Home » 2020

Yearly Archives: 2020

Review: From Passions to Emotions

I am catching up on my reading this holiday season, and by far the most incisive and penetrating work on the emotions that I have read all year is this one, From Passions to Emotions, by Thomas Dixon. It is an eye-opening work of vast learning and scholarship. Now for some readers of this blog the advanced level of scholarship may be a turn-off (and there is nothing wrong with that!), nor is this a “how to” book with tips and techniques; still, I found Dixon stimulating and engaging in his coverage of perspectives on the emotions of which I had previously been unaware. I came away thinking, “This guy has read everything.” Short review: Two Thumbs Up. The longer review follows.

I was immediately engaged to learn that the word “emotion” did not even exist in the English language prior to the 18th Century. The English philosopher David Hume (1711 – 1776) spent three years in France writing his A Treatise on Human Nature (1739). There Hume encountered Rene Descartes’ (1596 – 1650) The Passions of the Soul (1649). The latter makes use of the French word émotion, the probable source for Hume’s “emotion. ” Descartes and Hume are the likely source of the further dissemination of “emotion” in the Scottish Enlightenment. Still, “emotion” is lightly used in Hume’s text, which favors references to “passion” and “affection” in talking about what we today regard as emotions. The meanings are dynamic. They start to spin.

For example, the meaning of the word “passion” itself has shifted from referring to the suffering of the Christian fall from grace and redemption from sin to the mechanical transformation of animal spirits and perceptions in René Descartes’ writings. The word “science” shifted from meaning the systematic inductive inquiry into all aspects of reality using introspection to the limited search for physical causes. “Nature” means the opposite of “grace” in a Christian context but the opposite of “social” or “man-made” in the context of Scottish moralists. “Will” could mean an aspect of the soul created by God, ungoverned appetites, or, in contrast, a feeling resulting from nervous activity.

Things really get going in the 1800s with a large group of Christian, theistic, and introspective thinkers of whom few readers today has ever heard and whom few actually read. For example, today few engage with Isaac Watts, Jonathan Edwards, Thomas Reid, James McCosh, William Lyall, or George T. Ladd. Ladd had been a Christian minister and teacher for ten years before turning to psychology.

One point that Dixon repeatedly notes is that there is no inherent inconsistency in being a Christian or theist and doing serious scientific work; it is just that the meaning of “science” itself has changed significantly from such “sciences” as theology, church history, and the study of revelation to secular disciplines such as chemistry, biology, physics – and psychology. For example, Charles Bell is best know for Charles Darwin’s (1809 – 1882) opposition to his theistic religious commitments to a monistic (not historical) designer of the universe. Bell is also known for his serious work in physiology, anatomy, and as the identifier of “Bell’s palsy.” And yet…

Far from being the start of the use of the word “emotion,” as is frequently maintained in psychology textbooks today, Charles Darwin’s book [The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872)] and William James’s essay [“What is an Emotion?” (1884)] are the culmination of a long tradition and debate. Of course, it remains true that the end of one era is the beginning of another, and Darwin’s and James’ works were, each in their own way, highly innovative contributions.

Today we forget – or never knew – what a large role organized religion played in academic and scientific circles in the 18th and 19th centuries. One could not even be chosen as a professor at the University of Edinburgh without being a member of the clergy. Thomas Brown (1778 – 18820), whose Lectures on the Philosophy of the Human Mind(1820), was responsible for the breakthrough in putting the distinction “emotion” on the academic and scientific map(s), was initially refused appointment as a professor because he was merely a medical doctor, not a cleric. Indeed Dixon considers Brown to be “the inventor of the emotions” as a conceptual distinction (p. 109). Brown died in 1820, and by 1860 his book had gone through some 20 editions. Impressive. Today, except for Dixon, we would not know of Thomas Brown’s enormous influence.

One “Ah ha” moment among many for me as a reader of Dixon was that “emotion” has come to include such strong and disruptive passions as anger, fear, sadness as well as delicate and fine-grained affections such as fondness for one’s children, warm feelings towards friends, appreciation of music and visual art, or love of God (if one is so inclined).

Thus, “emotion” has legs on both sides of the mind-body distinction with the fine-grained affections such as love of wisdom and God that Saints Augustine and Aquinas saw as an essential part of the soul migrating in the course of history to a third, stand-alone, faculty – sometimes called the faculty of judgment, [aesthetic] taste, or simply affectivity – alongside cognition and volition. For example, the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s approach to the finer feelings and affects actually gets subordinated to his theory of aesthetic taste of the beautiful and sublime.

In terms of contemporary debating points, Dixon initially pushes back against Paul Griffiths’ [What Emotions Really Are (1997)] detailed argumentS that “emotion” is not a natural kind, not even a family resemblance, but an ad hoc label for three diverse unrelated phenomena.

At the risk of oversimplification, in Griffiths, these three distinctions are “affect programs” such as basic anger, sadness, fear, high spirits (“happiness”), and a few others (as identified by Paul Ekman); reactive passions such as righteous indignation at unfairness (as identified by Robert H. Frank); and socially constructed conventions such as romantic love (see James Averill and Rom Harré). The net of it? “Emotion” is a kludge.

Griffiths is particularly at pains to provide counter examples to Anthony Kenny’s assertion that the defining characteristic of authentic emotions is their being a propositional attitude – being about some something or situation. Had the authorities read Griffiths carefully, this would have pulled the rug out from under the celebrated late Peter Goldie even before Goldie was published.

For example, the instances of cognitive impenetrability belong here: a person knows that flying is safer than driving, but he is still afraid of flying. A person knows the food is wholesome but the shape of the pasta still reminds him of grubs, which he finds disgusting. Dixon does not explicitly comment on the cognitive impenetrability of the emotions, but, as far as I read him, nothing Dixon says flat out contradicts Griffith.

And yet there is a long Christian tradition of affections being cognitive acts or volitional activities, including the highly cultivated love of the Creator, contemplation of the wonders of nature, appreciation of art, forms of friendship, fervent desire of virtue and the good, and so on.

Meanwhile, Charles Darwin – who studied to be a cleric after abandoning medical school (though he eventually ended up as a committed agnostic) – got himself entangled in intellectual knots in (1872) deciding to argue that emotions were vestigial behaviors (analogous to the appendix in man), which were neither expressive in the authentic, full sense nor adaptive. Not adaptive?

The scandal is that Darwin then had to fall back on the [Lamarckian] inheritance of acquired characteristics (not natural selection!) to account for the continuum between the “expression” of emotion in man and animals. Animals such as dogs and chimps were indeed expressing their emotions; but man was performing habitual behaviors without purpose that had taken on a fossilized life of their own in the species. The scandal grows as for Darwin the emotions are not expressive – they are vestigial gestures.

Dixon argues persuasively that Darwin’s work on the emotions took considerable pains to disagree with and refute Charles Bell’s assertion that the emotions were purposeful, showing us the wisdom of the ultimate designer of the clockwork universe, the God of the deists and quasi-Unitarians. Apparently the emotions could not be both purposeful and the work of Darwin’s own quasi-divine first principle of adaptation, natural selection.

While one may disagree with Darwin and even try to rationally reconstruct what makes sense in Darwin’s highly-nuanced position, Dixon makes the powerful point that the reader will never understand Darwin work on the emotions without engaging with the religious (theistic) dimension represented by Bell against whom Darwin was arguing.

