Juneteenth: Beloved in the Context of Radical Empathy

For those who may require background on this new federal holiday, June 19th – Juneteenth – it was the date in 1865 that US Major General Gordon Granger proclaimed freedom for enslaved people in Texas some two and a half years after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Later, the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution definitively established this enshrining of freedom as the law of the land and, in addition, the 14th Amendment extended human rights to all people, especially formerly enslaved ones. This blog post is not so much a book review of Beloved as a further inquiry into the themes of survival, transformation, liberty, trauma – and empathy. (By is a slightly updated version of an article that was published on June 27, 2023.)

“Beloved” is the name of a person. Toni Morrison builds on the true story of Margaret Garner, an enslaved person, who escaped with her two children even while pregnant with a third, succeeding in reaching freedom across the Ohio River in 1854. However, shortly thereafter, slave catchers (“bounty hunters”) arrived with the local sheriff under the so-called fugitive slave act to return Margaret and her children to slavery. Rather than submit to re-enslavement, Margaret tried to kill the children, also planning then to kill herself. She succeeded in killing one, before being overpowered. The historical Margaret received support from the abolitionist movement, even becoming a cause celebre. The historical Margaret is named Sethe in the novel. The story grabs the reader by the throat – at first relatively gently but with steadily increasing compression – and then rips the reader’s guts out. The story is complex, powerful, and not for the faint of heart.

The risks to the reader’s emotional equilibrium of engaging with such a text should not be underestimated. G. H. Hartman is not intentionally describing the challenge encountered by the reader of Beloved in his widely-noted “Traumatic Knowledge and Literary Studies,” but he might have been:

“The more we try to animate books, the more they reveal their resemblance to the dead who are made to address us in epitaphs or whom we address in thought or dream. Every time we read we are in danger of waking the dead, whose return can be ghoulish as well as comforting. It is, in any case, always the reader who is alive and the book that is dead, and must be resurrected by the reader” (Hartman 1995: 548).

Waking the dead indeed! Though technically Morrison’s work has a gothic aspect – it is a ghost story – yet it is neither ghoulish nor sensational, and treats supernatural events rather the way Gabriel Garcia Marquez does – as a magical or miraculous realism. Credible deniability or redescription of the returned ghost as a slave who escaped from years-long sexual incarceration is maintained for a hundred pages (though ultimately just allowed to fade away). Morrison takes Margaret/Sethe’s narrative in a different direction than the historical facts, though the infanticide remains a central issue along with how to recover the self after searing trauma and supernatural events beyond trauma. The murdered infant had the single word “Beloved” chiseled on her tombstone, and even then the mother had to compensate the stone mason with non-consensual sex. An explanation will be both too much and too little; but the minimal empathic response is to try to say something that will advance the conversation in the direction of closure, the integration of unclaimed experience (to use Cathy Carruth’s incisive phrase), and recovery from trauma. Let us take a step back.

Morrison is a master of conversational implicature. What is that? “Conversational implicature” is an indirect speech act that suggests an idea or thought, even though the thought is not literally expressed. Conversational implicature lets the empathy in – and out – to be expressed. Such implicature expands the power and provocation of communication precisely by not saying something explicitly but hinting at what happened. The information is incomplete and the reader is challenged to feel her/his way forward using the available micro-expressions, clues, and hints. Instead of saying “she was raped and the house was haunted by a ghost,” one must gather the implications. One reads: “Not only did she have to live out her years in a house palsied by the baby’s fury at having its throat cut, but those ten minutes she spent pressed up against dawn-colored stone studded with star chips, her knees wide open as the grave, were longer than life, more alive, more pulsating than the baby blood that soaked her fingers like oil” (Morrison 1987: 5–6). Note the advice above about “not for the faint of heart.”

The reader does a double-take. What just happened? Then a causal conversation resumes in the story about getting a different house as the reader tries to integrate what just happened into a semi-coherent narrative. Yet why should a narrative of incomprehensibly inhumane events make more sense than the events themselves? No good reason – except that humans inevitably try to make sense of the incomprehensible.“Not a house in the country ain’t packed to its rafters with some dead Negro’s grief” (1987: 6). One of the effects is to get the reader to think about the network of implications in which are expressed the puzzles and provocations of what really matters at a fundamental level. (For more on conversational implicature see Levinson 1983: 9 –165.)

In a bold statement of the obvious, this reviewer agrees with the Nobel Committee, who awarded Morrison the Novel Prize in 1988 for this work. This review accepts the high literary qualities of the work and proposes to look at three things. These include: (1) how the traumatic violence, pain, suffering, inhumanity, drama, heroics, and compassion of the of the events depicted (consider this all one set), interact with trauma and are transformed into moral trauma; (2) how the text itself exemplifies empathy between the characters, bringing empathy forth and making it present for the reader’s apprehension; (3) the encounter of the reader with the trauma of the text transform and/or limit the practice of empathizing itself from standard empathy to radical empathy.

So far as I know, no one has brought Morrison’s work into connection with the action of the Jewish Zealots at Masada (73 CE). The latter, it may be recalled, committed what was in effect mass suicide rather than be sold into slavery after being militarily defeated and about-to-be-taken-prisoner by the Roman army. The 960 Zealots drew lots to kill one another and their wives and children, since suicide technically was against the Jewish religion.

On further background, after the fall of Jerusalem as the Emperor Titus put down the Jewish rebellion against Rome in 73 CE, a group of Jewish Zealots escaped to a nearly impregnable fortress at Masada on the top of a steep mountain. (Note Masada was a television miniseries starring Peter O’Toole (Sagal 1981).) Nevertheless, Roman engineers built a ramp and siege tower and eventually succeeding in breaching the walls. The next day the Roman soldiers entered the citadel and found the defenders and their wives and children all dead at their own hands. Josephus, the Jewish historian, reported that he received a detailed account of the siege from two Jewish women who survived by hiding in the vast drain/cistern – in effect, tunnels – that served as the fortress’ source of water.

The example of the Jewish resistance at Masada provides a template for those facing enslavement, but it does not solve the dilemma that killing one’s family and then committing suicide is a leap into the abyss at the bottom of which may lie oblivion or the molten center of the earth’s core, a version of Dante’s Inferno. So all the necessary disclaimers apply. This reviewer does not claim to second guess the tough, indeed impossible, decisions that those in extreme situations have to make. One is up against all the debates and the arguments about suicide.

Here is the casuistical consideration – when life is reduced from being a human being to being a slave who is treated as a beast of burden and whose orifices are routinely penetrated for the homo- and heteroerotic pleasure of the master, then one is faced with tough choices. No one is saying what the Zealots did was right – and two wrongs do not make a right – but it is also not obvious that what they did was wrong in the way killing an innocent person is wrong, who might otherwise have a life going about their business gardening, baking bread, or fishing. This is the rock and the hard place, the devil and deep blue sea, the frying pan or the fire, the Trolley Car dilemma (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem). This is Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the Desert Fox, who after the unsuccessful attempt in June 1944 to assassinate Hitler (of which Rommel apparently had knowledge but took no action), was allowed by the Nazi authorities to take the cyanide pill. This is Colonel George Armstrong Custer with one bullet left surrounded by angry Dakota warriors who would like to slow cook him over hot coals. Nor as far as I know is the bloody case of Margaret Garner ever in the vast body of criticism brought into connection with the suicides of Cicero and Seneca (and other Roman Stoics) in the face of mad perpetrations of the psychopathic Emperor Nero. This is a decision that no one should have to make; a decision that no one can make; and yet a decision that the individual in the dilemma has to make, for doing nothing is also a decision. In short, this is moral trauma.

A short Ted Talk on trauma theory is appropriate. Beloved is so dense with trauma that a sharp critical knife is needed to cut through it. In addition to standard trauma and complex trauma, Beloved points to a special kind of trauma, namely, moral trauma or as it sometimes also called moral injury, that has not been much recognized (though it is receiving increasing attention in the context of war veterans (e.g. Shay 2014)). “Moral trauma (injury)” is not in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), any edition, of the American Psychiatric Association, nor is it even clear that it belongs there, since the DSM is not a moral treatise. Without pretending to do justice to the vast details and research, “trauma” is variously conceived as an event that threatens the person’s life and limb, making the individual feel he or she is going to die or be gravely injured (which would include rape). The blue roadside signs here in the USA that guide the ambulance to the “Trauma Center” (emergency department that has staff on call at all times), suggest an urgent emergency, in this case usually but not always, a physical injury.

Cathy Caruth (1996) concisely defines trauma in terms of an experience that is registered but not experienced, a truth or reality that is not available to the survivor as a standard experience, “unclaimed experience.”The person (for example) was factually, objectively present when the head on collision occurred, but, even if the person has memories, and would acknowledge the event, paradoxically, the person does not experience it as something the person experienced. The survivor experiences dissociated, repetitive nightmares, flashbacks, and depersonalization. At the risk of oversimplification, Caruth’s work aligns with that of Bessel van der Kolk (2014). Van der Kolk emphasizes an account that redescribes in neuro-cognitive terms a traumatic event that gets registered in the body – burned into the neurons, so to speak, but remains sequestered – split off or quarantined – from the person’s everyday going on being and ordinary sense of self. For both Caruth and van der Kolk, the survivor is suffering from an unintegrated experience of self-annihilating magnitude for which the treatment – whether working through, witnessing, or (note well) artistic expression – consists in reintegrating that which was split off because it was simply too much to bear.

For Dominick LaCapra (1999), the historian, “trauma” means the Holocaust or Apartheid (add: enslavement to the list). LaCapra engages with how to express in writing such confronting events that the words of historical writing and literature become inadequate. The words breakdown, fail, seem fake no matter how authentic. And yet the necessity of engaging with the events, inadequately described as “traumatic,” is compelling and unavoidable. Thus, LaCapra (1999: 700) notes: “Something of the past always remains, if only as a haunting presence or revenant.” Without intending to do so, this describes Beloved, where the infant of the infanticide is literally reincarnated, reborn, in the person named “Beloved.” For LaCapra, working through such traumatic events is necessary for the survivors (and the entire community) in order to get their power back over their lives and open up the possibility of a future of flourishing. This “working through” is key for it excludes denial, repression, suppression, and, in contrast, advocates for positive inquiry into the possibility of transformation in the service of life. Yet the attempt at working through of the experiences, memories, nightmares, and consequences of such traumatic events often result in repetition, acting out, and “empathic unsettlement.” Key term: empathic unsettlement. From a place of safety and security, the survivor has to do precisely that which she or he is least inclined to do – engage with the trauma, talk about it, try to integrate and overcome it. Such unsettlement is also a challenge and an obstacle for the witness, therapist, or friend providing a gracious and generous listening.

LaCapra points to a challenging result. The empathic unsettlement points to the possibility that the vicarious experience of the trauma on the part of the witness leaves the witness unwilling to complete the working through, lest it “betray” the survivor, invalidate the survivor’s suffering or accomplishment in surviving. “Those traumatized by extreme events as well as those empathizing with them, may resist working through because of what might almost be termed a fidelity to trauma, a feeling that one must somehow keep faith with it” (DeCapra 2001: 22). This “unsettlement” is a way that empathy may breakdown, misfire, go off the rails. It points to the need for standard empathy to become radical empathy in the face of extreme situations of trauma, granted what that all means requires further clarification.

For Ruth Leys (2000) the distinction “trauma” itself is inherently unstable oscillating between historical trauma – what really happened, which, however, is hard if not impossible to access accurately – and, paradoxically, historical and literary language bearing witness by a failure of witnessing. The trauma events are “performed” in being written up as history or made the subject of an literary artwork. But the words, however authentic, true, or artistic, often seem inadequate, even fake. The “trauma” as brought forth as a distinction in language is ultimately inadequate to the pain and suffering that the survivor has endured, which “pain and suffering” (as Kant might say) are honored with the title of “the real.” Yet the literary or historical work is a performance that may give the survivor access to their experience.

The traumatic experience is transformed – even “transfigured” – without necessarily being made intelligible or sensible by reenacting the experience in words that are historical writing or drawing a picture (visual art) or dancing or writing a poem or bringing forth a literary masterpiece such as Beloved. The representational gesture – whether a history or a true story or fiction – starts the process of working through the trauma, enabling the survivor to reintegrate the trauma into life, getting power back over it, at least to the extent that s/he can go on being and becoming. In successful instances of working through, the reintegrated trauma becomes a resource to the survivor rather than a burden or (one might dare say) a cross to bear. To stay with the metaphor, the cross becomes an ornament hanging from a light chain of silver metal on one’s neck rather than the site of one’s ongoing torture and execution. Much work and working through is required to arrive at such an outcome.

Though Beloved has generated a vast amount of critical discussion, it has been little noted that the events in Belovedrapidly put the reader in the presence of moral trauma (also called “moral injury”). Though allusion was made above to the DSM, the devil is in the details. Two levels of trauma (and the resulting post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)) are concisely distinguished (for example by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual(5th edition) of the American Psychiatric Association (2013). There is standard trauma – one survives a life changing railroad or auto accident and has nightmares and flashbacks (and a checklist of other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)). There is repeated trauma, trauma embedded in trauma, double-bind embedded in double bind. One is abused – and it happens multiple times over a course of months or years and, especially, it may happen before one has an abiding structure for cognition such as a stable acquisition of language (say to a two-year-old) or happens in such a way or such a degree that words are not available as the victim is blamed while being abused – resulting in complex trauma and the corresponding complex PTSD.

But this distinction, standard versus complex trauma (and the correlated PTSD), is inadequate in the case of moral trauma, where the person is both a survivor and a perpetrator.

Thus, an escaped slave makes it to freedom. One Margaret Garner is pursued and about to be apprehended under the Fugitive Slave Act. She tries to kill herself and her children rather than be returned to slavey. She succeeds in killing one of the girls. Now this soldier’s choice is completely different than the choice faced by Margaret/Sethe, and rather like the inverse of it, dependent on not enough information rather than a first-hand, all-too-knowledgeable acquaintance with the evils of enslavement from having survived it (so far). Yet the structural similarities are striking. Morrison says of Sethe/Margarent might also said of the soldier, “[…][S]he could do and survive things they believed she should neither do nor survive […]” (Morrison 1987: 67). Yet one significant difference between the soldier and Sethe (and the Jewish Zealots) is their answer to the question when human life ceases to be human. A casuistical clarification is in order. If human life is an unconditional good, then, when confronted with an irreversible loss of the humanness, life itself may not be an unconditional good. Life versus human life. The distinction dear to Stoic philosophy, that worse things exist than death, gets traction – worse things such as slavery, cowardice in the face of death, betraying one’s core integrity. The solder is no stoic; Sethe is. Yet both are suffering humanity.

However, one may object, even if one’s own human life may be put into play, it is a flat-out contradiction to improve the humanity of one’s children by ending their humanity. The events are so beyond making sense, yet one cannot stop oneself from trying to make sense of them. So far, we are engaged with the initial triggering event, the infanticide. No doubt a traumatic event; and arguably calling forth moral trauma. But what about trauma that is so traumatic, so pervasive, that it is the very form defining the person’s experiences. Trauma that it is not merely “unclaimed, split off” experience (as Caruth says). For example, the person who grows up in slavery – as did Sethe – has never known any other form of experience – this is just the way things are – things have always been that way – and one cannot imagine anything else (though some inevitably will and do). This is soul murder. So we have moral trauma in a context of soul murder. Soul murder is defined by Shengold (1989) as loss of the ability to love, though the individuals in Beloved retain that ability, however fragmented and imperfect it may be. Rather the proposal here is to expand the definition of soul murder to include the loss of the power spontaneously to begin something new – the loss of the possibility of possibility of the self, leaving the self without boundaries and without aliveness, vitality, an emotional and practical Zombie. In addition, as a medical professional, Shengold (1989) makes an important note: “Soul murder is a crime, not a diagnosis.” Though Morrison does not say so, and though she might or might not agree, enslavement is soul murder.

