Home » empathy

Category Archives: empathy

Top ten trends in empathy for 2025

The idea is to take a position from the perspective of empathy on current trends. What would the empathic response be to the trend in question, especially crises and breakdowns.

1. The world is filled with survivors who are perpetrators (and vice versa). Radical empathy is needed to relate to survivors who are also perpetrators. Radical empathy is the number one trend. What does that mean? The world is a more dangerous, broken place than it was a year ago. The challenge to empathy is that the dangers and breakdowns in the world have expanded dramatically over the long past year such. Standard empathy is no longer sufficient. Radical empathy is required.

Image credit: Jan Steen, 1665, As the old sing, so pipe the young

The short definition of radical empathy: the events that occur are so difficult, complex, and traumatic that standard empathy breaks down into empathic distress and fails. In contrast, with radical empathy, empathic distress occurs, but one’s commitment to the other person is such that one empathizes in the face of empathic distress. One’s empathic commitment to the survivor enables the survivor to recover her/his humanness, integrity, and relatedness. The work of radical empathy engages how the impact and cost of empathic distress affect the different aspects of empathic receptivity, empathic understanding, empathic interpretation, and empathic responsiveness, delivering a breakthrough and transformation in relating to the Other.

An example will be useful. A US soldier gets up in the morning. He is an ordinary GI Joe. He is manning a checkpoint. The sergeant, thinking the approaching car is a car bomb, gives what he believes is a valid military order to shoot at the car. The solider shoots. The car stops. But it was not a car bomb; it was a family rushing to the hospital because the would-be mother (now deceased) was in labor. The military debriefing of the events is perfunctory. Burdened by guilt, the soldier shuts down emotionally, and he stares vacantly ahead into space. Emotionally gutted, he does not respond to orders. He is shipped back to the States and dishonorably discharged. His marriage fails. He becomes homeless. The point? This person is now both a perpetrator and a survivor. The people who were shot experienced trauma by penetrating wounds. The soldier has moral trauma. Key term: moral trauma. He was put in an impossible situation; damned if he did and damned if he didn’t. Let his team be blown up? Disobey what seems to be a valid military order? Hurt people who did not need or deserve to get hurt? His ability to act, his agency, was compromised by being put in an impossible situation. That is why the ancient Greeks invented tragic theatre – except that the double binds happen every day. Radical empathy specializes in empathizing with those who are both survivors and perpetrators. And this is much more common than is generally realized.

Many examples of radical empathy can be found in literature (or in the New York Times), in which the hero or anti-hero of the story is caught in a double bind, damned if one does and damned if one doesn’t. Radical empathy and the literary artwork transfigure the face of trauma, overcoming empathic distress, and allowing radical empathy to enable the fragmented Other to recover her/his integrity. Persons require radical empathy to relate to, process, and overcome bad things happening to good people (for example: moral and physical trauma, double binds, soul murder, and behavior in extreme situations. For further reding on radical empathy, see the book of the same title in the References below.

2. No human being is illegal. Mass deportations pending. Empathy, whether standard or radical, is clear on this trend: no human being is illegal. At the same time, the empathy lesson is acknowledged that empathy is all about firm boundaries and limits between the self and other, while allowing for communications between the two. It is the breakdown of empathy at the US national border – which does not mean wide open borders – is one reason among several for the result of the 2024 election. What if ICE agents (the immigration authorities) show up? Empathy is all about setting boundaries: The empathic response: Let’s see your judicial warrant, officer, please? (See The New York Times, Dana Goldstein, Jan 7, 2025: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/07/us/immigration-deportations-ice-schools.html.)

An empathic response would look like a workable Guest Worker Program (such as exist in the European union) that allows essential agricultural and food services workers to earn and send money back home. Yet the proverbial devil is in the detail, and being accused of the crime of shop lifting a sandwich or tube of toothpaste is different than actually committing one. Thus, empathy also looks like Due Process, and an opportunity to face one’s accuser. If one is standing outside a Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s begging for food, it is not because one’s life is going so well. The gesture that any decent customer would make is to buy the person a sandwich. Of course, that is not going to scale up to address the estimated 37 million Americans (the majority not recent immigrants) living in poverty. Continued below under “5. The unworthy poor.”

3. Psychiatry gets empathy (ongoing). Relate to the human being in front of you, not the diagnosis. Empathy teaches de-escalation. Empathy’s coaching to psychiatry as a profession is to do precisely that which psychiatry is least inclined to do, namely, relate to the human being in front of you, not to a diagnosis.

Granted, the human being is a biological system. We are neurons all the way down. Yet emergent properties of our humanity (including empathy) come forth from the proper functioning of the neurons. The neurons generate consciousness, that subtle awareness of our environment that we humans share with other mammals. Consciousness generates relatedness to the environment and one another. Relatedness generates meaning. Meaning generates language. Language generates community, society, and culture. As Dorothy is reported to have said to Toto, “We are no longer in Kansas” – or psychiatry.

So what’s the recommendation from the point of view of empathy? Relate to the human being sitting in front of you not to a diagnosis. That is the empathic moment. To be sure, a diagnosis has its uses in technical communications with colleagues or payers, but as a standalone label, diagnoses are overrated.

Taking a step back, people get into psychiatry (and medicine in general) because they want to relieve pain and suffering, because they want to make a difference. Yet this aspiration is in stark contrast with the report at the American Psychiatric Association meeting that physical restraints were used some 44,000 times last year to constrain patients. (See Ellen Barry, May 21, 2024 In the house of psychiatry, a jarring tale of violence. Thus, The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/21/health/psychiatric-restraint-forced-medication.html)

“Don’t hurt yourself (or anyone else!)!” is solid guidance; yet the particulars of the situation are challenging. The distance between fight and flight (fear) is narrow. Someone in the throes of an “amygdala hijack” is in an altered state of consciousness. This person literally cannot hear what is being said to him or her. This person is at risk of precipitating a bad outcome, especially if the psychiatrist or staff is also hijacked by an emotional reaction and emotional contagion. If as much effort were devoted to training staff in verbal escalation – talking someone back “off the ledge” – as in training them synch up straps, the outcomes would be less traumatic for all involved. Empathy in all its forms is a basic de-escalation skill that needs to receive expanded training and development.

It would not be fair to confront a psychiatrist with an either/or: “Are you relating to a biological system or to a human being?” because she (or he) is relating to both. Yet the pendulum does seem to have swung too far in the direction of biochemical mechanisms rather than interpersonal meaning, relations, and fulfilment. It is a fact that some 80% of people visit the medical doctor because they are in pain and hope to get medicine to cause them to feel better (and the other 20% have scheduled an annual checkup). That is well and good; and it is true that these psychopharm medicines change the neurons in your brain, but so does studying French and so do new and engaging life experiences; and, here’s the point, so does the committed application of empathy.

3. Violence against women continues to be a plague upon the land and a challenge to empathy.Standard empathy is not enough. This requires a level of radical empathy that has not been much appreciated. This is because many perpetrators are also survivors. (See the above example of the ordinary soldier who becomes both.)

I hasten to add that two wrongs do not make a right. Two wrongs make twice the wrong. Intervention is required to get the woman safe, and recovery from domestic violence begins once the person is secure in their safety. That is not a trivial matter, and Safety Plans and Hot Lines continue to be important resources. One can incarcerate a perpetrator to protect the community (and the women in it), but that does not make him better. He still needs treatment. What are the chances he is going to get it? To cut to the chase: many perpetrators and survivors do not know what a satisfying, healthy relationship looks like. Survivors and perpetrators alike have come up in environments where physical violence is common. Once again, this is not an excuse, and two wrongs do not make a right.