The irony is that the emotions Darwin identified were purposeful in animals such as dogs and chimps, but no longer so in that higher animal, man. Darwin takes this position because, if such emotions were thus purposeful in man, it would show forth the wise hand of Bell’s theistic creator in furnishing such a subtle mechanism; whereas, in contrast, if the emotions in man had no purpose, but were vestigial behaviors, then Bell would be wrong and Darwin right.

This is par for the course. Dixon goes on to provide overwhelming scholarly evidence that “emotion” is used in a diversity of ways by Christian, theistic, introspective, physicalist, psychological, and physiological authors throughout the 19th century. In conclusion, Dixon both agrees and side-steps Griffiths that “emotion” is an “overly broad category,” without actually touching Griffiths’ position about emotion as a natural kind. Good enough?

William James (1842 – 1910) made an enduring splash in “What is an Emotion?” published in Alexander Bain’s journal Mind in 1884. James’ innovation was to assert that the conventional view of the emotions was exactly backwards. One thinks one endures a loss, feels sad, and then expresses the emotion by crying; one thinks one sees an angry bear, feels fear, and expresses the fear by taking flight are shaking with fear. But, James asserted, the causality is just the reverse: one endures the loss, one is overcome with visceral bodily experiences of crying, and only then does one experience the sadness. One sees the bear, experience visceral bodily awareness of trembling and taking off running, and only then does one experience fear. The triggering event and the visceral reaction precede the introspective awareness of what we come to call the emotion in question.

While powerful in its boldness, and perhaps applicable to those emotions that are most reflex-like in activating an immediate fight/flight physical response, James’ theory was immediately refuted by counter-examples and logical inconsistencies.

First, the relation between the emotion and its expression is not really causal. Fear or deep sadness are not to be distinguished from the flight reaction or melancholic flood that overtakes the individual. Sadness and its expression in crying are not causally related. The feeling and the expression are part of one and same behavioral-affective-expressive constellation.

Nor James’ theory differentiate between different emotions. For example extreme joy and intense grief are both accompanied by weeping. “Tears of joy” are a common place. Furthermore, worry and other form of cognitive expectation provide evidence that thinking about the circumstances that call forth an emotion actually do call it forth, providing an explicit counter-example to James’ proposed direction of causality.

According to Dixon, James’ compelling oversimplification is a major source of what Robert Solomon (The Passions: Emotions and the Meaning of Life (1993) – Dixon’s ultimate target) calls the myth of reason versus the passions. In working on rehabilitating a certain wisdom of the emotions, Solomon (and many others) overlook the contribution of many Christian thinkers – especially in the Scottish and English Enlightenments – that the affections are a significant source of wisdom.

It is “a bum rap” to accuse Christian philosophers and thinkers to set up an irreconcilable dichotomy here as Solomon does.

The kinder affections of neighborliness and the moral sentiments have been a solid part of the Christian canon at least since the Parable of the Good Samaritan. These get pushed down and pushed back in Solomon (and James). True, the war between the spirit and the flesh (and the latter’s sexual and aggressive tendencies) lives on. Human beings are a difficult species.

The emotions are much more than the disruptive passions such as appetite and desire and anger (and so on), since the emotions have come to include feelings of neighborliness, sentiments of kindness, pleasure in music and intellectual inquiry, and so on.

Joseph Butler (1692 – 1752), as much a deist as a Christian notwithstanding his critique of the former, argued persuasively against Hobbes’ war of all against all that people are as interested in others as they are interested in themselves. Whether other-interest is just a more refined form of self-interest continues to be debated, but there is no logical contradiction in the two reciprocally reinforcing one another. Results and success in commerce, business, science, and life require cooperation as well as competition.

“Emotion” has come to mean cognitive acts of the soul, phenomenal feelings reducible to either cerebral or visceral activity, socio-cultural phenomena that have displaced basic biology in the experience of community. Just as “phlogiston” [a supposed quantity of heat] of proto-chemical natural philosophy has been dropped from today’s scientific chemistry, the “passions and affections” of the soul no longer occur in psychological or physiological models. Yet the passions and affections of the soul cast a long shadow over our current psychological paradigms and the use of the word “emotion” in emotional language.

Narcissism gets a bad rap: On empathy and narcissism

Narcissism has gotten a bad name. “Narcissism” has become a euphemism – a polite description – for a variety of integrity outages and bad behaviors. These extend from antisocial, psychopathic actions through bullying and domestic violence all the way to bipolar spectrum disorders or moral insanity. “Narcissism” has become the label of choice when an individual is behaving like a jerk.

In the face of narcissism’s bad name, I am not here to give narcissism a good name, but rather I suggest the matter is more nuanced than that presented in the popular psychology press today. Like Mark Anthony commenting on Julius Caesar in his funeral oration after Caesar’s assassination, I come not to praise narcissism but to bury it – and to differentiate narcissism from more serious forms of bad behavior with which it is confused. This article suggests that if a person behaves in an anti-social, bullying, boundary violating or other problematic way described above, then narcissism is the least of the worries.

Whip-sawed as the narcissist is between arrogant grandiosity and vulnerable idealization, the authentic narcissist will reliably provide a positive developmental response to empathy. However, if repeatedly providing empathy to the alleged narcissist just gets you more manipulations, bullying, integrity outages, and broken agreements, then you may really be dealing with an anti-social person and personality, moral insanity, psychopathy, or undefined lack of integrity, in which case, empathy will not work. Neither will compassion. Limit setting is the order of the day. Fill out the police report and get the order of protection.

The truth of narcissism is that people need and use other people to regulate their emotions. When Elvis sang “I wanna be – your teddy bear” (Elvis Presley, that is), he was bearing witness to the truth that we use other people to sooth our distressed selves, provide emotional calming when we are upset, and give us the empathy we need to fell good about ourselves.

“I wanna be your teddy bear” means “I wanna give you the empathy, recognition, acknowledge that you need to feel good about yourself.” If the other person subsequently does not respond to you as a whole person, then that is surely a disappointment but the shortcoming is not necessarily in anything you did. The other person did not keep their commitment.

People want people who respond to them as a whole person. People want people who appreciate who they are as a possibility. People need that sort of thing. People are vulnerable to the promise of such satisfaction because it feels good when it actually shows up.

Of course, the big ifs contained in such a proposal are that the other person is capable of providing such empathy; the other person is reciprocally acknowledged as being someone from whom empathy is worth receiving, and then the other actually behaves in a way that is understanding and receptive.

If the other person expresses hostility, withholds acknowledgement, does not honor his or her word, perpetrates micro aggressions (“narcissistic slights”), manipulates in subtle and overt ways, or behaves in a controlling or dominating way, behaves like a bully, then is that narcissism? It might be – but it might also be a lack of integrity (dishonesty), anti-social personality behavior, criminality, boundary violations, and abuse. It might or might not be narcissism – but it is definitely behaving like a jerk [just to use a neutral, non vulgar term].

The person who survives such an encounter or relationship with the alleged psychopath in narcissistic sheep’s clothing then has two problems. The first problem is that the individual has been deceived, manipulated, or cheated. The second problem is that he or she blames himself.