Beloved contains actual murders. Once again this is not for the fainto of heart. For example, Sethe’s friend and slave Sixo from the time of their mutual enslavement is about to be burned alive by the local vigilantes, and he gets the perpetrators to shoot him (and kill him) by singing in a loud, happy, annoying voice. He fakes “not givin’ a damn,” taking away the perpetrators’ enjoyment of his misery. It works well enough in the moment. His last. Nor is it like one murder is better (or worse) than another. However, in a pervasive context of soul murder, Sethe’s infanticide is an action taken by a person whose ability to choose -sometime called “agency” – is compromised by extreme powerlessness. Yet in that moment of decision her power is uncompromised by all the compromising circumstances and momentarily retored – whether for the better is that about which we are debating, bodly assuming the matter is debateable. One continues to try and justify and/or make sense out of what cannot have any sense. Sethe is presented with a choice (read it again – and again) that no one should have to make – that no one can make (even though the person makes the choice because doing nothing is also a choice). This is the same situation that the characters in classic Greek tragedy face, though a combination of information asymmetries, personal failings, and double-binds. Above all – double-binds. This is why tragedy was invented (which deserves further exploration, not engaged here).

Now bring empathy to moral trauma in the context of soul murder. Anyone out there in the reading audience experiencing “empathic unsettlement” (as LaCapra incisively put it)? Anyone experiencing empathic distress? If the reader is not, then that itself is concerning. “Empathic unsettlement” is made present in the reader’s experience by the powerful artistry deployed by Beloved. Yet this may be an instance in which empathy is best described, not as an on-off switch, but as a dial that one can dial up or down in the face of one’s own limitations and humanness. This is tough stuff, which deserves to be read and discussed. If one is starting to break out in a sweat, if one’s mouth is getting dry, if the pump in one’s chest is starting to accelerate its pumping, and one is thinking about putting the book down, rather than become hard-hearted, the coaching is temporarily to dial down one’s practice of empathy. While one is going to experience suffering and pain in reading about the suffering and pain of another, it will inevitably and by definition be a vicarious experience – a sample – a representation – a trace affect – not the overwhelming annihilation that would make one a survivor. Dial the empathy down in so far as a person can do that; don’t turn it off. Admittedly, this is easier said than done, but with practice, the practitioner gets expanded power over the practice of empathizing.

As noted, Morrison is a master of conversational implicature. Conversational implicature allows the empathy to get in – become present in the text and become present for the reader engaging with the text. The conversational implicature expresses and brings to presence the infanticide without describing the act itself by which the baby is killed. Less is more, though the matter is handled graphically enough. The results of the bloody deed are described – “a “woman holding a blood soaked child to her chest with one hand” (Morrison 1987: 124) – but not the bloody action of inflicting the fatal wound itself. “Writing the wound” sometimes dances artistically around expressing the wound, sometimes, not.

Returning to the story itself, Morrison describes the moment at which the authorities arrive to attempt to enforce the fugitive slave act: “When the four horsemen came – schoolteacher, one nephew, one slave catcher and a sheriff – the house on Bluestone Road was so quiet they thought they were too late” (Morrison 1987: 124). Conversational implicature meets intertextuality in the Book of Revelation of the New Testament. The four horsemen of the apocalypse herald the end of the world as we know it and the end of the world is what comes down on Sethe at this point. Perhaps not unlike the Zealots at Masada, she makes a fatal decision. Literally. As Hannah Arendt (1970) pointed out in a different political context, power and force (violence) stand in an inverse relation: when power is reduced to zero, then force – violence – comes forth. The slaves power is zero, if not a negative number. Though Sethe tries to kill all the children, she succeeds only in one instance. In the fictional account, the boys recover from their injuries and, in the case of Denver (Sethe’s daughter named after Amy Denver, the white girl who helped Sethe), Sethe’s hand is stayed at the last moment.

Beloved is a text rich in empathy. This includes exemplifications of empathy in the text, which in turn call forth empathy in the reader. The following discussion now joins the standard four aspects of standard empathy – empathic receptivity, empathic understanding, empathic interpretation, and empathic responsiveness. The challenge to the practice of empathy is that with a text and topic such as this one, does the practice of standard empathy need to be expanded, modified, or transformed from standard to radical empathy? What would that even mean? Empathy is empathy. A short definition of radical empathy is proposed: Empathy is committed to empathizing in the face of empathic distress, even if the latter is incurred, and empathy, even in breakdown, acknowledges the commitment to expanding empathy in the individual and the community.

We start with a straightforward example of empathic receptivity – affect matching. No radical empathy is required here. An example of standard empathic receptivity is provided in the text, and the dance between Denver and Beloved is performed (1987: 87 – 88):

“Beloved took Denver’s hand and place another on Denver’s shoulder. They danced then. Round and round the tiny room and it may have been dizziness, or feeling light and icy at once, that made Denver laugh so hard. A catching laugh that Beloved caught. The two of them, merry as kittens, swung to and fro, to and fro, until exhausted they sat on the floor. “

The contagious laughter is entry level empathic receptivity. Empathy degree zero, so to speak. This opening between the two leads to further intimate engagement with empathic possibility. But the possibility is blocked of further empathizing in the moment is blocked by a surprising discovery. At this point, Denver “gets it” – that Beloved is from the other side – she has died and come back – and Denver asks her, “What’s it like over there, where you were before?” But since she was killed as a baby, the answer is not very informative: “I’m small in that place. I’m like this here.” (1987: 88) Beloved, the person who returns to haunt the family, is the age she would have been had she lived.

The narrative skips in no particular order from empathic receptivity to empathic understanding. “Understanding” is used in the extended sense of understanding of possibilities for being in the world (e.g., Heidegger 1927: 188 (H148); 192 (H151)): “In the projecting of the understanding, beings [such as human beings] are disclosed in their possibility.” Empathic understanding is the understanding of possibility. What does the reader’s empathy make present as possible for the person in her or his life and circumstance? What is possible in slavery is being a beast of burden, pain, suffering, and early death – the possibility of no possibility of human flourishing. In contrast, when Paul D (a former slave who knew Sethe in enslavement) makes his way to the house of Sethe and Denver (and, unknown to him, the ghost of the baby), the possibility of family comes forth. In the story, there’s a carnival in town and Paul D, who knew Sethe before both managed to escape from the plantation (“Sweet Home”), takes her and Denver to the carnival. “Having a life” means many things. One of them is family. The possibility of family is made present in the text and the reader. That is the moment of empathic understanding of possibility:

“They were not holding hands, but their shadows were. Sethe looked to her left and all three of them were gliding over the dust hold hands. Maybe he [Paul D] was right. A life. Watching their hand-holding shadows [. . . ] because she could do and survive things they believed she should neither do nor survive [. . . .] [A]ll the time the three shadows that shot out of their feet to the left held hands. Nobody noticed but Sethe and she stopped looking after she decided that it was a good sign. A life. Could be.” (Morrison 1987: 67)

Within the story, Sethe has her own justification for her bloody deed. She is rendering her children safe and sending them on ahead to “the other side” where she will soon join them. “I took and put my babies where they’d be safe” (Morrison 1987: 193). The only problem with this argument, if there is a problem with it, is that it makes sense out of what she did. Most readers are likely to align with Paul D (a key character in the story and a “romantic” interest of Sethe’s), who at first does not know about the infanticide. Paul D learns the details of Sethe’s act from Stamp Paid, the person who is the former underground rail road coordinator, who knows just about everything that goes on, because he was a hub for the exchange of all-manner of information in helping run-away and would-be run-away slaves to survive.

Stamp feels that Paul D ought to know, though he later regrets his decision. Stamp tells Paul D about the infanticide – showing him the newspaper clipping as evidence and explaining the words that Paul D (who is illiterate) cannot read. Paul D is overwhelmed. He cannot handle it. He denies that the sketch (or photo) is Sethe, saying it does not look like her – the mouth does not match. Stamp tries to convince Paul D: “She ain’t crazy. She love those children. She was trying to out hurt the hurter” (1987: 276). Paul D asks Sethe about the infanticide reported in the news clipping, and she provides her justification (see above). Paul D is finally convinced that she did what she did, yet unconvinced it was the thing to do and a thunderhead of judgment issues the verdict: “You got two feet, Sethe, not four […] and right then a forest sprung up between them trackless and quiet” (1987: 194).[1] Paul D experiences something he cannot handle.

Standard empathy misfires as empathic distress. Standard empathy chokes on moral judgment. Paul D moves out of the house where he is living with Sethe, Denver, and Beloved. Standard empathy does not stretch into radical empathy. In a breakdown of empathic receptivity, Paul D takes on Sethe’s shame, and instead of a decision to talk about the matter with her, perhaps agreeing to exit the relationship for cause, Paul D runs away from both Sethe and his own emotional and moral conflicts, making an escape. Stamp blames himself for driving Paul D away by disclosing the infanticide to him (of which he had been unaware), and tries to go to explain it to Sethe. Seeking the honey of self-knowledge results in the stings of enraged distortion and disguise. Paul D finds the door is closed and locked against him. Relationships are in breakdown.

At this point the isolation of the women – Sethe, Denver, Beloved – inspires a kind of “mad scene” – or at least a carnival of emotion. Empathic interpretation occurs as dynamic and shifting points of view. The rapid-fire changing of perspectives occurs in the three sections beginning, “Beloved, she my daughter”; “Beloved is my sister”; “I am Beloved and she is mine” (Morrison 1987: 236; 242; 248). These express the hunger for relatedness, healing, and family that each of the women experience. For this reader, encountering the voices has the rhythmic effect of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. The voices are disembodied, though they address one another rather than the reader (as was also the case in Woolf). The first-person reflections slip and slide into a free verse poem of call and response. The rapid-fire, dynamic changing of perspectives results in the merger of the selves, which, strictly speaking, is a breakdown of empathic boundaries. There is no punctuation in the text of Beloved’s contribution to the back-and-forth, because Beloved is a phantom, albeit an embodied one, without the standard limits of boundaries in space/time such as are provided by standard punctuation.

This analysis has provided examples of empathic receptivity, understanding, and interpretation. One aspect of the process of empathy remains. In a flashback of empathic responsiveness: Sethe is on the run, having escaped enslavement at Sweet Home Plantation. She is far along in her pregnancy, alone, on foot, barefoot, and is nearly incapacitated by labor pains. A white girl comes along and they challenge one another. The white girl is named Amy Denver, though the reader does not learn that at first, and she is going to Boston (which becomes a running joke). What is not a joke is that Sethe and Amy Denver are two lost souls on the road of life if there ever were any. Amy is barely more safe or secure than Amy, though she has the distinct advantage that men with guns and dogs are not in hot pursuit of her. Sethe dissembles about her own name, telling Amy it is “Lu.” It is as if the Good Samaritan – in this case, Amy – had also been waylaid by robbers, only not beaten as badly as the man going up to Jerusalem, who is rescored by the Samaritan. Amy is good with sick people, as she notes, and practices her arts on Sethe/Lu. Sethe/Lu is flat on her back and in attempt to help her stand up, Amy massages her feet. But Sethe/Lu’s back hurts. In a moment of empathic responsiveness, Amy describes to Sethe/Lu the state of her (Sethe’s) back, which has endured a whipping with a raw hide whip shortly before the plan to escape was executed. Amy tells her:

“It’s a tree, Lu. A chokecherry tree. See, here’s the trunk – it’s red and spit wide open, full of sap, and this here’s the parting for the branches. You got a mighty lot of branches. Leaves, too, look like, and dern if these ain’t blossoms. Tiny little cherry blossoms, just as white. Your back got a whole tree on it. In bloom. What god have in mind I wonder, I had me some whippings, but I don’t remember nothing like this” (1987: 93).

This satisfies the definition of empathic responsiveness – in Amy’s description to Lu of what Amy sees on Lu’s back, Amy gives to Lu her (Amy’s) experience of the state of Lu’s back. Amy’s response to her (Lu) allows / causes Lu to “get” that Amy has experienced what her (Lu’s) experience is. Lu (Sethe) of course cannot see her own back and the result of the rawhide whipping which is being described to her. On background, early in the story, Sethe tells Paul D: “Them boys found out I told on em. Schoolteacher [actually a teacher, but mostly a Simon Legree type slave owner, and the brother of Mrs Garner’s late husband] made one open up my back, and when it closed it made a tree. It grows there still” (1987:20). The reader wonders, What is she talking about? “Made a tree”? The conversational implicature – clear to the participants in the story, but less so to the reader – lets the suspense – and the empathy – come out. The “tree” finally becomes clear in the above-cited passage. One has to address whether this attempt succeeds artistically to transform the trauma of the whipping into an artistic integration and transfiguration of pain and suffering. Nothing is lacking from Morrison’s artistry, yet the description gave this reader a vicarious experience of nausea, empathic receptivity, especially with the white puss. Once again, not for the faint of heart. This a “transfiguring” of the traumatic.

A further reflection on “transfiguring” is required. If one takes the term literally – transforming the figure into another form without making it more or less meaningful, sensible, or significant, then one has a chance of escaping the aporias and paradoxes into a state of masterful and resonant ambiguity. For example, in another context, when the painter Caravaggio (1571–1610) makes two rondos of Medusa, the Gorgon with snakes for hair, whose sight turns the viewer to stone, was he not transfiguring something horrid and ugly into a work or art? The debate is joined. The inaccessible trauma – what happened cannot be accurately remembered, though it keeps appearing in nightmares and flashback – is the inaccessible real, like Kant’s thing in itself. The performing of the trauma, the work of art – Caravaggio’s self-portrait as the Medusa[2] or the encounter of Amy and Sethe/Lu or Morrison’s Beloved in its entirety – renders the trauma accessible, expressible, and so able to be worked through, integrated, and transformed into a resource that at least allows one to keep going on being and possibly succeed in recovery and flourishing. Once again, the intention is a transfiguring of the traumatic. However, the myth of the Medusa itself suggests a solution, albeit a figurative one. In the face of soul murder embedded within moral trauma, the challenge to standard empathy is to expand, unfold, develop, into radical empathy. That does not add another feature to empathy in addition to receptivity, understanding, interpretation, and responsiveness, but it raises the bar (so to speak) on the practice of all of these. Radical empathy is committed to the practice of empathizing in the face of empathic distress. What does empathic distress look like? It looks like the reaction to the traumatic vision of the snake-haired Gorgon that turns to stone the people who encounter it. It looks like the tree on Sethe/Lu’s back, the decision that Sethe/Margarent should not have to make, but that she nevertheless makes, staring into her image of the Medusa, who show up as the four horsemen. This is to chase the trauma upstream in the opposite direction from the would-be artistic transfiguration. A

This points immediately to Nietzsche’s answer to Plato’s banning of tragic poetry from the just city (the Republic), namely, that humans cannot bear so much truth (1883: §39):

“Indeed, it might be a basic characteristic of existence, that those who would know it completely would perish, in which case the strength of a person’s spirit would then be measured by how much ‘truth’ he could barely still endure, or to put it more clearly, to what degree one would require it to be thinned down, shrouded, sweetened, blunted, falsified.“

And again, with admirable conciseness, Nietzsche (1888/1901: Aphorism 822): “We have art, lest we perish of the truth.” Here “truth” is not a semantic definition such as Davidson’s (1973, 1974) use of Tarksi (loosely a correspondence between language and world), but the truth that life is filled with struggle and effort—not fair—that not only are people who arrive early and work hard all day in the vineyard paid a full day’s wages, but so are people who arrive late and barely work also get paid a full day’s wages; that, according to the Buddha, pain is an illusion, but when one is sitting in the dentist chair, the pain is a very compelling illusion; not only old people get sick and die, but so do children. While the universe may indeed be a well-ordered cosmos, according to the available empirical evidence, the planet Earth seems to be in a local whorl in its galaxy where chaos predominates; power corrupts and might makes right; good guys do not always finish last, but they rarely finish first, based alone on goodness.

On background, the reader may recall that the hero Perseus succeeded in defeating this Medusa without looking at her. Anyone who sees the Medusa straight on is turned to stone. Perseus would have been traumatized by the traumatic image and rendered an emotional zombie – lacking in aliveness, energy, strength, or vitality – turned to stone. Beyond empathic unsettlement and empathic distress, moral trauma (moral injury) and soul murder stop one dead – not necessarily literally but emotionally, cognitively and practically. That is the challenge of the paradox and seeming contradiction: how to continue empathizing in the face of empathic distress. Is there a method of continuing to practice empathizing in the face of such distressing unsettlement? At least initially, the solution is a narrative proposal. Recall that Perseus used a shield, which was also a magic reflective mirror, indirectly to see the Medusa as a reflection without being turned to stone and, thus seeing her, being able to fight and defeat her. The shield acted as a defense against the trauma represented by the Medusa, enabling Perseus to get up close and personal without succumbing to the toxic affects and effects. There is no other way to put it – the artistic treatment of trauma is the shield of Perseus. It both provides access to the trauma and defends against the most negative consequences of engaging with it. The shield does not necessarily render the trauma sensible or meaningful in a way of words, yet the shield takes away the power of the Gorgon/trauma, rending it unable to turn one to stone. In the real-world practice of trauma therapy, this means rendering the trauma less powerful. The real world does not have the niceness of the narrative, where the Gorgon is decapitated – one and done! One gradually – by repeated working through – gets one’s power back as the trauma shrinks, gets smaller, without, however, completely disappearing. The trauma no longer controls the survivor’s life.

The question for this inquiry into Beloved is what happens when one brings literary language, refined language, artistic language, beautiful language, to painful events, appalling events, ugly events, dehumanizing events, traumatic events? The literary language has to dance around the traumatic event, which is made precisely present with expanded power by avoiding being named, leaving an absence. The traumatic events that happened were such that the language of witnessing includes the breakdown of the language of witnessing. As Hartman notes in his widely quoted study:

It is interesting that in neoclassical aesthetic theory what Aristotle called the scene of pathos (a potentially traumatizing scene showing extreme suffering) was not allowed to be represented on stage. It could be introduced only through narration (as in the famous recits [narrative] of Racinian tragedy) (Hartman 1995: 560 ftnt 30).

The messenger arrives and narrates the awful event, which today in a streaming series would be depicted in graphic detail using special effects and enhanced color pallet. One might say that Sophocles lacked special effects, but it is that he really “got it” – less is more. The absence of the most violent defining moment increases its impact. Note this does not mean – avoid talking about it (the trauma). It means the engagement is not going to be a head on encounter and attack, but a flanking movement. In the context of narrative, this does not prevent the reader from engaging with the infanticide. On the contrary, it creates a suspense that hooks the reader like a fish with the rest of the narrative reeling in the reader. The absence makes the engagement a challenge, mobilizing the reader’s imagination to fill in the blank in such a way that it recreates the event as a palpable vicarious event. It is necessary to raise the ghost prior to exorcising it, and the absentee implication does just that.

If this artistic engagement with trauma is not “writing trauma” in LaCapra’s sense, then I would not know it:

“Trauma indicates a shattering break or caesura in experience which has belated effects. Writing trauma would be one of those telling after-effects in what I termed traumatic and post-traumatic writing (or signifying practice in general). It involves processes of acting out, working over, and to some extent working through in analyzing and ‘giving voice’ to [it] [. . . ] – processes of coming to terms with traumatic ‘experiences,’ limit events, and their symptomatic effects that achieve articulation in different combinations and hybridized forms. Writing trauma is often seen in terms of enacting it, which may at times be equated with acting (or playing) it out in performative discourse or artistic practice” (LaCapra 2001: 186–187).

If the writing (and reading) of the traumatic events is a part of working through the pain and suffering of the survivors (and acknowledging the memory of the victims), then the result for the individual and the community is expanded well-being, expanded possibilities for aliveness, vitality, relatedness, and living a life of satisfaction and fulfillment. Instead of being ruled by intrusive flashbacks and nightmares, the survivor expands her/his power over the events that were survived. This especially includes the readers engaging with the text who are survivors of other related traumatic events, dealing with their own personal issues, which may be indistinguishable from those of fellow-travelers in trauma. That is the situation at the end of Beloved when Paul D returns to Sethe and Denver (Sethe’s daughter) after the community has exorcised the ghost of Beloved. It takes a village – a community – to bring up a child; it also takes a village to exorcise the ghost of one.

References

Anonymous. (2012). Trolley problem (The trolley dilemma). Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem [checked on 2023-06-25]

Hannah Arendt. (1970). On Violence. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Caty Caruth. (1996). Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Donald Davidson. (1974). On the very idea of a conceptual scheme. In Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 2001: 183–198.

Geoffrey H Hartman. (1995). On Traumatic Knowledge and Literary Studies New Literary History , Summer, 1995, Vol. 26, No. 3, Higher Education (Summer, 1995): 537 – 563 .

Martin Heidegger. (1927). Being and Time, John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (trs.). New York: Harper and Row, 1963.s

Albert R. Jonsen and Stephen Toulmin. (1988). The Abuse of Casuistry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dominick LaCapra. (1999). Trauma, absence, loss. Critical Inquiry, Summer, 1999, Vol. 25, No. 4 (Summer, 1999): 696–727

Dominick LaCapra. (2001). Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore, John Hopkins Unviersity Press.

Stephen Levinson. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toni Morrison. (1987). Beloved. New York: Vintage Int.

Friedrich Nietzsche. (1883). Thus Spoke Zarathustra, R. J. Hollingdale (tr.). Baltimore: Penguin Press, 1961.

________________. (1888/1901). The Will to Power, R. J. Hollingdale (tr.). New York: Vintage, 1968.

Ruth Leys. (2000). Trauma: A Genealogy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Boris Sagal, Director. (1981). Masade. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masada_(miniseries) [checked on 2023-06-25).

J. Shay, (2014). Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036090

Leonard Shengold. (1989). Soul Murder Revisited: Thoughts About Therapy, Hate, Love, and Memory. Hartford: Yale University Press.

Bessel van der Kolk. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Penguin.

[1] For those readers wondering how Sethe regained her freedom after being arrested for murder (infanticide), Beloved provides no information as to the sequence. During the historical trial an argument was made that as a free woman, Margaret Garner should be tried and convicted of murder, so that the Abolitionist governor of Ohio could then pardon her, returning here to freedom. Something like that needs to be understood in the story, though it is a fiction. It is a fiction, since in real life, Garner and her children were indeed returned to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Act. Moral trauma within soul murder indeed.

[2] Caravaggio was a good looking fellow, and he uses himself as a model for the face of the Medusa. This does not decide anything. Arguably, Caravaggio was arguably memorializing – transfiguring – his own life traumas, which were many and often self-inflicted as befits a notorious manic-depressive.

© Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

How I changed my relationship with pain

Expanded power over pain is a significant result that may usefully be embraced by all human beings who experience pain – which describes just about everyone at some time or another. Acute pain communicates an urgent need for intervention; chronic pain is demoralizing and potentially life changing. Intervention required!

People who do not experience standard amounts of pain are at risk of hurting themselves. Dr. James Cox, senior lecturer at the Wolfson Institute for Biomedical Research at University College London, notes, “Pain is an essential warning system to protect you from damaging and life-threatening events” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat2019)). Admittedly not experiencing pain is a rare and concerning condition from which few of us suffer. Hence the practical approach considered here for the rest of humanity.

I changed my relationship to pain by working on the relationship. The result is that less pain occurs in my life and the pain that I do experience does not dominate my life. If one is completely pain-free, one is probably dead, which has different issues.

The following behaviors made a difference. Regular exercise, healthy diet, spiritual discipline (I have trained extensively in Tai Chi, but Yoga and/or meditation encompass the same results), consultations with professionals of one’s choice including medical doctors; and, here is the wild card, the purpose of this post: education in the different types of pain, including but not limited to acute pain versus chronic pain. The reader may say, “Holy cow! That’s too much work!” However, if the reader is in enough pain, then consider the possibility. What’s the alternative? Continue to suffer? Medically assisted suicide (where legal)? Opioids? The latter in particular have a place in hospice (end of life scenarios), in the week after surgery, but otherwise they are a deal with the devil. And, in any deal with the devil, be sure to read the fine print. “At a time when about 130 American die daily from opioid overdoses, scientists and drug companies are actively pursuing alternative non-opioid medications for acute and chronic pain” (Jacquelyn Corley (Stat 2019)).

An example will be useful. I changed my relationship to pain, following my MDs guidance, by taking a double dose of NSAIDs – non steroidal anti-inflammatory “pain killers”. The idea is to “kill” the pain without killing the patient. This is no joke because NSAIDs such as Aleve can damage the mucous membranes of the gastro intestinal track (e.g., stomach), leading to ulcer-like conditions and the accompanying risks (not detailed here), which is why, even though they are over-the-counter, consultation with a medical doctor is important.

Doing Tai Chi changed my relationship to pain. Your mileage may vary, but I started to see results after ten weeks of dedicated daily work. My Tai Chi training has continued with one lengthy interruption for six years. My experience was the practice moved the pain threshold up. That is, I did not experience pain as acutely and when I did experience pain, it did not bother me as much. This can be a double-edged consideration. For example, the Tai Chi exercise of “holding the ball” is a stress position. One really needs a picture to see what this is.

One stands there with one’s arms encompassing a large ball at about the level of one’s chest with one’s hips tucked slightly as if sitting back. One’s whole body is engaged and conditioned. After about ten minutes one starts to heat up and after about fifteen minutes one starts to sweat. This is Tai Chi, not Yoga, but Mircea Eliade discusses similar stress positions that generate Shamanic Heat (Eliade, (1964), Shamanism, translated Willard Trask. Princeton University Press (Bollingen)).

Now a word of caution regarding the pain threshold. I went for a dermatological treatment and I got burned, literally, (fortunately, not too seriously), because I did not say “Stop – it hurts!” Granted that most people want to experience less pain, it is important to not extinguish pain completely, because pain in its acute presentation is trying to tell one something – in this case, injury to one’s skin due to heat.

Here is another example. A colleague has an inflamed ankle. It throbs. It hurts. It is not fractured but imaging shows it is enflamed, stressed out. The thing is that this is not just the person’s sprained ankle – it is his whole life. Since he needs to lose weight, he needs to get exercise. Because he cannot get sufficient exercise, he cannot lose weight. The extra weight contributes to the ankle continuing to be stressed. Double-bind! Rock and the hard place. How is this individual going to break out of this tight loop? Now I know this is going to sound crazy, but here it is: Follow doctor’s orders! Go to the physical therapy! If you have got to wear “the boot” for a couple of weeks, do so. Start low (with the number of repetitions of exercises) – go slow. If the person had access to a swimming pool, that would be ideal, but that might not be workable for many people. SPA-like treatments, soaks in Epsom salts in sensory deprivation pods have value.

Many parallel examples can be cited in which a person knows exactly what she has to do (don’t even worry about the doctor) – why is the person not doing it? Many reasons exist, but one of them is that suffering becomes a comfort zone. Suffering is sticky. “Yes, I am miserable,” the individual says, but it is a familiar misery. Suffering has become an uncomfortable comfort zone. What would it take to give that up? Once one realizes, “This is what crazy looks like,” it becomes easier to give up the suffering. This is not a deep dive into the psychology of the unconscious, yet this is not merely a physical challenge. Yes, the ankle hurts – objectively, there is even an image that shows inflammation, albeit hazy and faint. However, even if there weren’t evidence of an injury – and soft tissue damage often escapes imaging, the emotional issue – ambivalence about one’s body image (“weight”) – gets entangled with the person’s whole life. In this case, a struggle with unhealthy excess weight – and the person’s emotions run with the ball – elaborate the injury psychologically. This is also a form of catastrophizing or awfulizing (made famous by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)), but CBT did not invent it.

I gave the example of an inflamed ankle, but it might also apply to lower back pain, headaches, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which are notoriously difficult to diagnose medically. Speaking personally, I want a quick fix. We all do. However, after a while, if the “fix” does not occur, there is no in principle limit on the amount of time and effort one can spend trying to find a quick fix. After a certain time, one gets a sense that one might put the time and effort into incremental progress – finding whatever moves the dial – whatever shifts the stuckness. Here’s what I did not want to hear: This is gonna take some work. After a time, one decides to roll up the sleeves and do the hard work need to get one’s power back. Healthy diet and a well-defined exercise program are important components. Finding an MD and/or health care provider including physical therapist where the interpersonal chemistry works is on the critical path to dialing down the suffering. Here “interpersonal chemistry” is another description for empathy. Look for someone whose empathy is open enough to encompass one’s pain and suffering without being coopted by it. This is the critical path to recovery.

The distinction between acute pain and chronic pain needs to be better understood by the average citizen. An excerpt from Neurology 101 may be useful. In acute pain, the peripheral nervous system in the body’s appendages such as one’s toes reports via neural connections to the central nervous system (e.g., the brain in one’s head). The impact of a heavy object such as a large brick with my toe releases neurotransmitters at the nociceptors (we are not talking Greek and “nocio” means “pain”). The mechanics are such that a message is delivered from the periphery to the center that what is in effect a boundary violation – an injury – has occurred. The brain then tells the toe to hurt – “Ouch!” The message is delivered seamlessly to the conscious person to whom the toe “belongs” in the neural map that associates the body with conscious experience unfolding in the person’s awareness. The toe which had quietly been doing its job in helping the person walk, balance, be mobile now makes a lot of “noise” – it starts throbbing. This is what acute pain feels like.

With chronic pain the scenario gets complicated. If the injury is subjected to other stressors, slow to heal, reinjured, or otherwise neglected, then the pain may continue across a period of days or weeks and become habitual. In effect, the pain signal becomes a bad habit. The pain takes on a life of its own. What does that even mean? What starts out as a way of reminding the person to attend to the injury gets stuck on “repeat”. Like the marketing company that keeps sending your notices even after you specify “Do not solicit!” The messaging is not just from the toe to the brain, from the periphery to the center, but it gets reversed. The messaging is from the center to the periphery, from the brain to the body part. The brain tells the periphery to hurt. Chronic pain becomes a source of suffering. Here “suffering” expands to include worry that anticipates and/or expects pain, which gets further reinforced when the pain actually shows up.

The poster child for chronic pain is phantom limb pain. Not all pains are created equal. Phantom limb pain provides compelling evidence that pain is “in one’s head” only in the sense that pain is in the brain and the brain is in one’s head. Only in that limited sense is pain in one’s head. Yet the pain is not imaginary. Documented as early as the American Civil War by Silas Weir Mitchell, individuals who had undergone amputation, felt the nonexistent, missing limb to itch or cramp or hurt. The individuals experienced the nonexistent tendons and muscles of the missing limb as cramping and even awakening the person from the most profound sleep due to pain (As noted, further in Haider Warraich. (2023). The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain. New York: Basic Books, pp. 110 – 111).

Fast forward to modern times and Ron Melzack’s gate control theory of pain marshals such phantom limb pain as compelling evidence that the nervous system contains a map of the body and the body’s pains point, which map has not yet been updated to reflect the absence of the lost limb. In effect, the brain is telling the individual that his limb is hurting using an obsolete map of the body – the memory of pain. Thus, the pain is in one’s head, but not in the sense that the pain is unreal or merely imaginary. The pain is real – as real as the brain that is indeed in one’s head and signaling (“telling”) one that one is in pain. (R. Melzack, (1974), The Puzzle of Pain. Basic Books.)

Whatever the level of pain, stress is probably going to make it feel worse. Therefore, stress reduction methods such as meditation, Tai Chi, Yoga, time spent soaking in a sensory deprivation pod, and SPA-like stress reduction methods are going to be beneficial in moving the pain dial downward.

One question that has not even occurred to scientists is whether it is possible to have the functional equivalent of phantom limb pain, even though the person still has the limb functionally attached to the body. This sounds counter-intuitive, but think about it. If there is a map of the body’s pain points in the central nervous system (the brain), there is nothing that says “phantom” pains cannot occur even if an appendage still exists. For example, the high school football player who needs the football scholarship to go to college because he is weak academically; he is not good at baseball, but actually hates football. He incurs a soft tissue sports injury, which gets elaborated due to emotional conflict about his ambivalent relationship with football, leaving him on crutches for far-too-long and both physically and symbolically unable to move forward in his life. As if the only three life choices are football, baseball, and academics?! Note that the description of the injury “painful soft tissue” already opens and shuts approaches to treatment. That is the devilish thing – what is the actual and accurate description? Thus, due to the inherent delays in neuroplasticity – the update to the brain’s map of the body is not instantaneous and one does not have new experiences with a nonexistent limb – pain takes on a life of its own.

Though an oversimplification, the messaging between the peripheral and central nervous systems is reversed. Instead of the peripheral limb telling the brain of a “hurt,” the brain develops a “bad habit” of signaling pain and tells the limb to hurt. That is the experience of chronic pain – pain has a life of its own – pain becomes the dis-ease (literally), not the symptom. What then is the treatment, doctor? Physical therapy (PT) – exercises to strengthen the knee and, in effect, teach him to walk again.

Chronic pain is discouraging, demoralizing, fatiguing, exhausting, negatively impacting one’s mental status. I have been cagey about my own experience of pain in this post, but it is a matter of record that I have osteoarthritis, a progressive deterioration of the cartilage in joints such as occurs in people who are getting older and who are long term runners. The person understandably and properly continuously asks himself – what am I experiencing? And does it include pain? No one is saying the “cure” is don’t think about it (pain), don’t worry about it. No one is saying “play hurt”? “Playing hurt” is a bad idea for so many reasons, including one is going to make a bad injury worse. Professional athletes who “play hurt” may indeed get a bunch of money, but they also often dramatically shorten their careers – and that costs them money.

While distraction from one’s pain can be useful in the short term, it is not a sustainable solution. Rather when, after medical determination of the sources of pain are determined to be unable to be completely extinguished or eliminated, one is saying undertake an inquiry into what one is really experiencing. Rather than react to the uncomfortable twinges and twitches, bumps and thumps, prodding and pokes, that one encounters, ask what one is really feeling. Undertake an inquiry into what one is experiencing. If, upon consideration, the answer is “The pain is acute going from 4 to 8 to 9 on the 10 point scale,” then stop and call for backup, including taking pain killers such as NSAIDS as recommended by an MD.

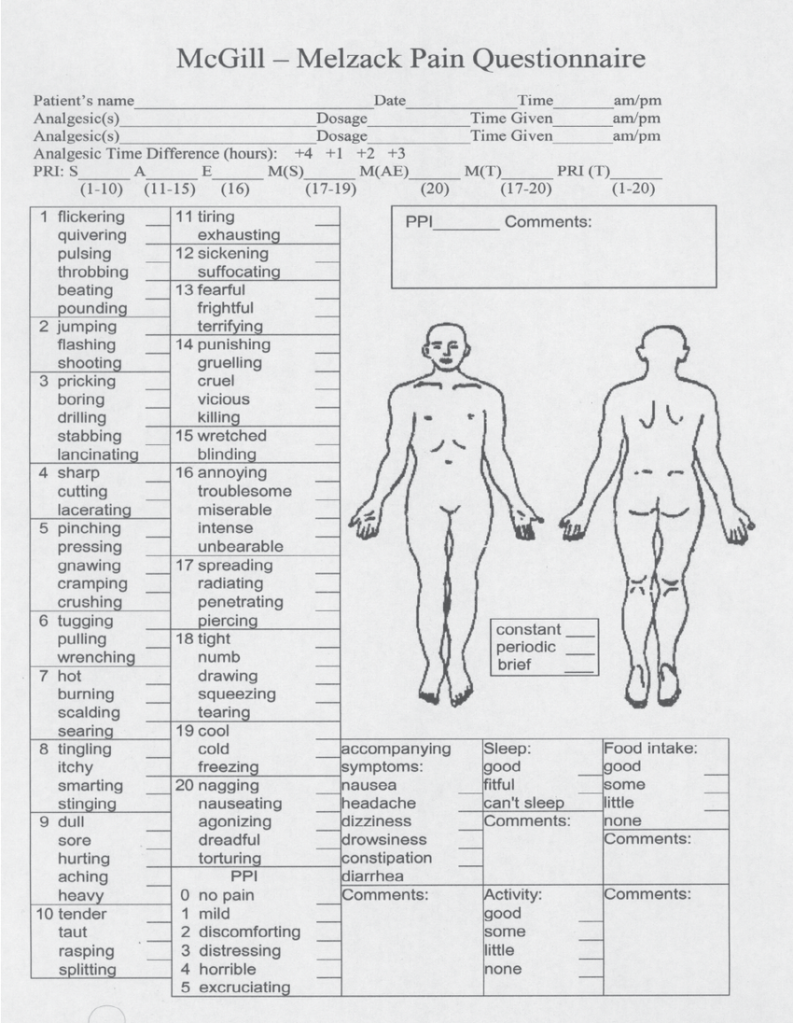

Here the vocabulary of pain is relevant. See Melzack’s McGill pain chart. [List the vocabulary]

Further background information will be useful. Haider Warraich, MD, in The Song of Our Scars: The Untold Story of Pain (Basic Books, 2023) radicalizes the issue of pain that takes on a life of its own before suggesting a solution. After providing a short history of opium and morphine and opioids, culminating “in the most prestigious medical school on earth, from the best teachers and physicians, we [medical students] were unknowingly taught meticulously designed lies” (p. 185), that is, prescribe opioids for chronic pain. The reader wonders, where do we go from here? To be sure opioids have a role in hospice care and the week after surgery, but one thing is for certain, the way forward does not consist in prescribing opioids for chronic pain.

After reviewing numerous approaches to integrated pain management extending from cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) to valium, cannabis and Ketamine – and calling out hypnosis (hypnotherapy) as a greatly undervalued approach (no external chemicals are required, but the issue of susceptibility to hypnotic suggestibility is fraught) – Dr Warraich recovers from his own life changing back injury in a truly “physician heal thyself” moment thanks to dedicated PT, physical therapy (p. 238). If this seems stunningly anti-climactic, it is boring enough to have the ring of truth earned in the college of hard knocks, but it is a personal solution (and I do so like a happy ending!), not the resolution of the double bind in which the entire medical profession finds itself (pp. 188 – 189). The way forward for the community as a whole requires a different, though modest, proposal. The patient signs up for and completes physical therapy (PT), a custom set of exercises tailed to his pain condition and mobility issues.

The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote, “The body is the best picture of the soul.” The default since René Descartes is to distinguish physical pain from psychic pain – what used to be called the difference between “body” and “soul” before science “proved” that the soul did not exist. (Once again, we are talking Greek “psyche” is the Greek word for “souI.”) Nevertheless, in spite of the “proof” that the soul does not exist, soul-like phenomena keep showing up. For example, if the person’s “soul” is regularly subjected to negative verbal feedback from those in authority, the person becomes physically ill – ulcers, headaches, lower back pain, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). As noted, these are notoriously difficult to diagnoses. The adverse childhood experience survey (ACE) provides solid evidence that psychic and moral injuries correlate significantly with major medical disorders (e.g., Felitti 2002).

One big issue is that we (science and scientists) lack a coherent, effective account of emergent properties. One with neurons. The alternative is the current reductive paradigm according to which, in spite of contrary assertions, on has trouble explaining that things really are what they seem to be – that table are tables andmade of microscopic components such as atoms. We start with neurons. We are neurons “all the way down.” Neurons generate stimuli; stimuli generate sensations/experiences; experiences generate [are] responses; responses form patterns; patterns generate meaning; meaning generates language. With the emergence of language, things really start to get interesting. Organized life reaches “take off” speed. Language generates community; community generates – or rather is functionally equivalent to – culture, art, poetry, science, technology, and the world as we know it.

What about individuals who are put in a double-bind by circumstances as when someone in authority makes a seemingly impossible demand? For example, the army Sargent gives what seems to be a valid military order to the corporeal to shoot at the rapidly approaching auto, thinking it is a suicide car bomb, but it is really an innocent family. The soldier, thinking the order is valid and that he is protecting his team, follows the order. The solider is now both a perpetrator and a survivor. People have gotten hurt who ought not to have been hurt. Moral inquiry. Moral trauma has occurred. Tai Chi is not going to save this guy. This take the form of guilt – which is aggression – hostile feeling and anger – turned against one self. The individual’s agency – the individual’s power as an agent to choose – is compromised by contingent circumstance, including the individual’s unavoidable choice in the circumstance, since taking no action is also a choice.

This is why the ancient Greeks invented tragedy. A careful reading of the Greek tragedies, which cannot be adequately canvassed here, shows that virtually every tragic hero has the compromised agency characteristic of a double bind. Oedipus is a powerful agent, yet compromised and brought low by inadequate information. Information asymmetries! Antigone’s agency is bound, doubly, by the conflict between the imperatives of politics and the integrity of family. Agamemnon’s agency is compromised by the negative aspect of honor and pride and an overweening narcissism. Iphigenia’s agency is compromised by literally being bound and gagged (admittedly a limit case). Double-binds have also been hypothesized to contribute to the causation of major mental illness (Bateson 1956). Contradictory messages from parents, explicit versus implicit, spoken versus unspoken, are particularly challenging. Here the fan out to related issues is substantial.

I changed my relationship to pain and suffering by reading all thirty existing Greek tragedies. One might say if something is worth doing, it is worth over-doing, and the reader might try starting with just one. Examples of pain and suffering occur in abundance: acute pain – Hercules puts on the poisoned cloak, which burns his flesh; chronic pain – Philoctetes has a wound that will not heal and throbs periodically with painful sensations; and suffering – Oedipus is misinformed about who is his birth mother and after having children with her he suffers so from his awareness of his violation of family standards that he mutilates himself, tearing his eyes out. The latter would, of course, be acute pain, but the cause, the trigger, is thinking about what he has done in relation to the expectations of the community, namely, violating the incest taboo.

Now, according to Aristotle, the representation of such catastrophes is supposed to evoke pity and fear in the audience (viewer) of the classic theatrical spectacle. Indeed, such spectacles – even though the violence usually happens “off stage” and is reported – are not for the faint of heart. We seem to want to identify with the characters in a narrative, which, in turn, activates our openness to their experiences in an entry level empathy that communicates a vicarious experience of the character’s struggle and suffering. Advanced empathy also gets engaged in the form of appreciation of who is the character as a possibility in relation to which the viewer (audience) considers what is possible in her of his own life. One takes a walk in the other’s shoes, after having taken off one’s own. Other examples of similar experiences include why (some) people like to see horror movies. One does not run screaming from the theatre, but conventionally appreciates that the experience is a vicarious one – an “as if” or pretend experience. Likewise, with “tear jerker” style movies – one gets a “good cry,” which has the effect of an emotional purging or cleansing.

Now I am not a natural empath, and I have had to work at expanding my empathy. In contrast, the natural empath is predisposed, whether by biology or upbringing (or both), to take on the pain and suffering of the world. Not surprisingly this results in compassion fatigue and burn out. The person distances him- or herself from others and displays aspects of hard-heartedness, whereas they are actually kind and generous but unable to access these “better angles.” It should be noted that empathy opens one up to positive emotions, too – joy and high spirits and gratitude and satisfaction – but, predictably, the negative ones get a lot of attention.

“Suffering” is the kind of thing where what one thinks and feels does make a difference. Now no one is saying that Oedipus should have been casual about his transgressions – “blown it off” (so to speak); and the enactment does have a dramatic point – Oedipus finally begins to “see” into his blind spot as he loses his sight. Really it would be hard to know what to say. Still, the voice of reality would council alternatives – other ways are available of making amends – making reparations – perhaps more than two “Our Fathers” and two “Hail Marys” as penance – what about community service or fasting? “Suffering” is not just a conversation one has with oneself about future expectations. It is also a conversation one has with oneself about one’s own inadequacies and deficiencies (whether one is inadequate or not). For example, unkind words from another are hurtful. In such cases what kind of “pain” is the hurt? We get a clue from the process of trying to manage such a hurt. The process consists in setting boundaries, setting limits, not taking the words personally (even though inevitably we do). The hurt lives in language and so does the response. Therefore, in an alternative scenario, one takes the bad language in and turns it against oneself. One anticipates a negative outcome. One gets guilt (once again, regardless of whether one has does something wrong or not).

The coaching? If you are suffering from compassion fatigue, then dial down the compassion. This does not mean become hard-hearted or mean. Far from it. This means do not confuse a vicarious experience of pain and suffering with jumping head over heels into the trauma itself. What may usefully be appreciated is that practices such as empathy, compassion, altruism are not “on off” switches. They are not all or nothing. Skilled executioners of these practices are able to expand and contract their application to suit the circumstances. To be sure, that takes practice. The result is expanded power over vicariously shared pain and suffering. One gets power back and is able to assist the other in recovering their power too. (Further tips and techniques on how to change one’s thinking and expand one’s empathy are available in my Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide (with 24 full color illustrations by Alex Zonis), also available as an ebook.)

Before concluding, I remind the reader that “all the usual disclaimers.” This is a personal reflection. The only data is my own experience and bibliographical references that I found thought provoking. “Your mileage may vary.” If you are in pain (which, at another level and for many spiritual people, is one definition of the human condition) or if you are in the market for professional advice, start with your family doctor. If you do not have one, get one. Talk to a spiritual advisor of your own choice. Above all, “Don’t hurt yourself!” This is not to say that I am not a professional. I am. My PhD is in philosophy (UChicago) with a dissertation entitle Empathy and Interpretation. I have spent over 10K hours researching and working on empathy and how it makes a difference. So if you require expanded empathy, it makes sense to talk to me. A conversation for possibility about empathy can shift one’s relationship with pain.

Bibliography

Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J., 1956, Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, Vol. 1, 251–264.

Corley, Jacquelyn. (2019). The Case of a Woman Who Feels Almost No Pain Leads Scientists to a New Gene Mutation. Scientific American. March 30, 2019. Reprinted with permission from STAT. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-case-of-a-woman-who-feels-almost-no-pain-leads-scientists-to-a-new-gene-mutation/

Eliade, Mircea. (1964). Shamanism. Princeton University Press (Bollingen).

Felitti VJ. (2002). The Relation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead. The Permanente Journal (Perm J). 2002 Winter;6(1):44-47. doi: 10.7812/TPP/02.994. PMID: 30313011; PMCID: PMC6220625.

Melzack, R. (1974). The Puzzle of Pain. New York: Basic Books.

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project