Regarding Peter Hegserth (Cabinet nominee for Defense Secretary): NBC News has reported that Mr. Hegseth’s heavy drinking concerned co-workers at Fox News and that two of them said they smelled alcohol on him more than a dozen times before he went on the air. The New Yorker reported: “A trail of documents, corroborated by the accounts of former colleagues, indicates that Hegseth was forced to step down by both of the two nonprofit advocacy groups that he ran — Veterans for Freedom and Concerned Veterans for America — in the face of serious allegations of financial mismanagement, sexual impropriety, and personal misconduct.” His managerial skills are nowhere near the challenge of running the Pentagon. Meanwhile, according to a 2018 email obtained by the New York Times, Mr. Hegseth’s own mother called him “an abuser of women” as he went through his second divorce. It is particularly concerning to see Senator Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) who had a check box on Domestic violence on her official site accept/excuse/embrace such behavior. Among the many women serving in the US Armed Forces, who can imagine that this candidate has their back? The esteemed Senator Ernst may usefully her from the concerned citizens.

The number one empathy lesson: a grownup man having temper tantrums (and worse) is not what a healthy relationship looks like! In a healthy relationship partners cooperate, help one another, respect boundaries, and if they disagree, they argue and “fight” fairly. Skills training belongs here. A major skill: setting boundaries, limits – pushing back on bullying in all its forms. (In addition, parents of diverse backgrounds and cultures have got to find better ways to set limits to and for their children than “whupping ‘em.”)

Woman have provided the leadership in this struggle for domestic tranquility and will continue to do so. From men’s perspective, this is a failure not only of standard empathy, but a failure of leadership. It calls for radical empathy to include survivors and perpetrates (once again, without making excuses for bad behavior). When powerful men – President Biden (now retiring), Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Senators and captains of industry – step up and say “Enough! What are you thinkin’, man?” then the issue will get transformed. These are conversations that are best had by men with men. Even if that sounds sexist, it makes a difference when a man tells another man that his behavior towards women or a woman is out of line and requires correction rather than when a woman says it (though it is equally true in both cases). Even though Jackson Katz’s video has been around for several years, it has never been better expressed: “Violence against women: It’s a men’s problem”: https://youtu.be/ElJxUVJ8blw?si=k8LG0ewnL6ZKlgt9. Please circulate widely.

4. “Abandon reality all ye who enter here!” is inscribed over the sign-in to Facebook. “Facts are overrated.” Yet a rigorous and critical empathy knows that it can be wrong so it is committed to distinguishing facts from fictions. Empathy was never particularly concerned with the reasons why you are in pain, but how to relieve that pain. The corporation Meta (owner of Facebook (FB)) decides to end fact checking regarding posts on its social networking site (https://www.nytimes.com/live/2025/01/07/business/meta-fact-checking). It is hard not to be cynical at this moment.

Many people know “empathy for everyone” is a pipe dream; yet there is no other way to bring it into the world than to work to make it real. The human imagination is a possibility engine, and it is the source of what is possible in the human relations defined by empathy. If the “crazy ideas” on Facebook (and elsewhere) were just that, crazy idea, they might actually be useful in terms of “brain storming.”. However, when non facts such as immigrants are stealing and eating your pets are represented as occurring events in the world, the damage to the community is significant.

This is when radical empathy as “Red Team! Red Team!” comes in (see the references Zenko 2015). Think like the opponent. Take the opponent’s point of view, not to agree or disagree with him; but to get one’s power back over delusional thinking. Prejudice against individuals and groups has many sources – largely projection of one’s own fears and blind spots onto the devalued Other. However, ultimately prejudice is a form of mental illness – delusional thinking – at the community level. From an empathic perspective, FB becomes a site of delusional thinking, noting that even a broken clock gives the correct time twice a day. By the way, the original Pizza-Gate conspirator, who, living in a persistent altered state of consciousness, claimed a popular local pizza parlor was really a nest of satanic pedophilia, was shot and killed by police on January 4, 2025 when he raised a gun during a police traffic stop. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2025/01/09/edgar-maddison-welch-pizzagate-killed/ Case closed. He was the father of two daughters. Tragically misinformed. Unnecessary. Fact checking saves lives!

5. Help for the unworthy poor. Empathy says the worthy poor need help; but radical empathy asserts that the unworthy poor need even more help(and who is deciding who is “worthy” anyway? See above under “no human being is illegal”).

In a highly entertaining, albeit sexist retelling of the myth of Pygmalion, My Fair Lady – the alcoholic, unemployed father (Alfred) of Liza Doolittle confronts Professor Higgins with a request for money for his permission to subject his daughter to the enculturing “make over” of improving her language that is the main project of the plot. In a comic yet thought-provoking scene, the father notes that many people of means are making financial contributions to help the struggling, worthy impoverished (“the poor”); but who is helping the unworthy poor?! “I don’t deserve the handout. I am lazy and a drunk (in so many words); but give me ten pounds sterling anyway.” An admirably direct argument and not without a certain integrity. Yet if one grew up in poverty and even if the parent was not “whuppin’” everyone in sight or engaging with substances of abuse and neglecting basic education, then high probability one will satisfy the definition of “unworthy poor” – no (limited) motivation to pull oneself up by one’s bootstraps. Yes, by all means, government needs to expand its efficiency and effectiveness, but this might not be an efficient process. Line up and with help from a bureaucrat (which used to mean simply “helpful office holder,” not “unempathic jerk”) fill out the forms. However, one cannot give people money; or rather the risk of doing so is that it is not going to make a difference. Educational vouchers? Financial skills training? Parental training? Food vouchers? Rental vouchers? Food, rent, and education.

Guilt trip, anyone? The rich get richer; the poor get – older. The devil’s advocate says the poor should work harder to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Empathy says that the devil already has too many advocates. A tax on billionaires’ net worth would generate enough funds in five years to reduce the number of people living in poverty (estimated to be some 37 million as of 2023) by 80%. Radical empathy is required!

6. Empathy is part of the mission of health insurance, not more monopoly rents to insurance corporations. The economics of health insurance are compelling – get everyone into the insurance pool and spread the risk. Risk that is spread is risk contained, managed, and conquered. It is a pathology of capitalism that competition does not function as designed in the matter of such common goods as clean water, clean air, and conditions necessary to health and well-being such as access to medical treatments Healthcare corporations are incented by competition to get rid of sick people (do not do business with them) since sick people reduce profits, even though sickness is why the insurance came into existence. This is madness! And this is why intervention of the federal authorities (and legislation) was needed to prevent corporations from excluding the pre-existing conditions (illnesses). Therefore, the trend is to make empathy a part of the mission of insuring healthcare.

For example, there is an innovative medicine to treat schizophrenia that does not have as many of the undesired, troubling, painful side effects such as tardive dyskinesis of current medicines. However, out of the gate, it costs $1800 a month, and for pharmaceutical companies properly to recoup the staggering costs of development – what are the chances that insurance companies will cover it? Don’t hold your breath. According to the FDA News release about 1% of Americans have this illness and it is responsible for some 20% of disability claims. Think of the benefits for suffering, struggling survivors of this disease. Think of the cost reducing impact of an effective treatment on the federal budget. (For further background see:

7. Radical empathy contradicts the delusional belief that people committed to a suicide mission are going to yield to threats of violence. This theme, which is ongoing from last year, is yet another case for “Red Team! Red Team!” Think like the opponent – which may include thinking like the enemy. This grim empathy lesson was expressed by Fionnuala D. Ní Aoláin (Oct 13, 2023) during Q&A in her talk, “The Triumph of Counter-Terrorism and the Despair of Human Rights” at the University of Chicago Law School. Professor Aoláin draws on the example of the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, The Troubles, between 1960 and 1998’s Good Friday Agreement. On background, this had all the characteristics of intractable hatred, perpetrations and human rights violations, the British government making every imaginable mistake, the Jan 30, 1972 shooting of 26 unarmed civilians by elite British soldiers, internment without trail, members of the Royal Family (Louis Mountbatten, the Last Viceroy of India, and his teenage grandson (27 Aug 1979)) blown up by an IRA bomb, the IRA (Irish Republican Army) launching a mortar at 10 Downing Street (no politicians were hurt, only innocent by-standers), and many tit-for-tat acts of revenge killing of innocent civilians. It is hard, if not impossible, to generalize as every intractable conflict is its own version of hell—no one listens to the suffering humanity—but what was called The Peace Process got traction as all sides in the conflict became exhausted by the killing and committed to moving forward with negotiations in spite of interruptions of the pauses in fighting in order to attain a sustainable cease fire.