Narcissists are supposed to be excessively self-involved, self-centered, self indulgent. To succeed in life, most people need to have a dose of healthy self confidence. By a show of hands, who reading this article lacks a strong sense of self-interest? Get some help with that. Okay – that’s narcissism, but not pathological narcissism.

When I read the latest denunciation of narcissism in the pop psychology magazine, I wonder where are all of these people who are not self-involved, self-centered, self-interested, looking out for “number one”?

I go to social media where self-expression is trending. My take-away? Freedom of speech and self expression are flourishing – no one is listening! Is such lack of listening narcissism? Perhaps. But more likely is not lack of listening rather just lack of listening? Lack of commitment of expanding listening skills, inclusiveness, and lack of community?

So suppose the popular press is all mixed up about narcissism. What does the disentangling of this mess look like?

People who are described as narcissists have [some] people skills. Even if one’s empathy is incomplete and defective at times, most people crave an empathic response and are able to provide one, at least on a good day. The challenge is that the narcissist’s empathy breaks down in emotional contagion, conformity, lack of perspective taking, and messages getting lost in translation.

Most people want to look good and avoid looking bad, and narcissists are especially prone to doing that. Most people are committed to being right and, while we theoretically acknowledge we might be wrong, few people actually behave that way. Most behave like “know it alls,” especially in areas about which they literally know nothing. Narcissists are especially prone to that too. So we are all narcissists now?

The differentiator is that the narcissist ends up feeling like a fake, experiencing an empty (not melancholic) depression, even in the face of authentic accomplishments.

Even when the narcissist actually performs and wins the gold ring, he (or she) still feels like a fake. There is a kind of empty depression, lack of energy, lack of vitality. This lack of aliveness may cause the narcissist arrogant, cold, haughty withdrawal or acting out using substances of abuse or sexual misadventures. In spite of actual accomplishments, the narcissist may feel that life is passing him by. A pervasive sense of lack of aliveness, vitality, or apathy dominates the narcissist’s emotional life.

The one thing that narcissism is not confused with is autism spectrum disorders. The narcissistic has access to empathy, values it, “gets” it, craves it, even if the narcissist’s empathy is distorted and incomplete. I speculate that the psychopath is good at faking empathy, like an empathy parrot, prior to his perpetrations, whereas the narcissist is just not very good at it. He may seem to be faking empathy, but that is his clumsy effort to get it right, which is not working.

It seems as though the narcissist has an exaggerated self worth and, if in a position of authority, has the power to enforce his or her distorted view on others. The narcissist shares his suffering in a bad way by causing pain and suffering to the people in his environment. When such a person has authority, the result indeed can be dysfunction behavior, which is hard to distinguish from bullying.

As with most forms of bad behavior, the optimal first response is to set a limit to the bad behavior by pushing back, calling it out, expressing concern, or using humor to deflect: such behavior (bullying, bad language, physical or financial abuse, etc.) is unacceptable. “That doesn’t work for me.” “Stop it.” Without establishing a context of safety and security, we do not have a set up for success in which empathy can make a difference. Few people are in a position to up and quit their job. No easy answers here. Depending on the seriousness of the situation, then document, call for backup, and escalate to the authorities, including a call to 911 or a police report as applicable.

At this point, the narcissist may get the idea, “Hey maybe I need someone to talk to – professionally.”

While every case is different, no one size fits all, and all the usual disclaimers apply, the intervention with the narcissist often consists in a conversation for possibility. Talk to the person. Give him or her a good listening, and she what shows up. The person’s experiences as a child of tender age show deficiencies in the areas of empathic response, opportunities for emotional regulation, or distress tolerance. This is no excuse for bad behavior; never will be; however, it can point to transformation if the person is open and willing.

The narcissistic encapsulates his true self into a cocoon, hiding behind a fake self, in order to preserve the hope of aliveness and vitality if an empathic environment were ever to show up. If, in a context of safety for all, the narcissist is encouraged to lay back and to take a look at the precursors, triggers, and behaviors that he experiences as narcissistic insults and injuries causing him to break down or act out, then something starts to shift. They did not get enough empathy, did not get feedback on their own empathic responses (or lack thereof), got empathy but the responses were distorted or flat out crazy (causing the above-cited retreat into the emotional cocoon).

If the intervention gets off to a good start and the narcissist has a therapeutic response – that is, he feels better and stabilizes – then the work consists of trying to provide empathy, restoring understanding when empathy breaks down, restoring communication when communications break down, and restarting the development of positive personality traits such as empathy, humor, creativity that got lost in the narcissist’s deficient environment coming up.

The bottom line? Like most human beings, those with significant narcissistic tendencies and behaviors are susceptible of improvement. Sometimes there is no way to know for sure except to attempt the intervention in a context of safety and security. Unlike more serious forms of bad behavior exemplified by anti-social personality disorder, significant bullying, or boundary violating behaviors in which people get hurt, many narcissists are sufficiently in touch with their feelings and cravings for empathy that they will respond positively to an intervention in a context of safety and empathy.

Bibliography

Heinz Kohut, (1971). The Analysis of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

Lou Agosta and Alex Zonis (Illustrator), (2020). Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

Go to all A Rumor of Empathy podcast(s) by Lou Agosta on Audible by clicking here: [https://www.audible.com/pd/A-Rumor-of-Empathy-Podcast/B08K58LM19]

Okay, I have read enough. I want to get Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide, a light-hearted look at empathy, containing some two dozen illustrations by artist Alex Zonis and including the one minute empathy training plus numerous tips and techniques for taking your empathy to the next level: click here (https://tinyurl.com/y8mof57f)

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy and the True Believer

Empathy is going to do what it always reliably does: listen. So when empathy encounters the True Believer, empathy is going provide a gracious listening.

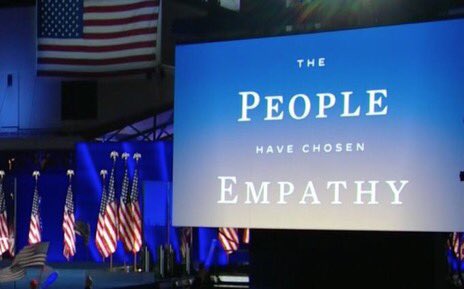

As empathic listeners, we start with an extreme case. We are listening to a narrative about how the space ship was supposed to arrive from Alpha Centauri to take the members of the group (or cult) to the Promised Land; but it did not arrive. As empathic listeners, we find ourselves listening to a narrative about how an election was stolen. However, so far, the recounts fail to surface the theft. We are listening to a narrative of how some racial or ethnic minority stabbed the nation of citizens in the back; but the supposed perpetrators are noticeably without power or influence consistent with such an action or result. We are listening to a discourse about how prayer makes us whole and faith fulfills our aspirations; but we experience prayers as unanswered (as if no one was listening) and faith as indistinguishable from the outcome of our own persistent efforts in a probabilistic universe of random events.

It does no good – it makes no difference – to take the belief system away from the True Believer. No marshaling of facts, no amount of logical argument, whether overwhelming or debatable, makes a difference. The True Believer is not engaging any alternative point of view. Why not?

The answer is direct: the belief system is what is holding the True Believer’s self, his or her personality, together. Take away the belief system and the personality falls apart. The person experiences emotional fragmentation, anxiety, and stress. This is why the True Believer becomes angry, starts to shout, escalates to rage in the face of countervailing arguments and facts. He experiences a narcissistic injury that threatens the coherence of his personality.

The work of empathy in the face of the True Believer consists in standing for an inquiry into one’s belief systems. If empathy is a belief system, then we inquire into that system too. Such a belief system – if we may tentatively call it that – opens out into a space of acceptance and tolerance. It is a belief system which is skeptical about belief systems. It is a belief system committed to inquiry. Key term: inquiry. Never stop questioning. Never stop listening.

Empathy creates a commitment to acceptance, toleration, and the ability to walk in the other person’s shoes. The True Believer is committed to a belief system, conformity, and marching together in step.

Since it would require an entire book to define The True Believer, I will just give a definition by example. It is a high probability you are dealing with a True Believer when, in the face of a setback to the Belief System (whether religion, political party, social movement, or spiritual cause) the adherent to the cause Doubles Down. Key term: double down.

For example, the end of the world does not arrive on the predicted date as predicted by the leader, the prophet, and the belief system. The space ship does not arrive from Alpha Centauri to take the True Believers to the promised land. You know the authentic True Believer when he experiences a set back to the movement, cause, and belief system to which he is devoted. Do the adherents of the belief system say: Oops, we might have overlooked something – some facts or alternative point of view; we might have made a miscalculation; or some of our assumptions require improvement? We might have made a mistake or two or overlooked a crucial detail? No! The True Believers double down.

What went wrong? Sometimes the fault is internal. The faith of the True Believer was not strong enough. We must confess our sins. Preferably, we must confess our failings in a public show trial and be martyred. However, preferably the fault is external. Outside agitators, the unwashed masses from a foreign land, a racial or ethnic minority stabbed us in the back.

Alternative facts, dangerous half-truths, and total nonsense are marshaled to account for the setback. “We was robbed!” “Betrayal!” The vote count shows we lost by five million votes; but those votes were invalid votes, stolen votes, non-existent votes, and, therefore, irrelevant. Anything except the simple fact, we screwed up (but how?) or our game plan did not survive the encounter with the real world situation at a given time and place. Thus, the definition by example of the True Believer.

You, dear reader, can see where this is going. How does empathy or an empathic person engage with the True Believer? If the True Believer takes a position that rules out an inquiry into the advantages and disadvantages, the benefits and draw backs, of one’s own or competing belief systems, then the conversation does not get going. How to get the conversation going?

Rarely is empathy irrelevant but there are some situations in which empathy is less (or more) useful than other situations. For example, if someone is throwing rocks, then understanding the rock throwing person is expressing his sense of grievance in a bad way is less useful than stopping them from throwing rocks.

Things such as self-defense, security, safety, basic well being are necessary aspects of the situation for empathy to make a difference. The True Believer is different from the bully, the psychopathic, the psychotic, or the fanatic, whether religious or political – but sometimes not that much different.

The guidance from empathy in the face of bullying, psychopathic manipulations, or rock throwing is to set limits. Likewise, with the True Believer. Key term: limit setting. Empathy is useful in deescalating aggression, hostility, violence, and other forms of acting out; but once the first rock flies through the air, the situation is no longer one about empathy. It is about reestablishing safety, security, and a space of acceptance and tolerance where empathy can actually make a difference. As noted, empathy is going to give the True Believer a good listening.

It is sometimes said that there is a little bit of larceny in all of us. That little bit of larceny is useful in empathizing with the bad boy or girl. That little bit of larceny is useful in figuring out what might have motivated a given individual’s antisocial behavior.

The same idea applies to empathizing with the True Believer. If you can relate to your own inner True Believer, then you might be able to engage with the True Believer’s in the community to understand what makes them tick.

The challenge is that in relating to your inner True Believer, you are not really relating to an individual, you are relating to a belief system, some of the principles of which may be useful and sensible, others less so.

The secret of empathic relating to the True Believer is not agreeing or disagreeing, undercutting or side-stepping, antidepressants or antipsychotics, the secret is the relationship the empath has to his own inner True Believer. If you can find an area in which you really are a True Believer, then it is likely you can relate to a True Believer in a conversation for possibility in which both individuals are left in integrity, whole and complete.

How shall I put it delicately? An authentic patriot can be willing to die for his [or her] country and yet not be a True Believer. But can he be willing to kill for his country without being a true believer? This is hard to finesse. When challenged, True Believers escalate in the direction of a fanaticism of hostility and aggression, even if they stop short of the death penalty.

I hasten to add that national defense is a valid function of the national armed forces, and I honor service men and women, first responders, and those committed to homeland security. Following orders to shoot the enemy on command of the commanding officer does not make one a True Believer. But it does make one a cog in a mechanism of defense, which in most cases requires a therapeutic recovery process to regain lost aspects of one’s humanity upon discharge from the armed forces.

Is the True Believer like the bully, the psychopath, or the perpetrator of domestic violence, for whom the more expanded empathy you give the person, the more ways the True Believer has to manipulate and abuse you? Some of the best parts of empathy – reduced stress, emotional regulation, self soothing – do not get deployed because empathy must put all its energy into setting limits to the boundary issues and violations.

The fall back position of empathy – which paradoxically ceases to be empathy – is to have compassion or even pity for the misguided soul who needs such a delusional system to feel or maintain a grip on reality. Absent successful boundary setting using empathy, the recommendation is to dial 911 and summon emergency services to restore order and tranquility (a desperate measure indeed, given that the police may arrive with guns out – how is that serving and protecting?).

I anticipate an objection at this point. The devil’s advocate says: But, Lou, are you not a True Believer in empathy? The answer is direct: No. I am committed to undertaking an inquiry into empathy. Empathy has strengths and weaknesses. It can misfire or it can succeed. It is susceptible of improvement in many situations. I hasten to add that I am also committed to using empathy to benefit people and organizations in the community. I am a shameless and unabashed promoter of the value of empathy. I will go to the matt on this one.

However, even if you do not believe in empathy, are persuaded that empathy is over-rated, or prefer rational compassion, I will still try my best to give you a good listening and to use empathy to make a positive difference in our relationship. No doubt more needs to be written about empathy and the True Believer. The politics of empathy is deep and complicated. There is a lot at stake. Literally.

This may indeed be a “love the sinner but hate the sin” moment. But such a moment is the positive part of empathic spirituality without which fanaticism causes spirituality to go off the rails and burn people at the stake. So if you find yourself or your neighbor gathering kindling for a bonfire, make sure it is to roast one’s own idols, pretensions, and vanities, not your neighbor.

Bibliography

Eric Hoffer. (1951). The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. New York: Harper Perennial.

(c) Lou Agosta PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Noted in passing: Arnold Goldberg, MD, Innovator in Self Psychology (1929-2020)

The passing of Arnold I. Goldberg, MD, on September 24, 2020 is a “for whom the bell tolls” moment. No doubt his family, students, friends, and colleagues feel the loss most acutely; however, the community is diminished, though in another sense irreversibly enriched by his contributions and innovations in expanding empathy.

Our loss is great, yet we breath easier thanks his lessons in empathy, which is oxygen to our souls.

Arnold I. Goldberg was an innovator in psychoanalysis and self psychology, a prolific author (really prolific!), an inspiring educator, and simply a wonderful human being.

My personal recollections are of Dr Goldberg inspiring my younger, graduate student self to pursue and complete a dissertation on empathy and interpretation at the

Arnold Goldberg, MD, enjoying Labor Day September 09, 2010 at his vacation home at the Indiana Dunes, illustration by artist Alex ZonisUniversity of Chicago Philosophy Department. I fondly recall introducing Arnold to one of my dissertation advisors, Paul Ricoeur, over a wine-enriched dinner at the middle eastern restaurant that used to be on Diversey Avenue (the Kasbah?). I was also lucky enough to take a year long case conference at Rush Medical that he taught to the psychiatric residents as part of the Committee on Research and Special Projects sponsored by the Chicago Institute for Psychoanalysis. Notwithstanding a multiyear gap during which our paths diverged, I have known him and his wife Connie (herself a Self Psychology power) since I was a twenty-something; and I still have in my possession a couple of his hand written letters to me regarding hermeneutics that I used to good purpose when “roasting” him at a retirement event at Rush Medical. What a privilege: I experienced Arnie’s deep listening, incisive and penetrating wit, the humor, the humanity, the remarkable learning and even-handedness in disagreement, and above all – his empathy.

I choose to republish this book review from June 23, 2013 precisely because its provocative title best encapsulates the validity of Goldberg’s contribution to psychoanalysis and self psychology while subtly and humorously “sending up” some of his less flexible colleagues. Arnie, thank you for being you!

Read the complete review in the International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology: click here: GoldbergAnalyticFailureReview2014

The power of Arnold Goldberg’s approach in The Analysis of Failure: An Analysis of Failed Cases in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis (Routledge) is twofold. First, if a practice or method cannot fail, then can it really succeed? If a practice such as psychoanalysis or dynamic therapy can fail and confront and integrate its failures, then it can also succeed and flourish.

Such is the point of Karl Popper’s approach to the philosophy of science in Conjectures and Refutations. For those who have not heard of hermeneutics, narrative, and deconstruction, and who are still suffering from physics envy, the natural science have advanced most dramatically by formulating and disproving hypotheses. Natural science is avowedly finite, fallible, and subject to revision, advancing most spectacularly within the paradigm of hypothesis and refutation by failing and picking itself up and pulling itself forward.

The Analysis of failure is inspired by this lesson without engaging in most of the messy details of the history of science. Second, for a discipline such as psychoanalysis (and psychodynamic therapy) that prides itself on the courageous exploration of self-deceptions, blind spots, self-defeating behavior, and the partially analyzed grandiosity of its practitioners (and patients), the well worn but apt saying “physician heal thyself” comes to mind.

The professional ambivalence about taking a dose of one’s own medicine upfront is a central focus not only in psychoanalysis (in its many forms) but in related area of psychiatry, psychopharmacology, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), social work, clinical psychology, and so on. Goldberg’s openness to alternative conceptions and frameworks along with his exceptional knowledge of and commitment to psychoanalysis (and self psychology) is an obvious strong point.

As a former colleague of the late Heinz Kohut, Goldberg studiously avoids (and indeed fights against) adopting the paranoid position with respect to failed analytic and psychotherapy cases – what’s wrong here? When a therapy case fails (the determination of which is a substantial part of the work) a series of blame-oriented questions arise: What’s wrong with the patient? What’s wrong with the therapist? What’s wrong with the treatment method(s)? What’s wrong!? And, yes, these questions must be engaged; but, Goldberg demonstrates, they must be put in perspective and engaged in the context of a broader question What is missing the presence of which would have made a difference? The answer will often, but not exclusively, turn in the direction of a Kohut-inspired interpretation of sustained empathy.

This leads to the part of Goldberg’s argument that is explicitly humorous. Having announced a case conference on failure and invited all levels of colleagues, Goldberg reports the casual laughter of many colleagues as they announced that they had no failed cases and so could not be helpful. “One person agreed to present but the following day he yelled across a long hall that he could not and quickly walked away (p. 41).

The list of excuses goes on and on, producing a humorous narrative that is definitely a defense against just how confronting the whole issue really is. Less humorous and more problematic is what happens when a case comes to grief and the candidate reportedly does exactly what the supervisor recommends. How one would know what is the “exact recommendation” is hard to determine, but relations of power loom large in such a triangular dynamic. Even Isaac Newton acknowledged that the “three body problem” of the (gravitational) relations between any three bodies is theoretically computable but practically intractable. The number of variables changing simultaneously is such that we are dealing with expert judgment rather than algorithmic results.

For my part I cannot help but think of the process for airline pilot reporting of errors in procedures, operations, and maintenance. Yes, pilots are part of a complex system and “pilot error” does occur – pulling back on the stick to get lift rather than pushing down – yet they are usually given more training and rarely blamed or faulted, absent illegal or blatantly unethical conduct (e.g., drinking on the job).

Goldberg calls for an ongoing case conference inquiring into failed cases, and thereby implicitly calls for taking our thinking to a new level of professional rigor, encompassing scientific objectivity that is consistent with talk therapy being a hermeneutic discipline. One might call it looking at the entire system, but not in the sense of family therapy –rather in the sense of the total professional-cultural-scientific milieu.

However, Goldberg’s approach differs decisively from a Check List Manifesto (a distinction not in Goldberg (he does not need it) but abroad in the land and by a celebrity MD, Atul Gawande) in that individual chemistry looms large between the therapist and the patient. In analysis or therapy, the number of unknown variables in fitting a prospective patient to a prospective treatment (whether analysis, therapy, psychoparm, CBT, etc.) is so large as to be nearly intractable. These are areas where we simply lack the super-shrink who has mastered the basics of all these methods and can make an objective, upfront call of what just might have the best odds of a favorable outcome without the usual trial and error. For the foreseeable future, mental health professionals can be expected to continue to “sell what they got.” If a person knows Talk Therapy, then that is most often what is initially recommended. If that does not work, try CBT or medication – and vice versa.

This reviewer does not agree that the crashes in the mental health area are usually not so spectacular – and they do make the papers in the form of suicides and inexplicable violence – though the track record is no where near the five-nines (one error in a million) that characterizes the airline industry. Goldberg’s subtext for mental health professionals is that we are still learning to live with uncertainty even as we organize case conference, postmortems, and the equivalent of crash investigations that strive to look objectively at outcomes without blame and without omniscient rescue fantasies in the service of healing and professional (“scientific”) development.

In some thirty cases that were reviewed by Goldberg, using the method of expert evaluation and feedback by the participants in the local case conference, the definition of failure included cases that never get off the ground; cases that are interrupted and so felt to be unfinished by the therapist or analyst; cases that suddenly go bad, characterized by a negative eruption whereas previously therapy was perceived to be going well; cases that go on-and-on without improvement; cases that disappoint whether due to the initial goal not being attained or being modified and not attained or endless pondering of what might have been.

Since this is not a “soft ball” review, one category of failure that is conceivable but missing from The Analysis of Failure is the example where treatment arguably left the person worse off (other than in terms of wasted time and money, which itself is not trivial). What about someone who did not experience impotence, writer’s block, or (say) hysterical sneezing until they tried psychoanalysis (psychotherapy)? What about compliance and placating behavior, reportedly a significant risk in the case of candidates for analytic training? What about regression in service of treatment that was initiated within the empathic context of the therapeutic alliance, but something happened and the regression got out of control and a breakdown or fragmentation occurred? Work was required to contain the fragmentation that was minimally successful, prior to an untimely termination that was a flight from fragmentation, a flight into health or a statement that in effect said “Let me otta here for my own good!” To his credit, Goldberg identifies “a patient who was getting worse off” (p. 162), but leaves the matter unconnected to regression mishandled or any other psychodynamic explanation. It is possible that such a scenario is already encompassed in the category of “cases that go bad,” at least implicitly, but in an otherwise through review of possibilities, this one was conspicuous by its absence.

The book itself is Goldberg’s answer to the question, given that failure occurs, what do we do about it? We inquire, define our terms, organize the rich clinical data, identify candidate variables, take the risk of making judgments about possible, probable, and nearly certain reasons, causes, and learn from our failures, pulling ourselves up by our boot straps in an operation that seems impossible until it succeeds. The role of lack of sustained empathy, counter-transference, rescue fantasies, disappointments, uncontrolled hopes or fears, partially analyzed grandiosity (on the part of the therapist), lack of knowledge of alternative approaches to therapy, are towards the top of a long (and growing) list of issues to be engaged in the classification of causes for failure.

The turning point of Goldberg’s argument occurs in his chapter on “How Does Analysis Fail”? This is an obvious allusion to Kohut’s celebrated work on How Does Analysis Cure? Once again, failure is a deeply ambiguous term, and the ironic edge is that in contrast to an analysis gone bad where the patient leaves in a huff with symptoms unresolved, a successful self psychology analysis proceeds step-by-step by tactical, nontraumatic failures of empathy that are interpreted and used to promote the development of self structure. The short answer is that analysis cures through stepwise, incremental, nontraumatic breakdowns – i.e. failures – of empathy, which are interpreted in the analytic context and result in the restarting of the building and firming of psychic structure of the self. In turn, these transformations of the self promote integration of the self resulting in enhanced character traits such as creativity, humor, and expanded empathy in the analysand.

The entertaining and even heartwarming reflections on Goldberg’s relationships with his teachers Max Gitelson and Charles Kligerman, betrayed (at least to this reader) a significant critique of the “old guard,” resolutely defended against the possibility of any failure, thanks to a position that avoided any risk – analysis is about improving self-understanding. According to this position, the reduction of suffering and symptoms relief is a “nice to have” but not essential component. Analysis is a rite of passage into an exclusive club, where you are just plain different than the untransformed masses.

Though Goldberg does not emphasize the debunking approach, the reduction to absurdity of the description of the old guard makes psychoanalysis sound a tad like the est training from the late 1970s. You just “get it” or you don’t – in which case here is your money back and now go be miserable and unenlightened (only analysis does not give you your money back). In both cases failure is not an option, though not in the sense initially intended by the slogan, namely, that risk is analyzed and mitigated through interpretation. Failure is not an option because it is excluded by definition from the system of variables at the onset, thus, also excluding many meaningful forms of success. In short, many things are missing including sustained empathy, which, in turn, becomes the target of the analysis of failure in the remainder of the book

The net result of the compelling chapters on Empathy and Failure, Rethinking Empathy, and Self Psychology and Failure, is to challenge the analyst and psychotherapist to deploy sustained empathy in the service of structural transformation. While I personally believe that agreement and disagreement are over-valued in terms of creating authentic understanding, the section on Empathy and Agreement raises a significant distinction between the two terms. It is insufficiently appreciated by many clinicians how agreement becomes a smoke screen – and defense against – basic inquiry and exposure to the other’s affects in all their messiness and ambivalence. It remains unclear how sustained empathy undercuts agreement (or disagreement).For example, Dr. E. wants his analyst to agree with him that it is okay to sleep with his patient(s). For the sake of discussion, the analyst mouths the form of words, “Okay, given your marriage, okay, I agree.” But Dr. E. then asserts that he can tell the analyst does not really mean it (an accurate observation). So why not raise the question what is agreement doing here other than disguising Dr. E.’s own unacknowledged commitment to “being righteous and justified”. There is nothing wrong with being righteous, everyone does it. However, is it workable?

The resistance has to be engaged and interpreted at some point in order to make a difference in treatment. Agreement (or disagreement) remains a conversation with the superego, even in the mode of denying there is amoral issue. It may stop a tad short of moral justification, but it is on the slippery slope to it. There are many cases along a spectrum of engagements but the really tough one is empathizing with behaviors that are ethically and legally suspect such as doctors sleeping with their patients and other relations of power where one individual uses his or her position to dominate the other as a mere means not an end in him- or herself. This is a high bar in the case of empathizing with the child molester or Nazi who have used a form of empathy (arguably a deviant one) to increase his domination of the victim. This remains a challenge to our empathy as well as to our commitment to treating a spectrum of behavior disorders (where Goldberg has made a life-long contribution) that are significantly upsetting to large parts of the mental healthcare market. Keeping in mind the scriptures and the sayings of Jesus(the rabbi), which Goldberg does not mention but arguably is the subtext, we are still challenged to love the sinner but hate the sin.

In a concluding rhetorical flourish, Goldberg claims that the book is a failure. The prospective reader – a very wide audience as I am any judge of the matter – may see the many complimentary remarks that properly disagree with this rhetoric printed on the back cover (which this review endorses and agrees). In a further ironic and richly semantic double reverse in the title of the final chapter, failure has a great future. This is especially so when failure is scaled down from a global narcissistic blind-spot on the psyche of the therapist (where failure remains a valid research commitment) to an expanded tactical approach in the form of “optimal frustration … disappointment being real, tolerable, and structure building” (p. 200).

The concluding message is an admirably nuanced clarion cry for further study rather than condemnation, finger pointing, or blame of some particular therapeutic modality such as Talk Therapy versus CBT. The concluding message is a sustained reflection on de-idealization, the difficult process of taking responsibility for the inevitability of one’s parents’ lack of omnipotence. Failure is part of the development process in analysis and psychotherapy, and, by implication (and taken up a level), the study of failure in broad terms will be part of the development of the profession going forward. The analyst and therapist must give up the rescue fantasy, give up being right and justified, give up misplaced ambition, but also give up guilt, self-blame, disappointment, and embrace an approach that interpretation of the pathogenic situation of early childhood in which traumatic deidealization of the parent occurred, becomes inherently transformative. It reactivates the process of structure-building internalization. Learning to live within one’s limitations invites a process of risk taking that sometimes results in failure, sometimes results in success, and always results in – redefining one’s limitations outwards towards an endless horizon of progress in satisfaction and meaning making. Our thanks to Arnold Goldberg both for the journey and the end result.

Chicago Tribune Obit, Sept 29, 2020: https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/chicagotribune/obituary.aspx?n=arnold-i-goldberg&pid=196869091

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

A Rumor of Empathy is now a podcast (series)

Got to Empathy Lessons on Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/1OvEwkDD9b3IH66erzehnM?si=MeQ6C1uTQDyYGuAUGbegBw ] [more episodes coming soon]

Go to all A Rumor of Empathy podcast(s) on Audible by clicking here: [https://www.audible.com/pd/A-Rumor-of-Empathy-Podcast/B08K58LM19]

A rumor of empathy (the podcast) hears of a report of an alleged example of empathy in the work, action, or conversation of a person or organization. I then reach out to the person and talk to them in detail about the work they are doing try to get the facts and confirm or disconfirm the validity of the rumor. Makes sense?

A Rumor of Empathy is committed to providing a gracious and generous listening, empathy, in conversation with its guests and listeners. Join the host in chasing

down and confirming or debunking an unsubstantiated report of empathy in the community and engaging in an on the air conversation in transforming human struggle and suffering into meaningful relationships, satisfying results and contribution to the community. When one is really listened to empathically and heard in one’s struggle and effort, then something shifts. Possibilities open up that were hidden in plain view. Action that makes a difference occurs so that empathy becomes less of a rumor and an expanded reality in your life and in the community. When all the philosophical arguments and psychological back-and-forth are over and done, in empathy, one is quite simply in the presence of another human being. Join Dr Lou for an empowering conversation in which empathy is made present.

Go to all A Rumor of Empathy podcast(s) on Audible by clicking here: [https://www.audible.com/pd/A-Rumor-of-Empathy-Podcast/B08K58LM19]

Empathy and humor – resistance to empathy?

Humor and empathy are closely related. We start with an example that includes both. Caution: Nothing escapes debunking, including empathy. My apologies in advance about any ads associated with the video.

Both empathy and humor create and expand community. Both empathy and humor cross the boundary between self and other. Both empathy and humor relieve stress and reduce tension.

However, empathy crosses the boundary between self and other with respect, recognition, care, finesse, artistry, affinity, delicacy, appreciation, and acknowledgement, whereas humor crosses the boundary between individuals with aggression, sexuality, or a testing of community standards.

If you have to explain the joke, it is not funny – nevertheless, here goes.

The community standard made the target of satire in the SNL skit is that people are supposed to be empathic. The husband claims he wants to understand social justice issues but when given a chance to improve his understanding – drinking the empathy drink by pitched by the voice over – he resists. He pushes back. He pretends to drink, but does not even take off the bottle cap. When pressured, he even jumps out the window rather than drink the drink.

The wife does not do much better. She resists expanding her empathy too, by pretending that, as a woman, she already has all the empathy needed. Perhaps, but perhaps not. People give lip service to empathy – and social justice – but do not want to do the hard word to create a community that is empathic and works for all.

The satire surfaces our resistance to empathy, our double standard, and our tendency to be fake about doing the tough work – including a fake empathy drink. If only it were so easy!

Therefore, be careful. Caution! The mechanism of humor presents sex or aggression in such a way that it creates tension by violating social standards, morals, or conventions. This occurs to a degree that causes stress in the listener just short of eliciting a counter-aggression against the teller of the story or joke. Then the “punch line” relieves the tension all at once in a laugh.

Another sample joke? This one is totally non controversial, so enables one to appreciate the structure of the joke.

A man is driving a truck in the back of which are a group of penguins. The man gets stopped for speeding by a police officer. Upon consideration, the officer says: “I will let you off with a warning this time, but be sure to take those penguins to the zoo.” The next day the same man is driving the same truck with the exact same penguins. Only this time, the penguins are wearing sunglasses. The same police officer pulls the driver over again and says: “I thought I told you to take those penguins to the zoo!” The man replies: “I did. Yesterday we went to the zoo. Today we are going to the beach!” Pause for laugh.

The point is that humor, among many things, is a way in which one speaks truth to power—and gets away with it. In this case, one disobeys the police officer. One is technically in the wrong, though vindicated. Penguins in sunglasses are funny. More specifically, the mechanism of the joke is the ambiguous meaning of “takes someone to the zoo.” One can go to the zoo as a visitor to look at the animals or one can be incarcerated there, as are the animals on display.

Instead of a breakdown in relating such as “you are under arrest!” the relationship is enhanced. The driver is following the officer’s guidance after all, granted the interpretation was ambiguous.

You get a good laugh—and a vicarious trip to the beach added to the bargain. Empathy is the foundation of community in a deep way, for without empathy we would be unable to relate to other people. Humor and jokes also create a community between the audience and storyteller as the tension is dispelled in the laughter (see also Ted Cohen on Joking Matters (1999)).

The story creates a kind of verbal optical illusion, a verbal ambiguity that gets expressed in laughter. In empathy perhaps one gets a vicarious hand shake, hug, “high five,” pat on the back, or tissue to dry a tear, expressing itself in recognition of our related humanity, while affirming and validating the self-other distinction.

Featured image of laughing carrousel horses (c) Alex Zonis

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD and the Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy and Architecture: On Foundations

Empathy is about relationships. Architecture is about building things that last. Building lasting relationships? A marriage made in heaven?

When you are building something – whether a bridge, house, or a relationship – the challenge is to get the fundamentals just right. The foundation is what connects the structure to the earth. This is the case especially with bridges that span vast chasms.

The architect building a structure knows that the structure has to go down to bedrock. You have to go down to what is stable and abides or the structure can be magnificent, beautiful, and elegant; but it will crack, lean over like the leaning Tower of Pisa, and then fall over due to design flaws. Or like the Tacoma Narrows bridge, it will start resonating in the wind and tear itself loos from its foundation and collapse. [Granted, the Leaning Tower was “fixed” by those ingenious Japanese engineers who hollowed out a space on the higher side enabling the Tower to “fall up.”]

Therefore, to explore the bedrock for the structure of empathy we have to ask what is bedrock in human relations? But wait. I thought the foundation of human relations was – empathy. The bedrock is empathy.

But what is the bedrock of the bedrock? On what is empathy itself founded? How do we get access to the foundation of the foundation? Isn’t the foundation just the foundation? Not exactly. Read on.

The way to get access to the question of what is the foundation of the foundation is to ask what can go wrong. Imagine empathy was a bicycle – it can get a flat tire, the handle bars can fall off, the chain can break, or the rim can get bent, and so on. A square wheel won’t roll. In each case, something is missing – wholeness. The bike as a bike is incomplete and, therefore, does not work.

Likewise with empathy. Empathy can break down. When we engage with the break downs, we get access to the foundation.

Empathy can break down as emotional contagion, conformity, projection, or get lost in translation. In each case, something is missing – wholeness.

The foundation of the foundation is integrity. The Roman Stoic politician and philosopher Cicero defined “insanity” (insanitas) as lack of wholeness, incompleteness, or being fragmented (see Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations a Roman “psychiatry”). Here “integrity” is not meant in the narrow ethical sense of right/wrong, but rather “integrity” in the sense of being authentic. In the case of empathy integrity means being present with the other person without anything else added or missing.

Therefore, the foundation of empathy is working on one’s own integrity and authenticity in being related. Without such a foundation, one is building on a mud pie.

You know how when things go wrong, the tendency is to find someone to blame and point the finger in someone’s direction? The word “responsibility” can hardly be uttered and our listening is “bad and wrong” and “who’s to blame,” you know? You did it! He did it! She did it! Now in the course of this work on empathy that finger has a tendency to change direction – and it points to oneself.

“I say I am committed to keeping my agreements but I am actually committed to not rocking boat” “I say I am committed to freedom of expression but I am in fact actually committed to being liked, being popular.” “I say that I am generous in my relationships but I am actually attached to holding onto grudges and grievances.” “I say that I am committed to being faithful in my relationship but the only reason I am faithful is that in fact I lack opportunity to betray my partner.” “I say I am honest but cut corners and cheat on my business expenses or taxes.” “I say that I am committed to telling the truth but I am actually committed to looking good.” You can provide examples of your own. This list goes on.

Therefore, clean up your own messes first. I have to work on myself – and you, dear reader, have to work on yourself – and we have to clean up our own acts prior to taking the empathy game to the street and coaching others.

The foundation is cleaning up one’s own integrity outages. Acknowledging the cost and impact and, where possible, making restitution and repair. The ultimate path to authenticity is cleaning up one’s inauthenticities.

Because a bridge falls down does not mean that bridge building is a failed science; because a tower leans over does not mean that the physics of building towers is in error. It means human beings on occasion misapply the practices of bridge building and tower making. Likewise with the practice of empathy. It’s the practice that counts.

Without consistent, enduring practice, the results you get will be a roll of the dice; and getting lucky is not a viable plan when anything important is at stake. That is the bad news and also the good news in expanding empathy in the individual and the community. It’s all about the practice.

Three recommendations: practice, practice, practice – and be sure to get a second opinion – a coach – to provide feedback on your practice (so the bridge doesn’t fall down!),

So, back to the architectural metaphor: a lot of site preparation is needed. The structure is multi-unit and multi-person. The site of empathy includes receptivity of the other’s feelings, understanding of the other as a possibility, talking a walk in the other’s shoes (the folk definition of empathy), and translating the other’s experience into one’s own and vice versa. Heating and cooling include emotional regulation and distress tolerance shows up as weather proofing and lightening rods.

From another point of view, empathy is not a standalone structure. It is a bridge connecting individuals and communities. It is a bridge over troubled waters on a stormy day and a source of satisfying relatedness on a sunny one.

Okay, I have read enough I want to get the book, Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide, a light-hearted look at empathy, containing some two dozen illustrations by artist Alex Zonis and including the one minute empathy training plus numerous tips and techniques for taking your empathy to the next level: click here (https://tinyurl.com/y8mof57f)

(c) Lou Agosta, PhD, and the Chicago Empathy Project

Empathy and Vulnerability

One of the misunderstandings of empathy is that “empathy means weakness.” Not so. Why not?

Empathy means being firm but flexible about boundaries. The most empathic people that I know are also the strongest and most assertive regarding respect for boundaries. Being empathic does not mean being a push over. You wouldn’t want to mess with them. Where such people show up, empathy lives—shame and bullying have no place. (For a working definition of empathy, see the note at the bottom of this post.)

Empathy thus solves the dilemma of how to deal with a bully without becoming a bully oneself. Bullies are notoriously causal about violating the boundaries of other people, because it is easier to cause pain than to feel pain. Bullies are taking their pain and working it out on other people. Bullies do not acknowledge their own vulnerabilities, and they work out their issues – I almost said “shxt” –on other people. Bullies are offloading their distress on other people. But what to do about it from an empathic perspective?

I am going to answer that question directly, but first take a short step back: Once the stones start flying back-and-forth, there is nothing to do but defend oneself or try to escape if outnumbered – retreat. If it is a school year brawl, hit ‘em back in self-defense if one is able. If the corporate boss is a bully, document and escalate – and update your resume just in case. If the bully is a politician, speak truth to power like Malcolm-X did: “You did not land on Plymouth Rock; Plymouth Rock landed on you” – use humor to bring down arrogance and privilege.

Once the stones start flying, the conversation is no longer about empathy or vulnerability. It is about who has the biggest cudgel or stone. Empathy did not work – empathy is in breakdown along with common courtesy and decency – call for backup! However, if things are still at the stage of name calling, remember what to my secular ears the ultimate empath of the spirit, Jesus of Nazareth, said and did. He was outnumbered with the woman “taken in adultery” confronting an angry mob of scribes, elders, and Pharisees, armed with large stones: “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone” (John 7:53 – 8:11). Nothing happened. No one dared be the first to assert his perfection. While the originality of this passage may be debated – did John really write it and who the heck is John, anyway – the pasage’s psychological power is beyond question.

In the face of loss of power, authority escalates to violence. Jesus dared to make himself vulnerable by aligning with the woman who had violated the community’s standards, which were so rigid that a case of infidelity threatened to below up the entire fabric of civilization. Otherwise, why would the authorities need to stone her to death? (And it really was all men who were about to do the stoning – so you can see there were many problems here!)

Always the astute practitioner of empathy, Jesus got inside their heads. He knew the authorities wanted to look good and claiming to be better than everyone else would make them look bad. Instead of shaming the woman Jesus turned the tables and put the authorities to shame. To get power over shame one has to allow oneself to be exposed and vulnerable to it. Be proud!

Thus, Brené Brown makes a parallel observation about vulnerability – she does research on vulnerability and shame – and asserts that it is a myth that “vulnerability is weakness.” Thus her project is to expand our appreciation of the power of vulnerability.

As Brené Brown uses the distinction “vulnerability,” she means living with uncertainty, living with risk, and living with emotional exposure. She understands vulnerability to mean letting go of “looking good” or fear of being ashamed. She means it to go in harm’s way emotionally or even physically and spiritually by having difficult conversations and taking actions about the things that make a difference – relationships, finances, careers, values, fairness, and so on. The inner game of vulnerability is different than the behavioral vulnerability that consists in leaving the password to your bank account on a yellow sticky pasted to your computer.

Brené Brown’s coaching is to expand vulnerability in the sense that I have my vulnerabilities; not my vulnerabilities have me. Her lesson “no courage without vulnerability” means that the courageous person goes forth into risk and danger in spite of being afraid. The person who imagines he is without fear is precisely the one who behaves in a foolhardy way, for example, Colonel Custer at the Little Bighorn, about to be wiped out, saying “We’ve got them now!” completely unaware of the risks he was taking. He did not have his vulnerability; his vulnerability had him – and did him in along with his regiment.

I hasten to add that empathy and vulnerability are different phenomena, not to be confused with one another. They are not either/or – the world needs more of each one – expanded empathy as well as the power conferred by expanded vulnerability.

You cannot do empathy alone. I get my empathy from the other individual. The other individual expands my empathy by giving me his; and I acknowledge the other individual’s humanity by giving him my empathy. The baby brings forth the parent’s empathy and is socialized by it – brought into the human community. The student brings forth the teacher’s empathy and is educated through it – brought into the educated community. The customer arouses the businessperson’s empathy and is served by it – brought into the community of the market. The list goes on.

Likewise, you cannot do vulnerability alone. The more armored up and defensive a person becomes, the less vulnerably, the less uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure the person incurs. However, without uncertainty, risk, or exposure, such essential results as innovation, productivity, courage, relatedness, satisfaction, and, yes, empathy, get lost.

Even though empathy and vulnerability are distinct phenomena, when they occasionally breakdown and fail, the component fragments are remarkably similar. Empathic receptivity breaks down as emotional contagion; likewise, in vulnerability a person is overwhelmed by the emotions of the moment.

Empathic understanding breaks down as conformity. Instead of relating to the other person as an authentic possibility, one conforms to the crowd and what “one does.” Likewise with vulnerability, risk is replaced with playing it safe, not rocking the boat, and remaining as invisible as possible.

Empathic interpretation breaks down as projection. Instead of taking a walk in the other person’s shoes to appreciate where they pinch the other person, one projects one’s own reactions and responses onto the other. