the face of the mother’s self-invovled funk and indifference. The middle school or pubertal child will quote positive things said by friends about the parent. The child will try to placate the neglectful, abandoning, or angry father by being apologetic, giving agreement, being submissive, promising “I’ll be good!” The child may have no idea what is bothering the grown up – financial challenges, health issues, sexual frustration, or relationship breakdowns that a child of tender age cannot possibly comprehend. The child may act out – if an adolescent, defy social conventions – if a child of tender age, regress and lose toilet skills and wet the bed. The child will experience difficulties – experience sleep and eating disorders or throw temper tantrums. The child has limited skill in expressing her or his feelings verbally and/or understanding parental issues, so the child will invent meaning. “If only I were better at academics, sports, socializing, doing chores, then my mother and/or father would be happy (and be able to take care of me in such a way that I can be happy too).” “If only I had done my chores, my folks would not be getting divorced” – and this after both parents have repeatedly assured the child that she or had nothing to do with the family breakup.

In the narrative, mamma enacts a similar impingement and calls forth a “try to fix her” response in Maisie. Papa has already used the same words:

You’ll never know what I’ve been through about you – never, never, never. I spare you everything, as I always have [….] If you don’t do justice to my forbearing, out of delicacy, to mention, just as a last word, about your stepfather, a little fact or two of a kind that really I should only have to mention to shine myself in comparison and after every calumny like pure gold: if you don’t do me that justice you’ll never do me justice at all.

Maisie’s desire to show what justice she did her had by this time become so intense as to have brought with it an inspiration (p, 161)

In response, Maisie tries to cheer up her mother – tries to “fix” things by acknowledging her mother with the complimentary description of Ida (mamma) provided by The Captain, a prospective romantic interest of mamma with whom Maisie had a conversation. The Captain had paid her (mamma) many credible compliments, saying beautiful, kind things about her, which helped Maisie feel genuine affection for this difficult individual, Maisie’s mamma. Maisie tries to acknowledge her mamma using the Captain’s kind words. It does not work. “Her [Maisie’s] mother gave her one of the looks that slammed the door in her face; never in a career of unsuccessful experiments had Maisie had to take such a stare” (p. 164). James compares the impact on Maisie to a science experiment that goes horribly wrong, producing something disgusting instead of the expected elegant result. The mother then has a temper tantrum. Maisie (who is now estimated to be the age of a middle school student) survives this scene of “madness and desolation,” “ruin and darkness,” and, after mamma’s departure, goes off and smokes cigarettes with Sir Claude.

As noted, Winnicott describes this scene of fear and defective empathy, “…[T]he faulty adaptation to the child, resulting in impingement of the environment so that the individual [the child] must become a reactor to this impingement. The sense of self is lost in this situation and is only regained by a return to isolation” (Winnicott, 1952: 222; italics added). Maisie is definitely isolated, and she suffers greatly because of it. The parent takes the child as his or her confidant as if the child were an adult, “Let me tell you what your father said.” “Let me tell you what your mother did.” Even when the content of the statement is relatively benign, the tone with which it is uttered – and that is the moment of defective empathy – causes the listener to imagine a kind of outrage, boundary violation, or integrity outage. This other must be the very devil!

In the case of What Maisie Knew, both parents are explicitly hostile towards one another and, if not hostile towards Maisie (though that too emerges), at least neglectful and manipulative. Arguably, in making Masie the means of their abuse of one another, the parents are also abusing her. However, what about the case, perhaps more common in our own supposedly psychologically advanced time, where the parent is hostile, but following the court order, the parent does not express it. What happens then? That of course goes beyond James’ narrative, but points to its relevance for our own challenges and struggles.

On a positive note, if the abusive language is not performed, then it is not in the space. In so far as children are designed to conform to the guidance of their parents – even when they do not fully believe or trust them – so much negativity is removed from the space. Well and good – at least there is nothing to present in court when going before the judge. You will never hear me say that it is better to use the abusive language for then one knows where one stands with the other person. There are many other, better, ways of figuring out where one stands with the other such as comparing words and deeds, confronting one’s own introspective empathy, or simply asking the other person or other significant actors in the environment. It is just that the child’s ability to do these things is still developing and may be inadequate to the task (a problem that less skilled adults (and there are many) may also face). The hostility does not appear on the surface, which gives the appearance of a calm and placid body of water; yet a rip tide may lurk beneath the surface, capable of pulling one down.

At this point, it is useful to take a step back and consider how our consciousness is populated with many voices and many actors. An example of an “internal object” (actually more of an agent) would be a conscience that “tells” the person about the rightness of a prospective or accomplished behavior or speech act. The first internal object, the conscience (“superego”) is formed, thanks to the mechanism of identification with the aggression (about which more shortly). The conscience can become a hostile introject along other internal objects such as images of the parents, mentors, and positive complexes such as generosity, compassion, and empathy. The proposal is that the difference between parents who are explicitly assaultive in their speech acts and those who bottle up the hostility, which then leaks out in indirect forms, shows up in the quality of the internal introject. In the first case, the introject is more hostile, harsher but easier to distinguish from the authentic self; in the second case, the introject is more benign, but not necessarily harmless, and yet harder to distinguish from the authentic self.

If one could truly cancel all the hostility – not just try to keep it down – but truly extirpate it, then it would become an idle wheel and not move any part of the behavior or thinking of the agents in question. But would the hostility then exist anymore? It would be unexpressed, because it really and truly were sublimated into a poem or work of art. That is the issue – is there ever such a thing as unexpressed hostility? This is not a problem that Maisie’s parents have – their problem is that they are embracing the hostility, elaborating it, making it their project. The damage (including to the parents) is substantial. In contract, when the hostility is unexpressed, but still lurking beneath the surface, it may not be unexpressed forever. Betrayal oozes at every pore. empathy is active here too, in a kind of regressive mode, and gives off hostile vibes, aggressive vibes, even if one’s words as sweet as honey. “Would you like another piece of cake?” Is spoken with such a tone of venom that one suspects the cake might contain arsenic. The tone is the moment of empathy (or, more precisely, the unempathic moment) in which one gives off a kind of negative affect, a hostile vibe, in spite of one’s sweet or benigh words. In addition, it is just as common for hostility which is not verbally expressed to be displaced or expressed indirectly in behavior and deed. With advance apologies to pet lovers, the boss bullies the employee and the employee goes home and kicks the dog. The hostility is present but displaced.

As Maisie’s papa gets ready to leave for American to attend to the business affairs of his new, rich consort, the princess, further unreliable empathy. He makes an invitation to Maisie to accompany him to America. This is “out of the blue,” without context or assurances as to how Maisie will be taken care of, and the offer is fake. Why fake? Because he really does not want her along, nor does she really want to go, even though she says with enthusiasm and e=repeatedly “I will follow you anywhere.” It is clear the adventure is not going to happen:

She [Maisie] began to be nervous again; it rolled over her that this was their parting, their parting forever, and that he [papa] had brough her there for so many caresses only because it was important such an occasion should look better for him than any other [….]It was exactly as if he had broken out to her: ‘I say, you little donkey, help me to be irreproachable, to be noble, and yet to have none of the beastly bore of it. There’s only impropriety enough for one of us; so you must take it all (p 138).

Naturally, the child has to go along with what the parent tells her or him. The parent has the power to provide meals, transportation, shelter and entertainment, though, in this case, none are offered.

The cost and the impact of the lack of integrity and empathy (and adaptation in general) of the parents to the child is the creation of a false self. Maisie pretends to be dumb. The trouble is that faking being dumb risks actually being dumb in a “fake it till you make it” moment. Her formal education is already neglected and in tatters. Now in the context of James’ narrative, Maisie never loses her cognitive acumen, though she gets called invalidating names such as “idiot” and “donkey” by her elders, which must have a damaging impact on her self-esteem.

Here James is the master psychologist ahead of his time, giving the reader an inside case history on the production of what, as noted, D. W. Winnicott came to describe as “the false self.” On background, Winnicott is the pediatrician who became a celebrated psychoanalyst, surviving an analysis with James Strachey, Melanie Klein, who was himself fortified intellectually by one his most famous (indeed infamous) students and colleagues, Masud Kahn. Without going into psychoanalytic politics, let’s just say that Winnicott’s ideas of the transitional object, virtual play space of creativity, and the false self are among the most enduring and time-tested contributions of child analysis.

At risk of over-simplification, the false self is constructed in order to protect the true self, the source of spontaneity, satisfaction, fulfillment, beginning something new (as Hannah Arendt would say), and creativity. The false self is designed to help the individual survive the impingements of caretakers whose empathy is faulty. Here “empathy” is understood in the extensive sense of the parent’s willingness and ability to adapt to the requirements of the maturing child. The child is an end in her- or himself and not an extension of the parent’s narcissism, which narcissism reduces the child to the role of fulfilling the parents’ unmet needs in their own lives. Unhappy the child who must compensate for what is missing in the parents’ own lives. Most children will try to do so, making reparation for another’s incompletenesses, conforming to the felt requirements of the parent. How do you think that is going to work for the child?

Maisie’s authentic self takes shelter, hides, behind the false one and preserves the hope of someday being able to be expressed and have a satisfying life of her own, but in the meantime Maisie is able to get the secondary gain of frustrating her parents is using her to hurt one another. Maisie acquires the “know how” required to survive by manipulating the manipulators. The cost is enormous, but it protects one from the impingements of the powerful, malevolent forces in the unempathic environment:

The theory of her stupidity, eventually embraced by her parents, corresponded with a great date in her small, still life [….] She [Maisie] had a new feeling, the feeling of danger; on which a new remedy rose to meet it, the idea of an inner self, or, in other word, of concealment. She puzzled out with imperfect signs, but with a prodigious spirit, that she had been a centre of hatred and a messenger of insult, and that everything was because she had been employed to make it so. Her parted lips locked themselves with the determination to be employed no longer. She would forget everything, she would repeat nothing, and when, as a tribute to the successful application of her system, she began to be called a little idiot, she tasted a pleasure altogether new. When therefore, as she grew older, her parents in turn, in her presence, announced that she had grown shockingly dull, it was not from any real contraction of her little stream of life. She spoiled their fun, but she practically added to her own (p. 13; see also p. 54 on “the effect of harmless vacancy”; see also p. 117 on deep “imbecility”).

The child lives into – and unwittingly lives up to – the devaluing description and expectations made of her. Maisie makes the best of a bad situation and has fun spoiling the fun of other (which “fun” seems to be the mutual insults of and gossip about the parents). But the cost is substantial. James’ calls out a masochistic moment here in which, as the proverb goes, one cuts off one’s nose to spite one’s face. Caught in the cross fire, in an attempt to find a way between the rock and the hard place, Maisie consults a potential ally. Miss Overmore (the governess initially employed by her mother, but who eventually marries her father) has conflicts of interest of her own but in this moment functions as an honest broker. Maisie’s mother tells her to tell her father that he is a liar and Maisie, who is maturing, asks her governess if she should do so:

‘Am I to tell him?’ the child [Maisie] went on. It was then that her companion [Miss Overmore] addressed her in the unmistakable language of a pair of eyes deep dark-grey. ‘I can’t say No,’ they replied as distinctly as possible; ‘I can’t say No, because I’m afraid of your mamma, don’t you see? Yet how can I say Yes after your papa has been so kind to me, talking to me so long the other day, smiling and flashing his beautiful teeth at me the tie we met him in the Park, the time when, rejoicing at the sight of us [….]The wonder now lived again, lived in the recollection of what papa had said to Miss Overmore: ‘I’ve only to look at you see that your’re a person to whom I can appeal to help me save my daughter.’ Maisie’s ignorance of what she was to be saved from didn’t diminish the pleasure of the thought that Miss Overmore was saving her. It seemed to make them cling together (p. 15).

What Maisie does is she keeps quiet. She isolates – plays dumb. All the worse, the mother initially prevents Miss Overmore from accompanying Maisie when the rotation to the father’s turn to take care of her occurs. The child is afraid of being abandoned – not taken care of – not provided for. Miss Overmore is taking caring of Maisie educationally and emotionally. Miss Overmore is banished (at least at this point). The child is “invisible”: “Maisie had a greater sense than ever in her life before of not being personally noticed (p. 107).

As the novel progresses, mamma is stricken with a dreaded but unspecified disease and her life is limited by illness even as she consorts with men who have money. As noted, Papa is bound for America. Sir Claude (who has not been properly introduced here but is a kind person who marries Maisie’s mother and genuinely likes Maisie) ping pongs between England and Paris as Sir Clause learns of a letter in which Papa (Mr Beale) deserts Mrs Beale (Miss Overmore, now Sir Claude’s lover). “You do what you want – and so will I” type of arrangement. Sir Claude is still married to mama (Ida Farange), and in the gilded age that is the scandal. Sir Claude cannot live with a woman married to someone else (according to the standard conventions of the time). There is something indecent about Sir Claude taking up with Miss Overmore while still technically married to Ida. Key term: indecent.

The novel itself has an unthought, regarding the conventions circa 1897 about adult sex outside of marriage and within marriage with other partners. Sir Claude’s is a person who does not speak unkindly of anyone. He is kind, albeit a chain smoker, which is perhaps a way of binding his underlying anxiety. He is happy to have been given permission to do what he wants by his wife (Ida, Masie’s mother) provided she gets similar permission to consort with whoever she wishes. Without a formal divorce, this leaves Sir Claude compromised in terms of conventional moral standards (which were much stronger in such matters in 1897 than in 2024).

We fast forward though Maisie’s lessons in cynicism, playing “hard ball,” the integrity outages of her parents and step parents, and instruction from another of her governesses, Miss Wix, in a rigorous sense of conventional morals. As the story ends (spoiler alert!), Maisie practices a kind of hardball. “I will give up Mrs Wix if you will give up Miss Overmore – and we will go off together to Paris,” Maisie proposes to Sir Claude. Both governesses are to be thrown “under the bus,” which does have a certain narrative symmetry and symbolizes Maisie’s gorwing up.

Thus, Maisie tries to seduce Sir Claude, who, as noted, is the handsome if ineffective 2nd husband of her mamma. “Everyone loves Sir Claude,” everyone except his wife (Maisie’s mama). After marrying mamma, Sir Claude falls in love with Miss Overmore (who has since married Papa). Maisie proposes that she will give up Miss Wix if Sir Claude gives up Miss Overmore. That is the “seduction.” There is a certain amount of back-and-forth negotiation, but it is clear this is never seriously considered by Sir Claude. He would be willing to be in Maisie’s life, but is committed to living near Miss Overmore (Mrs Beale) in France (who are notoriously loose regarding marriage boundaries) so Sir Claude and Miss Overmore can continue their romance. Maisie (as directed by the author, James) takes the moral high road, and returns to England with her strict governess Miss Wix to a life of genteel poverty and “moral sense,” which means conformity to conventional moral behavior.

The empathic moment for Maisie is, who is she as a possibility? This is an aspect of empathy that is sometimes overlooked in the conversations about affect matching, projection, and communications lost in translations – who is the person as a possibility. For example, I meet someone is who struggling with alcohol abuse or, in this case, with quasi-abusive, neglectful parents. That is not who the person is authentically as a possibility. The abuser of alcohol is the possibility of overcoming that she is drinking because of unresolved trauma, low self-esteem, or other specific issue, which when surfaced and worked through allow the person to write the great American novel, join Doctors without Borders, or start a family.

So, once again, who is Maisie as a possibility? First of all, she is a survivor of being “caught in the cross fire” of a nasty divorce and being raised in its shadow. Anyone proposing to give Maisie a good listening might find themselves responding to her empathically saying, “You may usefully know yourself as a survivor.” By the end of the narrative, as Maisie goes off with her governess, Miss Wix, it far from clear that is the case. So while Maise learns a lot about cynicism, hardball, interpersonal invalidation, perpetrations, and emotional intrigue, she does not yet know herself as a survivor.

Using James’ other female figures as a foil for who is Maisie as a possibility, maybe she becomes a kind of Kate Croy (as in James’ Wings of a Dove) scheming to get married to get someone else’s fortune upon their passing away. Maybe Maisie becomes Maggie (as in The Golden Bowl), sacrificing herself to the happiness of others and simultaneously validating the appearances of conventional morality. Or perhaps she becomes a Miss Overmore, a governess educating other people’s children in French grammar and romantic intrigues with the master of the house. Alternatively, Maisie becomes a governess such as Mrs Wix, not mourning the loss of a daughter, but the loss of her own possibility of satisfaction by means of a scrupulous morality, a reaction formation to the loose standards of her own parents and step parents. As the narrative concludes, the latter is the probable almost certain future. A sad ending indeed.

There are many moments of affect matching (and mismatching) in James. There are many moments of communications lost in translation. These are empathy lessons in the sense that if one “cleans up” the miscommunication (restore understanding, then empathy emerges between the communicants. There are many examples of projection in – the parents especially are projecting their hostility onto one another and indeed everyone in the environment. Withdraw the project and authentically be with the other person and empathy comes forth. This does not happen to the parents, but the step parents (with whom Maisie is prospectively “re-parented”) move in that direction. Does Maisie become Kate Croy, Maggie (albeit without all the money), or even a version of her own mamma, seeking her fortune (literally) in association with a series of men of varying degrees of unattractiveness The opportunities for women are appallingly limited. Maisie’s education has been neglected as she has been shunted back and forth between parents. Even when she is de-parented from her biological ones, and Sir Claude and Miss Overmore (Mrs Beale) come together and propose to take care of her, the promise of educational lectures is short-circuited by lack of a revenue model. They can afford some lectures targeting working class folks at the equivalent of the public library, but university level preparation (which, at that time, requires Greek and Latin) seems a high bar. The disappointing, even demoralizing (in the sense of inspiring a righteous indignation), results are a reduction to absurdity of the constraints of standard morality. There is no need for James explicitly to have intended such a message, but it is not hard to find it in him, consistent with an agenda that treats women as full human beings, social actors, and agents with full political and financial rights (which was definitely not the case in James’ Gilded Age).

James’ novels often end on a conventional note, even if his embrace of convention is a reduction to absurdity of convention. When Maisie sees her parents nasty divorce, relatively rare in 1896 as compared with our own time, and the musical chairs of changing partners with Sir Claude and Miss Overbeck (Mrs Beale), is it any wonder that Maisie embraces conventional morality and partners with Mrs Wix, a standard governess who has lost a daughter that would be about Maisie’s age? As noted above, when Mrs Wix is in the presence of Maisie, she (Mres Wix) is in the presence of her lost daughter, which presents an obstacle to her being with – that is, empathizing with – Maisie. Instead Mrs Wix goes to morality (not inconsistent with empathy, just different than it) and her advocacy with “moral sense.” At this point, James’ incomparable empathy gives way to crafting a writerly conclusion, which engages and reduces conventional morality to absurdity.

Much ink has been spilt on whether James’ endings are endorsed by him. Happy endings are rare in the real world, and if one considers death to be unhappy, then they never occur. Never. However, endings where the protagonists act conventionally are realistic in the sense that people often conform to conventional moral standards – which is why it is called “convention.”

A deeper level of integrity coincides with doing what is conventional in James’ Wings of a Dove. Maggie returns to her unfaithful husband, Prince Amerigo, doing what is superficially conventionally requires. The arguably “deeper” integrity of Maggie’s self-sacrifice for the happiness of the poor couple (the husband and his original love interest) is hard to understand under the draconian laws of the patriarchy, by which the unfaithful husband has control of Maggie’s financial fortune. Maggie decides to “fund” his unfaithfulness to her in a magnanimous gesture of self-sacrifice (but does she really have a choice?) based on the romantic notion that his love for his prospective bride from their days of mutual impoverishment was the “real thing.” There is no way that life has to look, and it will turn out the way that it turns out.

In a different context and narrative, Lambert Strether (The Ambassadors) honors his word in the most superficial sense, returning to America presumably to acknowledge that, though Chad returns to Woollett, he (Strether) tried to convince him not to do so, requiring the engagement of other ambassadors, and forgoing his (Strether’s) own possibility of happiness with Marie, which would have required him explicitly to break his word and not return. Thus, doing the conventionally “right thing” is the wrong thing from the perspective of a personally satisfying outcome.

In the background is the pervasive issue of what is the revenue model? Who has the money? Kate Croy and Merton Denscher are engaging in a confidence scheme to get Milly Theale’s fortune (she has a fatal disease). Denscher is belatedly overcome with integrity (and Kate’s refusal to have sex with him to confirm the shady deal), not conventional conformity, but actual remorse. It cancels his affection for Kate, who poverty previously prevented him from marrying. Unless one thinks Milly’s bequest is a “guilt trip” designed to punish Denscher (which it might be, but probably not), and not a genuine gift to someone Milly loved, a case can be made that the non-conforming thing to do would be to “take the money and run (to the bank).” Here the layers of ambiguity and uncertainty really do send the participants (and readers) spinning (Pippin 2000: 66), and no reason exists to believe an unambiguous “right answer” is available. In the Golden Bowl, Maggie has the money, until she doesn’t, and that makes all the difference.

That Maisie turns out with standard level neuroses, acting out an Oedipus complex, even if cynical and seductive in a way conventionally appropriate for women of the Gilded Age, and not psychotic, is a tribute to the secure attachment she experienced from her early nurse, Moddle, all of which must have occurred prior to the beginning of the narrative.

Bibliography

S. Freud. Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 10:1-150

Henry James. (1897). What Maisie Knew. New York, Penguin Classics, 2007.

Christine Olden. (1952). On adult empathy with children. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 8: 111–126.

Robert Pippin. (2000). Henry James and Modern Moral Live. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Winnicott, D. W. (1952). Psychoses and child care. In D. W. Winnicott (1958).

Collected Papers. London: Tavistock Publications.

Juneteenth: Beloved in the Context of Radical Empathy

For those who may require background on this new federal holiday, June 19th – Juneteenth – it was the date in 1865 that US Major General Gordon Granger proclaimed freedom for enslaved people in Texas some two and a half years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Later, the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution definitively established this enshrining of freedom as the law of the land and, in addition, the 14th Amendment extended human rights to all people, especially formerly enslaved ones. This blog post is not so much a book review of Beloved as a further inquiry into the themes of survival, transformation, liberty, trauma – and empathy. (By is a slightly updated version of an article that was published on June 27, 2023.)

“Beloved” is the name of a person. Toni Morrison builds on the true story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved person, who escaped with her two children even while pregnant with a third, succeeding in reaching freedom across the Ohio River in 1854. However, shortly thereafter, slave catchers (“bounty hunters”) arrived with the local sheriff under the so-called fugitive slave act to return Margaret and her children to slavery. Rather than submit to re-enslavement, Margaret tried to kill the children, also planning then to kill herself. She succeeded in killing one, before being overpowered. The historical Margaret received support from the abolitionist movement, even becoming a cause celebre. The historical Margaret is named Sethe in the novel. The story grabs the reader by the throat – at first relatively gently but with steadily increasing compression – and then rips the reader’s guts out. The story is complex, powerful, and not for the faint of heart.

The risks to the reader’s emotional equilibrium of engaging with such a text should not be underestimated. G. H. Hartman is not intentionally describing the challenge encountered by the reader of Beloved in his widely-noted “Traumatic Knowledge and Literary Studies,” but he might have been:

“The more we try to animate books, the more they reveal their resemblance to the dead who are made to address us in epitaphs or whom we address in thought or dream. Every time we read we are in danger of waking the dead, whose return can be ghoulish as well as comforting. It is, in any case, always the reader who is alive and the book that is dead, and must be resurrected by the reader” (Hartman 1995: 548).

Waking the dead indeed! Though technically Morrison’s work has a gothic aspect – it is a ghost story – yet it is neither ghoulish nor sensational, and treats supernatural events rather the way Gabriel Garcia Marquez does – as a magical or miraculous realism. Credible deniability or redescription of the returned ghost as a slave who escaped from years-long sexual incarceration is maintained for a hundred pages (though ultimately just allowed to fade away). Morrison takes Margaret/Sethe’s narrative in a different direction than the historical facts, though the infanticide remains a central issue along with how to recover the self after searing trauma and supernatural events beyond trauma. The murdered infant had the single word “Beloved” chiseled on her tombstone, and even then the mother had to compensate the stone mason with non-consensual sex. An explanation will be both too much and too little; but the minimal empathic response is to try to say something that will advance the conversation in the direction of closure, the integration of unclaimed experience (to use Cathy Carruth’s incisive phrase), and recovery from trauma. Let us take a step back.

Morrison is a master of conversational implicature. What is that? “Conversational implicature” is an indirect speech act that suggests an idea or thought, even though the thought is not literally expressed. Conversational implicature lets the empathy in – and out – to be expressed. Such implicature expands the power and provocation of communication precisely by not saying something explicitly but hinting at what happened. The information is incomplete and the reader is challenged to feel her/his way forward using the available micro-expressions, clues, and hints. Instead of saying “she was raped and the house was haunted by a ghost,” one must gather the implications. One reads: “Not only did she have to live out her years in a house palsied by the baby’s fury at having its throat cut, but those ten minutes she spent pressed up against dawn-colored stone studded with star chips, her knees wide open as the grave, were longer than life, more alive, more pulsating than the baby blood that soaked her fingers like oil” (Morrison 1987: 5–6). Note the advice above about “not for the faint of heart.”

The reader does a double-take. What just happened? Then a causal conversation resumes in the story about getting a different house as the reader tries to integrate what just happened into a semi-coherent narrative. Yet why should a narrative of incomprehensibly inhumane events make more sense than the events themselves? No good reason – except that humans inevitably try to make sense of the incomprehensible.“Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief” (1987: 6). One of the effects is to get the reader to think about the network of implications in which are expressed the puzzles and provocations of what really matters at a fundamental level. (For more on conversational implicature see Levinson 1983: 9 –165.)

In a bold statement of the obvious, this reviewer agrees with the Nobel Committee, who awarded Morrison the Novel Prize in 1988 for this work. This review accepts the high literary qualities of the work and proposes to look at three things. These include: (1) how the traumatic violence, pain, suffering, inhumanity, drama, heroics, and compassion of the of the events depicted (consider this all one set), interact with trauma and are transformed into moral trauma; (2) how the text itself exemplifies empathy between the characters, bringing empathy forth and making it present for the reader’s apprehension; (3) the encounter of the reader with the trauma of the text transform and/or limit the practice of empathizing itself from standard empathy to radical empathy.

So far as I know, no one has brought Morrison’s work into connection with the action of the Jewish Zealots at Masada (73 CE). The latter, it may be recalled, committed what was in effect mass suicide rather than be sold into slavery after being militarily defeated and about-to-be-taken-prisoner by the Roman army. The 960 Zealots drew lots to kill one another and their wives and children, since suicide technically was against the Jewish religion.

On further background, after the fall of Jerusalem as the Emperor Titus put down the Jewish rebellion against Rome in 73 CE, a group of Jewish Zealots escaped to a nearly impregnable fortress at Masada on the top of a steep mountain. (Note Masada was a television miniseries starring Peter O’Toole (Sagal 1981).) Nevertheless, Roman engineers built a ramp and siege tower and eventually succeeding in breaching the walls. The next day the Roman soldiers entered the citadel and found the defenders and their wives and children all dead at their own hands. Josephus, the Jewish historian, reported that he received a detailed account of the siege from two Jewish women who survived by hiding in the vast drain/cistern – in effect, tunnels – that served as the fortress’ source of water.

The example of the Jewish resistance at Masada provides a template for those facing enslavement, but it does not solve the dilemma that killing one’s family and then committing suicide is a leap into the abyss at the bottom of which may lie oblivion or the molten center of the earth’s core, a version of Dante’s Inferno. So all the necessary disclaimers apply. This reviewer does not claim to second guess the tough, indeed impossible, decisions that those in extreme situations have to make. One is up against all the debates and the arguments about suicide.

Here is the casuistical consideration – when life is reduced from being a human being to being a slave who is treated as a beast of burden and whose orifices are routinely penetrated for the homo- and heteroerotic pleasure of the master, then one is faced with tough choices. No one is saying what the Zealots did was right – and two wrongs do not make a right – but it is also not obvious that what they did was wrong in the way killing an innocent person is wrong, who might otherwise have a life going about their business gardening, baking bread, or fishing. This is the rock and the hard place, the devil and deep blue sea, the frying pan or the fire, the Trolley Car dilemma (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem). This is Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox, who after the unsuccessful attempt in June 1944 to assassinate Hitler (of which Rommel apparently had knowledge but took no action), was allowed by the Nazi authorities to take the cyanide pill. This is Colonel George Armstrong Custer with one bullet left surrounded by angry Dakota warriors who would like to slow cook him over hot coals. Nor as far as I know is the bloody case of Margaret Garner ever in the vast body of criticism brought into connection with the suicides of Cicero and Seneca (and other Roman Stoics) in the face of mad perpetrations of the psychopathic Emperor Nero. This is a decision that no one should have to make; a decision that no one can make; and yet a decision that the individual in the dilemma has to make, for doing nothing is also a decision. In short, this is moral trauma.

A short Ted Talk on trauma theory is appropriate. Beloved is so dense with trauma that a sharp critical knife is needed to cut through it. In addition to standard trauma and complex trauma, Beloved points to a special kind of trauma, namely, moral trauma or as it sometimes also called moral injury, that has not been much recognized (though it is receiving increasing attention in the context of war veterans (e.g. Shay 2014)). “Moral trauma (injury)” is not in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), any edition, of the American Psychiatric Association, nor is it even clear that it belongs there, since the DSM is not a moral treatise. Without pretending to do justice to the vast details and research, “trauma” is variously conceived as an event that threatens the person’s life and limb, making the individual feel he or she is going to die or be gravely injured (which would include rape). The blue roadside signs here in the USA that guide the ambulance to the “Trauma Center” (emergency department that has staff on call at all times), suggest an urgent emergency, in this case usually but not always, a physical injury.

Cathy Caruth (1996) concisely defines trauma in terms of an experience that is registered but not experienced, a truth or reality that is not available to the survivor as a standard experience, “unclaimed experience.”The person (for example) was factually, objectively present when the head on collision occurred, but, even if the person has memories, and would acknowledge the event, paradoxically, the person does not experience it as something the person experienced. The survivor experiences dissociated, repetitive nightmares, flashbacks, and depersonalization. At the risk of oversimplification, Caruth’s work aligns with that of Bessel van der Kolk (2014). Van der Kolk emphasizes an account that redescribes in neuro-cognitive terms a traumatic event that gets registered in the body – burned into the neurons, so to speak, but remains sequestered – split off or quarantined – from the person’s everyday going on being and ordinary sense of self. For both Caruth and van der Kolk, the survivor is suffering from an unintegrated experience of self-annihilating magnitude for which the treatment – whether working through, witnessing, or (note well) artistic expression – consists in reintegrating that which was split off because it was simply too much to bear.

For Dominick LaCapra (1999), the historian, “trauma” means the Holocaust or Apartheid (add: enslavement to the list). LaCapra engages with how to express in writing such confronting events that the words of historical writing and literature become inadequate. The words breakdown, fail, seem fake no matter how authentic. And yet the necessity of engaging with the events, inadequately described as “traumatic,” is compelling and unavoidable. Thus, LaCapra (1999: 700) notes: “Something of the past always remains, if only as a haunting presence or revenant.” Without intending to do so, this describes Beloved, where the infant of the infanticide is literally reincarnated, reborn, in the person named “Beloved.” For LaCapra, working through such traumatic events is necessary for the survivors (and the entire community) in order to get their power back over their lives and open up the possibility of a future of flourishing. This “working through” is key for it excludes denial, repression, suppression, and, in contrast, advocates for positive inquiry into the possibility of transformation in the service of life. Yet the attempt at working through of the experiences, memories, nightmares, and consequences of such traumatic events often result in repetition, acting out, and “empathic unsettlement.” Key term: empathic unsettlement. From a place of safety and security, the survivor has to do precisely that which she or he is least inclined to do – engage with the trauma, talk about it, try to integrate and overcome it. Such unsettlement is also a challenge and an obstacle for the witness, therapist, or friend providing a gracious and generous listening.

LaCapra points to a challenging result. The empathic unsettlement points to the possibility that the vicarious experience of the trauma on the part of the witness leaves the witness unwilling to complete the working through, lest it “betray” the survivor, invalidate the survivor’s suffering or accomplishment in surviving. “Those traumatized by extreme events as well as those empathizing with them, may resist working through because of what might almost be termed a fidelity to trauma, a feeling that one must somehow keep faith with it” (DeCapra 2001: 22). This “unsettlement” is a way that empathy may breakdown, misfire, go off the rails. It points to the need for standard empathy to become radical empathy in the face of extreme situations of trauma, granted what that all means requires further clarification.

For Ruth Leys (2000) the distinction “trauma” itself is inherently unstable oscillating between historical trauma – what really happened, which, however, is hard if not impossible to access accurately – and, paradoxically, historical and literary language bearing witness by a failure of witnessing. The trauma events are “performed” in being written up as history or made the subject of an literary artwork. But the words, however authentic, true, or artistic, often seem inadequate, even fake. The “trauma” as brought forth as a distinction in language is ultimately inadequate to the pain and suffering that the survivor has endured, which “pain and suffering” (as Kant might say) are honored with the title of “the real.” Yet the literary or historical work is a performance that may give the survivor access to their experience.

The traumatic experience is transformed – even “transfigured” – without necessarily being made intelligible or sensible by reenacting the experience in words that are historical writing or drawing a picture (visual art) or dancing or writing a poem or bringing forth a literary masterpiece such as Beloved. The representational gesture – whether a history or a true story or fiction – starts the process of working through the trauma, enabling the survivor to reintegrate the trauma into life, getting power back over it, at least to the extent that s/he can go on being and becoming. In successful instances of working through, the reintegrated trauma becomes a resource to the survivor rather than a burden or (one might dare say) a cross to bear. To stay with the metaphor, the cross becomes an ornament hanging from a light chain of silver metal on one’s neck rather than the site of one’s ongoing torture and execution. Much work and working through is required to arrive at such an outcome.

Though Beloved has generated a vast amount of critical discussion, it has been little noted that the events in Belovedrapidly put the reader in the presence of moral trauma (also called “moral injury”). Though allusion was made above to the DSM, the devil is in the details. Two levels of trauma (and the resulting post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) are concisely distinguished (for example by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual(5th edition) of the American Psychiatric Association (2013). There is standard trauma – one survives a life changing railroad or auto accident and has nightmares and flashbacks (and a checklist of other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)). There is repeated trauma, trauma embedded in trauma, double-bind embedded in double bind. One is abused – and it happens multiple times over a course of months or years and, especially, it may happen before one has an abiding structure for cognition such as a stable acquisition of language (say to a two-year-old) or happens in such a way or such a degree that words are not available as the victim is blamed while being abused – resulting in complex trauma and the corresponding complex PTSD.

But this distinction, standard versus complex trauma (and the correlated PTSD), is inadequate in the case of moral trauma, where the person is both a survivor and a perpetrator.

Thus, an escaped slave makes it to freedom. One Margaret Garner is pursued and about to be apprehended under the Fugitive Slave Act. She tries to kill herself and her children rather than be returned to slavey. She succeeds in killing one of the girls. Now this soldier’s choice is completely different than the choice faced by Margaret/Sethe, and rather like the inverse of it, dependent on not enough information rather than a first-hand, all-too-knowledgeable acquaintance with the evils of enslavement from having survived it (so far). Yet the structural similarities are striking. Morrison says of Sethe/Margarent might also said of the soldier, “[…][S]he could do and survive things they believed she should neither do nor survive […]” (Morrison 1987: 67). Yet one significant difference between the soldier and Sethe (and the Jewish Zealots) is their answer to the question when human life ceases to be human. A casuistical clarification is in order. If human life is an unconditional good, then, when confronted with an irreversible loss of the humanness, life itself may not be an unconditional good. Life versus human life. The distinction dear to Stoic philosophy, that worse things exist than death, gets traction – worse things such as slavery, cowardice in the face of death, betraying one’s core integrity. The solder is no stoic; Sethe is. Yet both are suffering humanity.

However, one may object, even if one’s own human life may be put into play, it is a flat-out contradiction to improve the humanity of one’s children by ending their humanity. The events are so beyond making sense, yet one cannot stop oneself from trying to make sense of them. So far, we are engaged with the initial triggering event, the infanticide. No doubt a traumatic event; and arguably calling forth moral trauma. But what about trauma that is so traumatic, so pervasive, that it is the very form defining the person’s experiences. Trauma that it is not merely “unclaimed, split off” experience (as Caruth says). For example, the person who grows up in slavery – as did Sethe – has never known any other form of experience – this is just the way things are – things have always been that way – and one cannot imagine anything else (though some inevitably will and do). This is soul murder. So we have moral trauma in a context of soul murder. Soul murder is defined by Shengold (1989) as loss of the ability to love, though the individuals in Beloved retain that ability, however fragmented and imperfect it may be. Rather the proposal here is to expand the definition of soul murder to include the loss of the power spontaneously to begin something new – the loss of the possibility of possibility of the self, leaving the self without boundaries and without aliveness, vitality, an emotional and practical Zombie. In addition, as a medical professional, Shengold (1989) makes an important note: “Soul murder is a crime, not a diagnosis.” Though Morrison does not say so, and though she might or might not agree, enslavement is soul murder.

Beloved contains actual murders. Once again this is not for the fainto of heart. For example, Sethe’s friend and slave Sixo from the time of their mutual enslavement is about to be burned alive by the local vigilantes, and he gets the perpetrators to shoot him (and kill him) by singing in a loud, happy, annoying voice. He fakes “not givin’ a damn,” taking away the perpetrators’ enjoyment of his misery. It works well enough in the moment. His last. Nor is it like one murder is better (or worse) than another. However, in a pervasive context of soul murder, Sethe’s infanticide is an action taken by a person whose ability to choose -sometime called “agency” – is compromised by extreme powerlessness. Yet in that moment of decision her power is uncompromised by all the compromising circumstances and momentarily retored – whether for the better is that about which we are debating, bodly assuming the matter is debateable. One continues to try and justify and/or make sense out of what cannot have any sense. Sethe is presented with a choice (read it again – and again) that no one should have to make – that no one can make (even though the person makes the choice because doing nothing is also a choice). This is the same situation that the characters in classic Greek tragedy face, though a combination of information asymmetries, personal failings, and double-binds. Above all – double-binds. This is why tragedy was invented (which deserves further exploration, not engaged here).

Now bring empathy to moral trauma in the context of soul murder. Anyone out there in the reading audience experiencing “empathic unsettlement” (as LaCapra incisively put it)? Anyone experiencing empathic distress? If the reader is not, then that itself is concerning. “Empathic unsettlement” is made present in the reader’s experience by the powerful artistry deployed by Beloved. Yet this may be an instance in which empathy is best described, not as an on-off switch, but as a dial that one can dial up or down in the face of one’s own limitations and humanness. This is tough stuff, which deserves to be read and discussed. If one is starting to break out in a sweat, if one’s mouth is getting dry, if the pump in one’s chest is starting to accelerate its pumping, and one is thinking about putting the book down, rather than become hard-hearted, the coaching is temporarily to dial down one’s practice of empathy. While one is going to experience suffering and pain in reading about the suffering and pain of another, it will inevitably and by definition be a vicarious experience – a sample – a representation – a trace affect – not the overwhelming annihilation that would make one a survivor. Dial the empathy down in so far as a person can do that; don’t turn it off. Admittedly, this is easier said than done, but with practice, the practitioner gets expanded power over the practice of empathizing.

As noted, Morrison is a master of conversational implicature. Conversational implicature allows the empathy to get in – become present in the text and become present for the reader engaging with the text. The conversational implicature expresses and brings to presence the infanticide without describing the act itself by which the baby is killed. Less is more, though the matter is handled graphically enough. The results of the bloody deed are described – “a “woman holding a blood soaked child to her chest with one hand” (Morrison 1987: 124) – but not the bloody action of inflicting the fatal wound itself. “Writing the wound” sometimes dances artistically around expressing the wound, sometimes, not.

Returning to the story itself, Morrison describes the moment at which the authorities arrive to attempt to enforce the fugitive slave act: “When the four horsemen came – schoolteacher, one nephew, one slave catcher and a sheriff – the house on Bluestone Road was so quiet they thought they were too late” (Morrison 1987: 124). Conversational implicature meets intertextuality in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament. The four horsemen of the apocalypse herald the end of the world as we know it and the end of the world is what comes down on Sethe at this point. Perhaps not unlike the Zealots at Masada, she makes a fatal decision. Literally. As Hannah Arendt (1970) pointed out in a different political context, power and force (violence) stand in an inverse relation: when power is reduced to zero, then force – violence – comes forth. The slaves power is zero, if not a negative number. Though Sethe tries to kill all the children, she succeeds only in one instance. In the fictional account, the boys recover from their injuries and, in the case of Denver (Sethe’s daughter named after Amy Denver, the white girl who helped Sethe), Sethe’s hand is stayed at the last moment.

Beloved is a text rich in empathy. This includes exemplifications of empathy in the text, which in turn call forth empathy in the reader. The following discussion now joins the standard four aspects of standard empathy – empathic receptivity, empathic understanding, empathic interpretation, and empathic responsiveness. The challenge to the practice of empathy is that with a text and topic such as this one, does the practice of standard empathy need to be expanded, modified, or transformed from standard to radical empathy? What would that even mean? Empathy is empathy. A short definition of radical empathy is proposed: Empathy is committed to empathizing in the face of empathic distress, even if the latter is incurred, and empathy, even in breakdown, acknowledges the commitment to expanding empathy in the individual and the community.

We start with a straightforward example of empathic receptivity – affect matching. No radical empathy is required here. An example of standard empathic receptivity is provided in the text, and the dance between Denver and Beloved is performed (1987: 87 – 88):

“Beloved took Denver’s hand and place another on Denver’s shoulder. They danced then. Round and round the tiny room and it may have been dizziness, or feeling light and icy at once, that made Denver laugh so hard. A catching laugh that Beloved caught. The two of them, merry as kittens, swung to and fro, to and fro, until exhausted they sat on the floor. “

The contagious laughter is entry level empathic receptivity. Empathy degree zero, so to speak. This opening between the two leads to further intimate engagement with empathic possibility. But the possibility is blocked of further empathizing in the moment is blocked by a surprising discovery. At this point, Denver “gets it” – that Beloved is from the other side – she has died and come back – and Denver asks her, “What’s it like over there, where you were before?” But since she was killed as a baby, the answer is not very informative: “I’m small in that place. I’m like this here.” (1987: 88) Beloved, the person who returns to haunt the family, is the age she would have been had she lived.

The narrative skips in no particular order from empathic receptivity to empathic understanding. “Understanding” is used in the extended sense of understanding of possibilities for being in the world (e.g., Heidegger 1927: 188 (H148); 192 (H151)): “In the projecting of the understanding, beings [such as human beings] are disclosed in their possibility.” Empathic understanding is the understanding of possibility. What does the reader’s empathy make present as possible for the person in her or his life and circumstance? What is possible in slavery is being a beast of burden, pain, suffering, and early death – the possibility of no possibility of human flourishing. In contrast, when Paul D (a former slave who knew Sethe in enslavement) makes his way to the house of Sethe and Denver (and, unknown to him, the ghost of the baby), the possibility of family comes forth. In the story, there’s a carnival in town and Paul D, who knew Sethe before both managed to escape from the plantation (“Sweet Home”), takes her and Denver to the carnival. “Having a life” means many things. One of them is family. The possibility of family is made present in the text and the reader. That is the moment of empathic understanding of possibility:

“They were not holding hands, but their shadows were. Sethe looked to her left and all three of them were gliding over the dust hold hands. Maybe he [Paul D] was right. A life. Watching their hand-holding shadows [. . . ] because she could do and survive things they believed she should neither do nor survive [. . . .] [A]ll the time the three shadows that shot out of their feet to the left held hands. Nobody noticed but Sethe and she stopped looking after she decided that it was a good sign. A life. Could be.” (Morrison 1987: 67)

Within the story, Sethe has her own justification for her bloody deed. She is rendering her children safe and sending them on ahead to “the other side” where she will soon join them. “I took and put my babies where they’d be safe” (Morrison 1987: 193). The only problem with this argument, if there is a problem with it, is that it makes sense out of what she did. Most readers are likely to align with Paul D (a key character in the story and a “romantic” interest of Sethe’s), who at first does not know about the infanticide. Paul D learns the details of Sethe’s act from Stamp Paid, the person who is the former underground rail road coordinator, who knows just about everything that goes on, because he was a hub for the exchange of all-manner of information in helping run-away and would-be run-away slaves to survive.

Stamp feels that Paul D ought to know, though he later regrets his decision. Stamp tells Paul D about the infanticide – showing him the newspaper clipping as evidence and explaining the words that Paul D (who is illiterate) cannot read. Paul D is overwhelmed. He cannot handle it. He denies that the sketch (or photo) is Sethe, saying it does not look like her – the mouth does not match. Stamp tries to convince Paul D: “She ain’t crazy. She love those children. She was trying to out hurt the hurter” (1987: 276). Paul D asks Sethe about the infanticide reported in the news clipping, and she provides her justification (see above). Paul D is finally convinced that she did what she did, yet unconvinced it was the thing to do and a thunderhead of judgment issues the verdict: “You got two feet, Sethe, not four […] and right then a forest sprung up between them trackless and quiet” (1987: 194).[1] Paul D experiences something he cannot handle.

Standard empathy misfires as empathic distress. Standard empathy chokes on moral judgment. Paul D moves out of the house where he is living with Sethe, Denver, and Beloved. Standard empathy does not stretch into radical empathy. In a breakdown of empathic receptivity, Paul D takes on Sethe’s shame, and instead of a decision to talk about the matter with her, perhaps agreeing to exit the relationship for cause, Paul D runs away from both Sethe and his own emotional and moral conflicts, making an escape. Stamp blames himself for driving Paul D away by disclosing the infanticide to him (of which he had been unaware), and tries to go to explain it to Sethe. Seeking the honey of self-knowledge results in the stings of enraged distortion and disguise. Paul D finds the door is closed and locked against him. Relationships are in breakdown.

At this point the isolation of the women – Sethe, Denver, Beloved – inspires a kind of “mad scene” – or at least a carnival of emotion. Empathic interpretation occurs as dynamic and shifting points of view. The rapid-fire changing of perspectives occurs in the three sections beginning, “Beloved, she my daughter”; “Beloved is my sister”; “I am Beloved and she is mine” (Morrison 1987: 236; 242; 248). These express the hunger for relatedness, healing, and family that each of the women experience. For this reader, encountering the voices has the rhythmic effect of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. The voices are disembodied, though they address one another rather than the reader (as was also the case in Woolf). The first-person reflections slip and slide into a free verse poem of call and response. The rapid-fire, dynamic changing of perspectives results in the merger of the selves, which, strictly speaking, is a breakdown of empathic boundaries. There is no punctuation in the text of Beloved’s contribution to the back-and-forth, because Beloved is a phantom, albeit an embodied one, without the standard limits of boundaries in space/time such as are provided by standard punctuation.

This analysis has provided examples of empathic receptivity, understanding, and interpretation. One aspect of the process of empathy remains. In a flashback of empathic responsiveness: Sethe is on the run, having escaped enslavement at Sweet Home Plantation. She is far along in her pregnancy, alone, on foot, barefoot, and is nearly incapacitated by labor pains. A white girl comes along and they challenge one another. The white girl is named Amy Denver, though the reader does not learn that at first, and she is going to Boston (which becomes a running joke). What is not a joke is that Sethe and Amy Denver are two lost souls on the road of life if there ever were any. Amy is barely more safe or secure than Amy, though she has the distinct advantage that men with guns and dogs are not in hot pursuit of her. Sethe dissembles about her own name, telling Amy it is “Lu.” It is as if the Good Samaritan – in this case, Amy – had also been waylaid by robbers, only not beaten as badly as the man going up to Jerusalem, who is rescored by the Samaritan. Amy is good with sick people, as she notes, and practices her arts on Sethe/Lu. Sethe/Lu is flat on her back and in attempt to help her stand up, Amy massages her feet. But Sethe/Lu’s back hurts. In a moment of empathic responsiveness, Amy describes to Sethe/Lu the state of her (Sethe’s) back, which has endured a whipping with a raw hide whip shortly before the plan to escape was executed. Amy tells her:

“It’s a tree, Lu. A chokecherry tree. See, here’s the trunk – it’s red and spit wide open, full of sap, and this here’s the parting for the branches. You got a mighty lot of branches. Leaves, too, look like, and dern if these ain’t blossoms. Tiny little cherry blossoms, just as white. Your back got a whole tree on it. In bloom. What god have in mind I wonder, I had me some whippings, but I don’t remember nothing like this” (1987: 93).