The relevance to ongoing events in the Middle East will be obvious. An organization widely designated in the West as “terrorist” changes the course of history in the Middle East. Hearts are hardened by the boundary violations, atrocities, and killings. The perpetrators lead their people off a cliff into the abyss, and the survivors of the attack defend themselves vigorously and properly, and then, under one plausible redescription, themselves become perpetrators, launching themselves off the cliff, following the perpetrators into the abyss, the bottom of which is not yet in sight. Survivors and perpetrators one and all call for and call forth radical empathy. Negotiate with the people who have killed your family. Empathize with that.

The response requires radical empathy: to empathize in the face of empathic distress, exhausted by all the killing. Though neither the didactic trial in Jerusalem (1961) of Holocaust architect Adolph Eichmann nor the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (1995) lived up to their full potentials, they formed parts of processes that presented alternatives to violence and extra judicial revenge killings. In this frame, the survivor is willing to judge if the perpetrator is speaking the truth and expressing what, if any, forgiveness is possible. The radical empathy that empathizes in the face of empathic distress acknowledges that moral trauma includes survivors who are also perpetrators (and vice versa). (See Tutu 1997 in the References for further details.) In a masterpiece of studied ambiguity, radical empathy teaches that two wrongs never make a right; they make at least twice the wrong; and one who sews the wind reaps the whirlwind.

8. Empathy and climate change: you better start swimming or you’ll sink like a stone. Scientists describe global warming as a “wicked problem,” in the sense that so many variables are changing across so many scenarios that it is wicked hard—if not impossible—to conduct a controlled experiment. The readers of this article “know” the planet is warming. This is not just information, but heatstroke, a hurricane blowing the roof off of one’s house, catastrophic fires encroaching on cities, and disastrous flooding. Parts of the planet are becoming uninhabitable by humans because of extreme heat, hurricanes, and rising seas, which are indeed data, but not merely data as these events are lethal to human life. If wetlands, reservoirs, agricultural lands, landfill, tundra, are releasing methane (one of the major “greenhouse gases” contributing to global warming) in rapidly accelerating volumes, faster than ever, one may argue, an even greater effort should be exerted to curb methane from the sources humans can control, like cows, agriculture and fossil fuels (Osaka 2024). Yet what seems obvious in New York City or Chicago does not even get a listening in the mountains of Idaho much less the overcrowded cities of China, India, or Russia. The probable almost certain future comes into view, and there is about as much chance of this trend spontaneously reversing itself as that the San-Ti are going to arrive at light speed from Alpha Centauri and tell earth people how to fix it. What is amazing is that Bob Dylan’s example of rhetorical empathy has been available in his poetry and song since 1965 when, coincidently and on background, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, Medicaid, into law, and “surged” half a million US soldiers into DaNang, Vietnam. Transformation is at hand, though it requires further parsing. Thus, Dylan’s proposed rhetorical empathy (1965: 81):

Come gather ‘round people / Wherever you roam / And admit that the waters / Around you have grown / And accept it that soon / You’ll be drenched to the bone / If your time to you is worth savin’ / Then you better start swimmin’ or you’ll sink like a stone / For the times they are a-changin’

The relevance of empathy should never be underestimated, and empathy as such is not going to staunch this flood. Nor is empathy going to solve “highly polarized social and political world,” unless citizens of plural persuasions, parties, and global geographies, who have stopped listening to opposing points of view, are willing to start listening to one another again. Key term: willingness. Everyone can think of a person (in-person or on TV) whose opinions—whether cultural, political, or cinematic—really drives one to distraction? That’s the person one should be asking out for a cup of coffee—not to try to persuade her or him, but to listen. The situation is so bad, that most people no longer associate with people with whom they disagree, so they can’t follow this simple recommendation. How then, in the face of such, obstacles is one going to use empathic practices to move the dial (so to speak) in the direction of such reduced polarization and expanded community? This leads to the next trend.

9. Rhetorical empathy is trending: the relationship between empathy and rhetoric has not been much appreciated or discussed – until now! Empathy and rhetoric seem to be at cross purposes. With empathy one’s commitment is to listen to the other individual in a space of acceptance and tolerance to create a clearing for possibilities of overcoming and flourishing. With rhetoric, the approach is to bring forth a persuasive discourse in the interest of enabling the Other to see a possibility for the individual or the community. At the risk of over- simplification, empathy is supposed to be about listening, receiving the inbound message; whereas rhetoric is usually regarded as being about speaking, bringing forth, expressing, and communicating the outbound message. Once again, in the case of empathy, the initial direction of the communication is inbound, in the case of rhetoric, outbound. Yet the practices of empathy and rhetoric are not as far apart as may at first seem to be the case, and it would not be surprising if the apparent contrary directionality turned out to be a loop, in which the arts of empathy and rhetoric reciprocally enabled different aspects of authentic relatedness, community building, and empowering communications.

In rhetorical empathy, the speaker’s words address the listening of the audience in such a way as to leave the audience with the experience of having been heard. As noted, this must seem counter-intuitive since it is the audience that is doing the listening. The hidden variable is that the speaker knows the audience in the sense that she or he has walked a mile in their shoes (after having taken off her/his own), knows where the shoes pinch (so to speak), and can articulate the experience the audience is implicitly harboring in their hearts yet have been unable to express. The paradox is resolved as the distinction between the self and Other, the speaker and the listener, is bridged and a way of speaking that incorporates the Other’s listening into one’s speaking is brought forth and expressed. Rhetorical empathy is a way of speaking that incorporates the Other’s listening into one’s speaking in such a way that the Other is able to hear what is being said. (For further reading see Blankenship 2019; Agosta 2024b.)

10. Empathy becomes [already is] an essential aspect of critical thinking. Teach critical thinking. Critical thinking includes putting oneself in the place of one’s opponent—not necessarily to agree with the other individual—but to consider what advantages and disadvantages are included in the opponent’s position. Taking a walk in the Other’s shoes after having taken off one’s own (to avoid the risk of projection) shows one where the shoe pinches. This “pinching” —to stay with the metaphor—is not mere knowledge but a basic inquiry into what the other person considers possible based on how the other’s world is disclosed experientially. This points to critical thinking as an inquiry into possibility—possible for the individual, the Other, and the community. Critical thinking is a possibility pump designed to get people to start again listening to one another, allowing the empathic receptivity (listening) to come forth.

In our day and age of fake news, deep fake identity theft, not to mention common political propaganda, one arguably needs a course in critical thinking (e.g., Mill 1859; Haber 2020) to distinguish fact and fiction. Nevertheless, I boldly assert that most people, who are not suffering from delusional disorder or political pathologies of being The True Believer (Hoffer 1953)), are generally able to make this distinction. A rigorous and critical empathy creates a safe zone of acceptance and tolerance within which people can inquire into what is possible—debate and listen to a wide spectrum of ideas, positions, feelings, and expressions out of which new possibilities can come forth.

For example, empathy and critical thinking support maintaining firm boundaries and limits against actors who would misuse social media to amplify and distort communications. Much of what Jürgen Habermas (1984) says about the communicative distortions in mass media, television, and film applies with a multiplicative effect to the problematic, if not toxic, politics occurring on the Internet and social networking. The extension to issues of climate change follows immediately. Insofar as individuals skeptical of empathy are trying to force a decision between critical thinking and empathy, the choice must be declined. Both empathy and critical thinking are needed; hence, a rigorous and critical empathy is included in the definition of enlarged, critical thinking (and vice versa). (Note that “critical thinking” can mean a lot of things. Here key references include John Stuart Mill 1859; Haber 2020; “enlarged thinking” in Kant 1791/93 (AA 159); Arendt 1968: 9; Habermas 1984; Agosta 2024.)

In particular, critical thinking encompasses what the poet John Keats (1817) called “Negative Capability.” It enables one to dance in the chaos of the dynamic stresses, struggles, and successes one encounters: “I mean [. . .] when a man [person] is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Such Negative Capability is a synonym of and a bridge to empathizing in the broad sense. Giving up certainty enables empathy and critical thinking to establish and maintain a safe zone of acceptance and tolerance for conversation, debate, self-expression. The sinking or swimming that the other poet, Dylan, proposes points to many things (including getting involved), yet it is most of all critical thinking. This is the space of inquiry—of asking what is possible—brainstorming—and calling forth projects and action. This results in a rigorous and critical empathy, nor going forward should any committed empathy advocate refer to empathy in any other way. (For further reading on Rhetorical Empathy see the article listed in the endnotes “Rhetorical empathy in the context of ontology.”)

The poet gets the last example of rhetorical empathy. One has to push off the shore of certainty and venture forth into the unknown possibilities of radical empathy. Bob Dylan (1965: 185) interrupted his climate change advocacy to become an empathy enthusiast. Dylan gets the last word: “I wish that for just one time / You could stand inside my shoes / And just for that one moment / I could be you” [.]

References

Agosta, Lou. (2024). Empathy Lessons. 2nd Edition. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

Arendt, Hannah. (1952/1958). The Origins of Totalitarianism, 2nd Edition. Cleveland and New York: Meridian (World) Publishing, 1958.

__________. (2024b) “Rhetorical empathy in the context of ontology,” Turning Toward Being: The Journal of Ontological Inquiry in Education: Vol. 2: Issue 1, Article 5.

Available at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/joie/vol2/iss1/5

__________. (due out May 2025). Radical Empathy in the Context of Literature. New York: Palgrave Publishing. https://books.google.com/books/about/Radical_Empathy_in_the_Context_of_Litera.html?id=qdDk0AEACAAJ The book does not merely tell the reader about radical empathy in the context of the literary art work; it delivers an experience of radical empathy in context in empathy’s receptivity, understanding, interpretation and responsiveness.

Arendt, Hannah. (1952/1958). The Origins of Totalitarianism, 2nd Edition. Cleveland and New York: Meridian (World) Publishing, 1958.

________________. (1968). Men in Dark Times. New York: Harvest Book (Harcourt Brace).

Blankenship, Lisa. (2019). Changing the Subject: A Theory of Rhetorical Empathy. Logan UT: Utah State University Press.

Dylan, Bob. (1965). Bob Dylan: The Lyrics: 1961–2012. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Haber, Jonathan. (2020). Critical Thinking. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Habermas, Jürgen. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action, Vol 1, Thomas McCarthy (tr.). Boston: Beacon Press.

Kant, Immanuel. (1791/93). Critique of the Power of Judgment, Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews (trs.). Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013.

Keats, John. (1817). Letter to brothers of December 21, 1817: https://mason.gmu.edu/~rnanian/Keats-NegativeCapability.html [checked on 10/15/2024].

Mill, John Stuart. (1978: 1859). On Liberty, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Desmond, Tutu. (1997). No Future Without Forgiveness. New York: Random House.

Zenko, Micah. (2015). Red Team: How to Succeed by Thinking Like the Enemy. New York: Basic Books.

© Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Paul Ricoeur, Philosopher of Empathy

This article on Paul Ricoeur, empathy, and the hermeneutics of suspicion in literature will be engaging to students of Ricoeur and empathy alike. One can download the PDF directly from the journal Etudes Ricœeurienne / Ricoeur Studies website: http://ricoeur.pitt.edu/ojs/ricoeur/article/view/628

The article is in English and an abstract is cited below at the bottom. If the above link does not work for any reason, then scroll to the bottom, where one can download the PDF within this blog post.

Meanwhile, I offer a recollection of my personal encounter with Professor Ricœur starting when I was a third year undergraduate at the UChicago. (This is an excerpt from a pending manuscript on empathy in the context of literature.)

By the time I was an undergraduate in my junior year in college, Paul Ricoeur had just arrived at the University of Chicago. Professor Ricoeur had attempted to play a conciliatory role in listening to and addressing student grievances in the face of entrenched method of lecturing by ex cathedra by mandarin professors at the Sorbonne, Paris, France, and related schools in the system. Though Ricoeur did not use the word “empathy” in his role as administrator at the University of Nanterre, he was attempting to play a role in conflict mediation, during the strike of student and workers in Paris in May 1968, a role in which empathy is famously on the critical path.

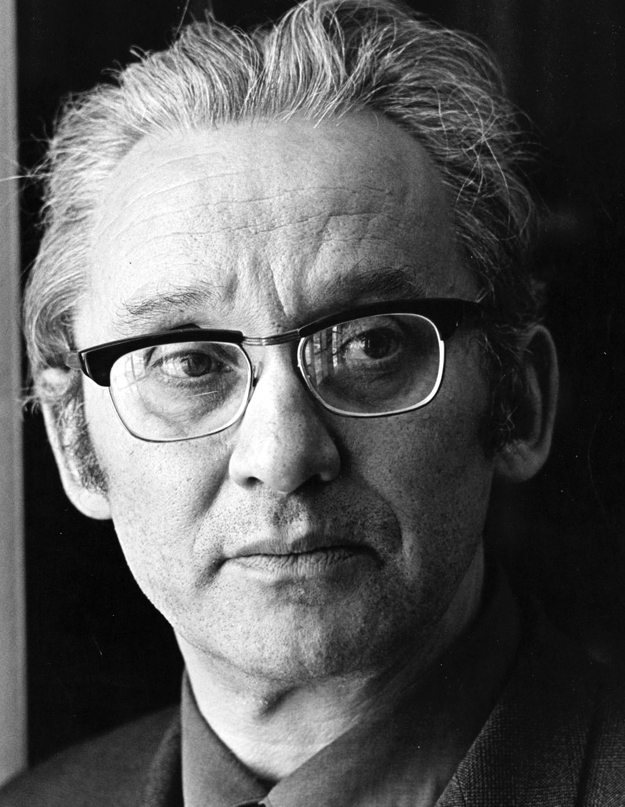

[Photo: Paul Ricoeur, circa 1970 upon his arrival at the University of Chicago, looking for all the world like the Hollywood icon, James Dean. University of Chicago News office: Detailed photo credit below.]

Ricœur’s intervention in the dynamics of academic politics and expanding the community of scholars the way he had done in setting up a kind of philosophy university in the German prisoner of war camp for his fellow French prisoners in 1941 did not work as well as he had hoped. Though it would not be fair to anyone (or to be taken out of context), the Germans (at that moment) were less violent than the striking French students and Peugeot workers in 1968. The French students threw tomatoes at Ricœur and called him a “old clown”; whereas the University of Chicago “threw” at him a prestigious named professorship. He liked the latter better. Ricœur’s courses were open to undergraduates who got permission, too, so I signed up for two of them – Hermeneutics and The Religious Philosophies of Kant / Hegel. Insert here a mind-bending blur of hundreds of pages of reading interspersed with dynamic and engaging presentations of the material. After the somewhat softball oral exams, for which he charitably gave me a pass, my head was spinning, and I needed to take a year off from school to regroup. I am not making this up. I worked as a parking lot attendant selling parking passes, which was an ideal job, since I could read a lot—you know, German-English facing pagination of two separate philosophical texts. This interruption also gave me time to go out for theatre to work on overcoming my painful social awkwardness and try and get a date with a girl. This “therapy” worked well enough, though, like most socially inept undergraduates, I had no skill at small talk and tended to utter what I had to say out of the blue and without creating any context. When I returned to school the next year to finish up, I proposed doing a bachelor’s thesis on Kant’s Refutation of Idealism, and I went into Professor Ricoeur’s office to make my proposal. Ricoeur was team teaching “Myth and Symbolism” with Mircea Eliade, and the “Imagination and Kant’s Third Critique” with Ted Cohen. Without any introductory remarks—I don’t think I even said my name—I presented the idea for my bachelor’s thesis. Without further chit-chit, raising one finger in the air for emphasis and smiling broadly, the first thing he said to me was: “An internal temporal flux implies an external spatial permanence.” With the benefit of 20-20 hindsight, I consider this a suitably empathic response, albeit an unconventional one. My paper eventually got published in the proceedings of the Acts of the 5th International Kant Congress. Fast forward a couple of years, comprehensive written exams in philosophy, and I proposed to write a PhD dissertation in philosophy on empathy [Einfühlung] and interpretation. Max Scheler’s Essence and Forms of Feelings of Sympathy [Wesen und Formen der Sympathiegefühl] contains significant material on empathy, and is (arguably) an early version of C. Daniel Batson’s collection of empathically-related phenomena. I was reading it with Professor Ricœur. Meanwhile, a psychoanalysis named Heinz Kohut, MD, like so many, a refugee from the Nazis, was innovating in empathy in the context of what was to become Self Psychology. I told one of the faculty at the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis who was a mentor to me (and a colleague of Kohut), Arnold Goldberg, MD, about Ricœur’s Freud and Philosophy. Whether at my instigation or on Dr Goldberg’s own initiative (Ricoeur really needed no introduction from me), Dr Goldberg introduced Professor Ricoeur to the editors at the Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association (JAPA) and the result was Ricœur’s publication “The Question of Proof In Freud’s Psychoanalytic Writings” in JAPA August 1977 [Volume 25, Issue 4 6517702500404]. Using graduate students as a good occasion for a conversation to build relationships, we all then had dinner at the Casbah, a middle eastern restaurant on Diversey near Seminary Avenues in Chicago’s Old Town.

It always seemed to me that Professor Ricoeur was a teacher of incomparable empathy, though he rarely used the word, at least until I started working on my dissertation on the subject of empathy and interpretation. I am pleased, indeed honored, to be able to elaborate the case here, while also defending Ricœur’s hermeneutics of suspicion from a misunderstanding that has shadowed the term since Toril Moi’s discussion (2017) of it at the University of Chicago colloquium on the topic shortly before the pandemic, the details of which are recounted in the article.

ricouerempathyinthecontextofsuspicionDownload

ABSTRACT: This essay defends Paul Ricoeur’s hermeneutics of suspicion against Toril Moi’s debunking of it as a misguided interpretation of the practice of critical inquiry, and we relate the practice of a rigorous and critical empathy to the hermeneutics of suspicion. For Ricoeur, empathy would not be a mere psychological mechanism by which one subject transiently identifies with another, but the ontological presence of the self with the Other as a way of being —listening as a human action that is a fundamental way of being with the Other in which “hermeneutics can stand on the authority of the resources of past ontologies.” In a rational reconstruction of what a Ricoeur-friendly approach to empathy would entail, a logical space can be made for empathy to avoid the epistemological paradoxes of Husserl and the ethical enthusiasms of Levinas. How this reconstruction of empathy would apply to empathic understanding, empathic responsiveness, empathic interpretation, and empathic receptivity is elaborated from a Ricoeurian perspective.

Photo credit: University of Chicago Photographic Archive, [apf digital item number, e.g., apf12345], Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

This blog post and web site (c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Protected: In the beginning was the word – empathy!

Subscribe to continue reading

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Historical empathy, guns, and the strict construction of the US Constitution

I am sick at heart. This is hard stuff. All those kids. Teachers and principals, too, dying trying to defend the children. Everyone cute as button. Just as bad, I have to re-publish this article, since the needed breakthrough has not yet occurred. What to do about it? My proposal is to expand historical empathy. Really. Historical empathy is missing, and if we get some, expand it, something significant will shift.

Putting ourselves in the situation of people who lived years ago in a different historical place and time is a challenge to our empathy. It requires historical empathy. How do we get “our heads around” a world that was fundamentally different than our own? It is time – past time – to expand our historical empathy (Kohut 2020). For example …

Brown Bess, Single Shot Musket, standard with the British Army and American Colonies 1787

When the framers of the US Constitution developed the Bill of Rights, the “arms” named in the Second Amendment’s “right to keep and bear arms” referred to a single shot musket using black powder and lead ball as a bullet. The intention of the authors was to use such weapons for hunting, self-defense, arming the nascent US Armed Forces, and so on. No problem there. All the purposes are valid and lawful.

One thing is for sure and my historical empathy strongly indicates: Whatever the Founding Fathers intended with the Second Amendment, they did NOT intend: Sandy Hook. They did not intend Uvalde, Parkland, Columbine, Buffalo, NY, Tops Friendly. They did not intend some 119 school shootings since 2018. They did not intend a “a fair fight” between bad guys with automatic weapons and police with automatic weapons. The Founding Fathers did not intend wiping out a 4th grade class using automatic weapon(s). They did not intend heart breaking murder of innocent people, including children, everyone as cute as a button.

Now take a step back. I believe we should read the US Constitution literally on this point about the right to “keep and bear” a single shot musket using black powder and lead ball. The whole point of the “strict constructionist” approach – the approach of the distinguished, now late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who passed away on Feb 13, 2016 – is to understand what the original framers of the Constitution had in mind at the time the document was drawn up and be true to that intention in so far as one can put oneself in their place. While this can be constraining, it can also be liberating.

Consider: No one in 1787 – or even 1950 – could have imagined that the fire power of an entire regiment would be placed in the hands of single individual with a single long gun able to deliver dozens of shots a minute with rapid reload ammo clips. (I will not debate semi-automatic versus automatic – the mass killer in LasVegas had an easy modification to turn a semi-automatic into an automatic.)

Unimaginable. Not even on the table.

This puts the “right” to “bear arms” in an entirely new context. You have got a right to a single shot musket, powder and ball. You have got a right to a single shot every two minutes, not ten rounds a second for minutes on end, or until the SWAT team arrives. The Founding Fathers did not intend the would-be killer being perversely self-expressed on social media to “out gun” school security staff who are equipped with a six shooter. Now the damage done by such a weapon as the Brown Bess should not be under-estimated. Yet the ability to cause mass casualties is strictly limited by the relatively slow process of reloading.

The Founding Fathers were in favor of self-defense, not in favor of causing mass casualties to make a point in the media. The intention of the Second Amendment is to be secure as one builds a farm in the western wilderness, not wipe out a 4th grade class. I think you can see where this is going.

Let us try a thought experiment. You know, how in Physics 101, you imagine taking a ride on a beam of light? I propose a thought experiment based on historical empathy: Issue every qualified citizen a brown bess musket, powder, and ball. What next?

Exactly what we are doing now! Okay, bang away guys. This is not funny – and yet, in a way, it is. A prospective SNL cold open? When the smoke clears, there is indeed damage, but it is orders of magnitude less than a single military style assault rifle weapon. When the smoke clears, all-too-often weapons are found to be in the hands of people who should not be allowed to touch them – the mentally unstable, those entangled in the criminal justice system, and those lacking in the training needed to use firearms safely.

More to the point, this argument needs to be better known in state legislatures, Congress, and the Supreme Court. All of a sudden the strict constructionists are sounding more “loose” and the “loose” constructionist, more strict. It would be a conversation worth having.

The larger question is what is the relationship between arbitrary advances in technology and the US Constitution. The short answer? Technology is supposed to be value neutral – one can use a hammer to build a house and take shelter from the elements or to bludgeon your innocent neighbor. However, technology also famously has unanticipated consequences. In the 1950s, nuclear power seemed like a good idea – “free” energy from splitting the atom. But then what to do with the radioactive waste whose half life makes the landscape uninhabitable by humans for 10,000 years? Hmmm – hadn’t thought about that. What to do about human error – Three Mile Island? And what to do about human stupidity – Chernobyl? What to do about unanticipated consequences? Mass casualty weapons in the hands of people intent on doing harm? But wait: guns do not kill people; people with guns kill people. Okay, fine.

There are many points to debate. For example, guns are a public health issue: getting shot is bad for a person’s health and well-being. Some citizens have a right to own guns; but all citizens have a right not to get shot. People who may hurt themselves or other people should be prevented from getting access to firearms. There are many public health – and mental health – implications, which will not be resolved here. There are a lot of gun murders in Chicago – including some using guns easily obtained in Texas and related geographies. The point is not to point fingers, though that may be inevitable. The guidance is: Do not ask what is wrong – rather ask what is missing, the availability of which would make a positive different. In this case, one important thing that is missing is historical empathy.

Because the consequences of human actions – including technological innovation – often escape from us, it is necessary to consider processes for managing the technology, providing oversight – in short, regulation. Regulation based on historical empathy. Gun regulation . Do it now.

That said, I am not serious about distributing a musket and powder and ball to every qualified citizen in place of (semi) automatic weapons – this is an argument called a “reduction to absurdity”; but I’ll bet the Founding Fathers would see merit in the approach. There’s a lot more to be said about this – and about historical empathy – but in the meantime, I see a varmint coming round the bend – pass me my brown bess!

Additional Reading

Thomas Kohut. (2020). Empathy and the Historical Understanding of the Human Past. London: Routledge.

PS Please send a copy of this editorial to your US Congressional representatives in the House and Sensate.

A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy (the book)

You don’t need a philosopher to tell you what empathy is; you need a philosopher to help you distinguish the hype and the over-intellectualization from a rigorous and critical empathy.

Every parent, teacher, health care worker, business person with customers, and professional with clients, knows what empathy is: Be open to the other person’s feelings,

Cover Art: A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy

take a walk in their shoes, give them back their own experience in one’s own words such that they recognize it as theirs.

It is important to note that one may usefully take off your own shoes before trying on those of the other individual. This is perhaps implied in the folk definition of empathy, but overlooked in the over-intellectualization that occurs in academic treatments of the subject.

Okay – I’ve read enough – I want to order the book (compelling priced at $10 (US)): Order A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy

So why is empathy in such short supply? Because we are mistaking the breakdowns of empathy – emotional contagion, conformity, projection, gossip, and getting lost in translation – for authentic empathy with one another in community. Drive out cynicism, shame, resignation, bullying, and empathy naturally shows up. There is enough empathy to go around. Get some here.

In this volume, Lou Agosta engages thirty three key articles from the great contributors to empathy studies such as William Ickes, Shaun Gallagher, and Dan Zahavi. Agosta distinguishes the hype from the substance, the wheat from the chafe, and the breakdowns of empathy from a rigorous and critical empathy itself as the foundation of community.

After debunking the prevailing scientism of empathy, this volume lays out a rigorous and critical empathy, leading the way forward with empathy studies that actually enable us to relate to one another.

rigorous and critical empathy itself as the foundation of community.

After debunking the prevailing scientism of empathy, this volume lays out a rigorous and critical empathy, leading the way forward with empathy studies that actually enable us to relate to one another.

Meanwhile, even more praise from the critics for A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy by Lou Agosta

“Agosta’s book is at the right place and the right time. One of the most exciting things about emerging areas of academic study is when a dialogue can be enjoined among those with various insights. It is in this way that an understanding of the core subject matter (in this case empathy) can grow and be enriched. Lou Agosta’s latest book does just this. It begins with an artifact […] The Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Empathy (2017) and it engages with the various contributors individually and with some of the major themes in a multi-disciplinary way—such as social psychology and the phenomenology of empathy, and situates them into how empathy might be practiced. (Thus, it continues the practice-oriented methodology of Agosta’s Empathy Lessons that has been influential.)

“What makes A Review so successful is that we are presented with one mind (Agosta’s) in dialogue with many minds. This does two things: (a) it pulls together [the Handbook’s] vision; and (b) it extends the dialogue inviting other essays to be written to further enrich the dialogue. Both of these objectives creates space for the debate and discussion of empathy which has established itself as an important component of several disciplines, e.g., ethics, social/political philosophy, sociology, literary theory, and psychology. I predict that this influence will continue to grow. It is a great read for scholars and a crucial acquisition for university libraries.” Michael Boylan, professor of philosophy at Marymount University and author of Fictive Narrative Philosophy: How Literature can act as Philosophy,and the philosophical novel T-Rx: The History of a Radical Leader.

“In this, his fifth book, Lou Agosta cements his status as the preeminent expert on empathy. I, a psychologist and psychoanalyst, know of the view of empathy in my fields. Agosta here deftly acquainted me with the way empathy is seen by other disciplines, such as philosophy, cognitive science, neuroscience, anthropology, and aesthetics. With his lively mind and fluent, playful writing style, he enlightens and entertains the reader.” James W. Anderson, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Northwestern University, and President, Chicago Psychoanalytic Society (2017-2019)

“Lou Agosta calls it as he sees it. His distinct voice is both knowledgeable and radical in his advocacy of a conscious and deliberate embrace of empathy. He is passionate in putting forward that the understanding of empathy and its daily application is the essential element in improving the human condition in modern times.

“Lou Agosta’s most recent book in his series on empathy reviews the philosophical origins of empathy and current controversies. His tour de force reviews thirty three authors on empathy and makes a critical evaluation of both important contributions and limitations of the extensive literature regarding key concepts in the field of empathy studies. The book will appeal to those who believe empathy is critical in all aspects of interpersonal relatedness from psychotherapy to organizational culture.

“Topics covered include the core importance of empathy in human being. Empathy is reviewed from an historical perspective including philosophical, moral, aesthetic, cultural and clinical frames of exploration.

“Lou Agosta is a natural teacher and rare will be the reader who does not learn something significant from his new book.” Dennis Beedle, MD, former Chair, Department of Psychiatry, Saint Anthony Hospital, Chicago

Click here to order: Order A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy

Short BIO: Lou Agosta, PhD, teaches and practices empathy at Ross University Medical School at Saint Anthony Hospital, Chicago, Il. He is the author of three peer-reviewed books in the series A Rumor of Empathyand the best selling, popular book, Empathy Lessons. His PhD is from the philosophy department of the University of Chicago and is entitled Empathy and Interpretation. He is an empathy consultant in private practice in Chicago, delivering empathy lessons, therapy, and life coaching, to individuals and organizations.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Review: Empathy, Embodiment, and the Person by James Jardine

The occasion for James Jardine’s engaging and complex book is the publication of the critical edition of Husserl’s drafts for Ideas II, edited (separately) by Edith Stein and Ludwig Landgrabe as Husserliana IV/V [Hua]. Jardine notes:

“I draw upon a forthcoming volume of Husserliana which, for the first time, presents the original manuscripts written by Husserl for the project of Ideen II (Hua IV/V), a now-finished editorial task which was carefully pursued for several years by Dirk Fonfara at the Husserl-Archiv in Köln” [Jardine 2022: 4].

For this substantial scholarly contribution, we, the academic reading public, are most deeply grateful. We are also grateful for James Jardine’s penetrating and dynamic engagement with the cluster of issues around empathy, ego, embodiment and community raised in Husserl’s Ideas II. This is also the place to note that like many academic books, the pricing is such that individuals will want to request that their college, university, or community library order the book rather than buy it retail.

Empathy is a rigorous and critical practice. The commitment is always to be charitable in reviewing another’s work, and this is especially so when the topic is empathy. An empathic review of a work on empathy requires – sustained and expanded empathy. Any yet is not a softball review and Jardine’s work presents challenges from logical, phenomenological and rational reconstruction perspectives. It is best to start by letting Jardine speak for himself and at some length:

“I motivate and explore in detail the claim that animate empathy involves the broadly perceptual givenness of another embodied subject as experientially engaged in a common perceptual world. Interpersonal empathy, which I regard as founded upon animate empathy, refers by contrast to the fully concrete variety of empathy at play when we advert to another human person within a concrete lifeworldly encounter” [Jardine: 5].

“ […] [O]nce we recognise that the constitution of a common perceptual world is already enabled by animate empathy—without an analysis of the latter being exhausted by our pointing out this function—this allows us to render thematic the specific forms of foreign subjectivity and interpersonal reality that are opened up by interpersonal empathy, which involves but goes far beyond animate empathy” [Jardine: 88].

The key distinction is clear: “animate empathy” is distinct from “interpersonal empathy.” This distinction is widely employed in empathy scholarship, even if not in these exact terms, with many varying nuances and shades of meaning. This distinction roughly corresponds to the distinctions between affective and cognitive empathy, between empathic receptivity and empathic understanding, and, most generically, between “top down” and “bottom up” empathy. Arguably, the distinction even corresponds to that between the neurological interpretation of empathy using mirror neurons (or a mirroring system just in case mirror neurons do not exist) and the folk definition of empathy as “taking a walk in the other person’s shoes (with the other’s personality)”.

I consider it an unconditionally positive feature of Jardine’s work that he does NOT mention mirror neurons, which are thoroughly covered elsewhere in the literature (e.g., V. Gallese, 2006, “Mirror Neurons and Intentional Attunement,” JAPA).

From a phenomenological point of view, Jardine succeeds in showing that Husserl is a philosopher of empathy – animate empathy. Even if Maurice Merleau-Ponty does carry the work of phenomenology further into neurology and psychology, having inherited Jean Piaget’s chair, Husserl is already the phenomenologist of the lived experience of the body. The human (and mammalian!) body that one encounters after every phenomenological bracketing and epoché is a source of animate expressions of life. A pathological act of over-intellectualization is required not to see the body as expressing life in the form of sensations, feelings, emotions, affects, and thoughts. There are dozens and dozens of pages and lengthy quotations devoted to this idea. Here are a couple of quotes by Husserl that make the point:

“We ‘see’ the other and not merely the living body of the other; the other itself is present for us, not only in body, but in mind: ‘in person’” (Hua IV/V 513/Hua IV 375, transl. modified [1917]).

“The unity of the human being permits parts to be distinguished, and these parts are animated or ensouled (beseelt) unities (Hua IV/V 582 [1916/1917])” [Jardine 2022: 78].

Animate empathy LIVES in Husserl’s Ideas II. In addition, the shared space of living physical bodies creates a clearing for the intersubjective perception of natural (physical) objects in the common world of things and events. In that sense, empathy is at the foundation of the shared intersubjective world of thing-objects (as Heidegger would say “present to hand”).

However, the big question – for Husserl, Jardine, and all of us who follow – is does Husserl’s version of empathy found the intersubjective world of conscious human beings with intentional perceptions, emotions, actions, and personal engagements?

After nearly three hundred pages of engaging, useful, and lengthy quotations from Landgreb’s and Stein’s drafts of Ideas II, closely related texts of Husserl, and Jardine’s penetrating and incisive commentary, this reviewer was still not sure. In addition to my own shorting-comings, there are significant other reasons and considerations.

Jardine’s work is an innovative train-wreck, rather like Leonardo’s fresco the “Last Supper” – even at the start, da Vinci’s masterpiece was a magnificent wreck as the underlying plaster of the fresco did not “set up” properly. In this case, the underlying plaster is Husserl’s “work in progress” of Ideas II. (I acknowledge “work in progress” is my description, not Jardine’s.)

As is well known, Husserl himself withheld the manuscript of Ideas II from publication. He was not satisfied with the results, having been accused of succumbing to the problematic philosophical dead-end of solipsism, the inability to escape from the isolated self, knowing only itself. Will empathy solve the problem?

It is a further issue (not mentioned by Jardine) that everything without exception that Husserl actually published in his life about empathy after he published Ideas I (1913), makes “empathy [Einfühlung]” nonfoundational in relation to the givenness of the other individual, displacing it “upstairs.” For example, Husserl writes in the Cartesian Meditations:

“The theory of experiencing someone else, the theory of so-called ‘empathy [Einfühlung],’ belongs in the first story above our ‘transcendental aesthetics’” [Husserl 1929/31: 146 (173); see also Agosta, 2010: 121].

Now strictly speaking, Jardine could reply that quoting Husserl’s Cartesian Meditations is out of scope for an engagement with Ideas II, and that is accurate enough as it stands; but what is not out of scope is the challenge of solipsism with which Husserl was wrestling philosophically throughout his career. As noted, at the level of the Cartesian Meditations (which Jardine does occasionally quote when it suits his purpose (but not the above-cited quote!)), empathy belongs to the first story upstairs above his “transcendental aesthetics,” as Husserl writes, quoting a Kantian distinction.

Thus, we engage with Jardine’s implicit reconstruction of Husserl’s repeated attempts to navigate the labyrinth of phenomenological experience, joining and separating the subject/self and other individual.

Jardine follows Husserl from the solipsistic frying pan into the fire by quoting Husserl accurately as saying the self and other are separated by an abyss:

“Husserl calls out a “series of appearances (…) are exchanged, while each subject yet remains ineluctably distinct from every other by means of an abyss, and no one can acquire identically the same appearances as those of another. Each has his stream of consciousness displaying a regularity (Regelung) that encompasses precisely all streams of consciousness, or rather, all animal subjects (die eben über alle Bewusstseinsströme bzw. Animalischen Subjekte übergreift)” (Hua IV/V 254–255/Hua IV 309, transl. modified [1913])” [Jardine: 134 (emphasis added)].

Husserl tries a reduction to absurdity to escape from the solipsistic world of this abyss between self and other, supposing the world really were mere semblances. One will eventually encounter a person who is a non-semblance. This other individual who transforms the mere semblance into actually appearance awakens one from the dream of solipsism If it could be shown or argued that this other individual is necessarily given/presented/encountered, then all one’s previous solipsistic experience would be like hallucinatory madness. With apologies to Hilary Putnam, this is Husserl’s “brain in a vat” moment [Jardine: 126]:

“…[A]ny intersubjective “apperceptive domain”, Husserl claims, it is conceivable that, in the solipsistic world, “I have the same manifolds of sensation and the same schematic manifolds,” and, in as much as functional relations hold between such manifolds, then it may be that “the ‘same’ real things, with the same features, appear to me and, if everything is in harmony, exhibit themselves as ‘actually being’” (Hua IV/V 295 [1915]; cf. Hua IV 80). And yet, if other human living bodies were to then “show up” and be “understood” as such, the feigned reality of our experienced ‘things’ would be called into question:

Now all of a sudden and for the first time human beings are there for me, with whom I can come to an understanding [. . . .] As I communicate to my companions my earlier lived-experiences an d they become aware of how much these conflict with their world, constituted intersubjectively and continuously exhibited by means of a harmonious exchange of experience, then I become for them an interesting pathological object, and they call my actuality, so beautifully manifest to me, the hallucination of someone who up to this point in time has been mentally ill (Hua IV/V 295–296/Hua IV 79–80, transl. modified [1915])” [Jardine: 126].

This is a remarkable passage from Husserl, and we are indebted to Jardine’s scholarship for calling it to our attention. The thing that is missing or must be rationally reconstructed in Husserl is the necessity of the givenness of the other; but then, of course, the hermeneutic circle closes and the problem of solipsism is undercut, does not arise, and the character of phenomenology shifts. As is often the case, the really interesting work gets done in a footnote:

“For Husserl, this insight, that a phenomenological treatment of the constitutive relation between subject and world would have to address the (co-)constitutive role played by intersubjectivity, raises issues which cannot be addressed by a single analysis, but which rather demand a rethinking of the entire project of phenomenology” [Jardine: 127 (footnote) (reviewer’s embolding)].

There is nothing wrong with Jardine’s argument, yet, as noted, since this is not a softball review, there is something missing. The distinction “reconstruction” or “rational reconstruction” may usefully be applied to Husserl’s description and/or analysis of empathy. Jardine attempts to cross the abyss by means of interpersonal empathy. To that purpose, Jardine marshals the resources of narrative and of Alex Honneth’s distinction of “elementary recognition.”

To his credit, Jardine holds open the possibility that Husserl’s use of “empathy” does provide the foundation, at the time of Ideas II (1915 – 1917 and intermittently in the 1920s as Stein and Landgrabe try to “fix” the manuscript). Yet Jardine pivots to Alex Honneth’s (1995) key distinction of recognition (“elementary recognition,” to be exact) to provide the missing piece that Husserl struggled to attain. I hasten to add that I think this works well enough, especially within the context of an implied rational reconstruction of empathy within Husserlian/Honnethian dynamics and Husserl’s verstickung in solipsism.

However, this move also shows that Husserl did not quite “get it” as regards empathy being the foundation of interpersonal relations or community. As noted, Husserl is quite explicit in his published remarks that empathy gets “kicked upstairs” and is not a part of the foundation but of the first story above immediate experience, which as those in Europe know well is really the second story in the USA.

As noted, Jardine makes the case for bringing in supplementary secondary, modern thinkers to complement the “work in progress” status of Ideas II as a “messy masterpiece” (Jardine’s description, p. 4). I hasten to add that I do not consider Edith Stein a secondary thinker as her own thinking is primarily and complexly intertwined with that of Husserl. Likewise, Dan Zahavi is an important thinking in Jardine’s subtext and background, whose (Zahavi’s) contributions on empathy and Husserlian intersubjectivity (Husserliana XIV – XV) align with my own (2010) and are not an explicit part of the surface structure of the Jardine’s text.

Relying on the good work that Jardine initiatives, the reconstruction of Husserl’s relationship to empathy can be done in three phases. Husserl first attempts straightaway to connect the subject/self and the other individual person using empathy in Ideas I (1913). This results in the accusation of solipsism. The accusation “has legs,” because arguably Husserl fails to clarify that the other is an essential part of the intentional structure of empathy, even if the noematic object is inadequate or unsatisfied in a given context. Husserl then tries different methods of crossing the “abyss,” including Ideas II and the animate empathic expressions of the lived body. Husserl himself is not happy with the result as it does not quite get to what Jardine properly calls “interpersonal empathy.” At the risk of over-simplification, “interpersonal empathy” what happens we when “get understood” by another person in the context of human emotions and motivations.

The engagement with the critical edition of the second and third volumes of Ideas, provides extensive evidence that for Husserl, the world of experience is dense with empathy. But at the level of Ideas II (and HuaIV/V), there is an ambivalence in Husserl whether he wants to make empathy a part of the superstructure or infrastructure of the shared, common intersubjective world (especially non-animate things in that world). This can be tricky because, as Jardine makes clear, animate empathy is enough to give us intersubjective access to a world of physical objects and things. However, that is still not intersubjectivity in the full sense of relating to other selves who are spontaneous separate centers of conscious emotional and intentional acts.

I have suggested, separately (Agosta 2010, 2014) that Husserl steps back in his published works from embracing the intentional structure of empathy (in all its aspects) as full out foundation of intersubjectivity. However, in the Nachlass, especially Hua XIV and XV, empathy is migrating – evolving – moving – from the periphery to the foundation of intersubjectivity in the full sense of a community of intentional subjects.

Meanwhile, Husserl attempts to constitute intersubjectivity along with empathy (the latter as not foundational) by reduction to a “sphere of ownness” in the Cartesian Meditations (1928/32). The debate continues and Husserl later elaborates the distinction lifeworld (Lebenswelt), arguably under the influence of Heidegger, Scheler, and others, which lifeworld, however, is applied to nature not social human community. Husserl’s Nachlass, especially volumes Hua XIV and Hua XV demonstrate in detail that Husserl was moving in a hermeneutic circle and empathy was evolving from the periphery to the foundation of intersubjectivity (Zahavi 2006; Agosta 2010, 2014).

In lengthy quotations for the Cartesian Meditations and Phenomenological Psychology, Jardine validates that Husserl engages with personal character in the sense of personality. Jardine is on thin ice here, for though Husserl calls out “autobiography” and “biography” – and what are these except “self writing” and “life writing,” yet that is a lot to justify that Husserl goes more than two words in the direction of narrative.

Of course, one can build a case for a rational reconstruction of Husserl’s subtext as a hermeneutic phenomenology of narrative or the other as oneself and vice versa. And it results in the work of – Paul Ricoeur! That Husserl is not Paul Ricoeur – or Levinas or Heidegger or Merleau-Ponty or Sartre or Hannah Arendt, or, for that matter, Donald Davidson – takes nothing away from the innovations contributed by Husserl. It is rather a function of Jardine’s noodling with the interesting connections between all these. Nothing wrong with that as such – yet there is something missing – Husserl!

Therefore, the guidance to the Jardine is to let Husserl be Husserl. The author really seems to be unable to do that. There is nothing wrong with what Jardine is doing – from sentence to sentence, the argument proceeds well enough. But the reader finds himself in a discussion of “narrative” in the same sentence as Husserl and Ideas II. I hasten to add that I appreciate narrative as a research agenda, and have seven courses by Paul Ricoeur on my college and graduate school transcripts. And yet, once again, there is something missing – one can read Husserl against himself and maybe Jardine thinks that is what he is doing – but it is rather like what The Salon said about the paintings of Cezanne – he paints with a pistol – paint is splattered all over the place – the approach is innovative – but we were expecting impressionism and get – Jackson Pollack! We were expecting phenomenology and got – Donald Davidson or P.F. Strawson or Honneth – all penetrating thinkers, everyone, without exception.

In reading Jardine, I imagined that the transition from animate to interpersonal empathy could be facilitated – without leaving the context of Husserl’s thinking – by the many passages in which Husserl describes the subject’s body as being the zero point and the other’s as being another zero point.

Allowing for an intentional act of reversing position with the other, does this not provide an ascent routine to the folk definition of [interpersonal] empathy of “taking a walk in the other’s person’s shoes” [or, what is the same thing, the other person’s zero point]? Unless I have overlooked something, I do not find this argument in Jardine, though it might have been made the basis of a rational reconstruction of interpersonal empathy sui generis in Husserl without appeal to other thinkers. Thus, Jardine describes the “here/there” dynamic in Husserl:

“Accordingly, we can say that for a subject to empathetically grasp another’s living body she must comprehend it as a foreign bodily “here” related to a foreign sphere of sense-things (to which foreign “theres” correspond), where these are recognised as transcending – but also, at least in the case of “normality,” as harmonious with – my own bodily “here” and the sense-things surrounding it [. . . . ] Husserl suggests that, when the materiality of the other’s body ‘over there’ coincides, in its “general type,” with my own lived body ‘here’ in its familiar self-presence, “then it is “seen” as a lived body, and the potential appearances, which I would have if I were transposed to the ‘there,’ are attributed to as currently actual; that is, an ego is acknowledged in empathy (einverstanden wird) as the subject of the living body, along with those appearances and the rest of the things that pertain to the ego, its lived experiences, acts, etc.” That is, alongside the perceptible similarity of my lived body and the other’s [. . . ], this empathetic apprehension of a foreign sphere of sense-things also rests upon a further structural feature of perceived space; namely, that each ‘there’ is necessarily recognised as a possible ‘here,’ a possibility whose actualisation would rest solely upon my freely executing the relevant course of movement’” [Jardine: 131].

Jardine performs engaging inferential and speculative gyrations to save Husserl from so much as a hint of the accusation of inconsistency instead of emphasizing that Husserl’s use and appreciation of empathy develops, evolves, is elaborated. Husserl gets more intellectual distance from and closeness to empathy as he learns of Max Scheler’s work on the forms of sympathy and Heidegger’s work on Mitsein (which, I hasten to add, are in Jardine’s extensive and excellent footnotes and references).

Another approach to crossing the abyss between self and other is a transcendental argument. This goes beyond anything Jardine writes, but if offered in the Husserlian spirit and if it helps to put his project in the broader context, then it warrants consideration.

The argument informally: The distinction between self and other is not a breakdown of empathy; the distinction is the transcendental requirement, the presupposition, for empathy. If I lose the distinction between self and other, then I get emotional contagion, conformity, projection (Lipps), or communications that get lost in translation. Only if the distinction between self and other stand firm, is it possible, invoking aspects of acts of empathic intentionality, to communicate feelings (sensation, emotion) across the boundary between self and other; relate to the other individual as the possibility of reciprocal humanity; take a walk in the other’s shoes with aspects of their personality; and respond empathically to the other with performative linguistic acts of recognition. We do not merely express recognition; we perform it, thereby, instituting mutual dignity.

Husserl’s blind spot in this area and – do I dare say it? – perhaps Jardine’s as well is a function of remaining at the level of a single subject phenomenology, at least until the elaboration of the distinction, life-world (Lebenswelt). Until we explicitly get to the lifeworld, what would a multisubject phenomenology look like? The short answer is Heidegger’s Mitsein, Levinas on the fact and face of The Other, Ricoeur on oneself as other, or Sartre on the gaze of the other bestowing individuality and identity on the one.

Along these lines, Jardine usefully identifies the text where Husserl credits the other with constituting the social self of the self. The other gives me my humanity and without the other’s constitutive activity, one does not get to be a human being. Here Husserl comes closest to acknowledging that the one individual gets her/his humanity from the other individual. This is Jardine directly quoting Husserl: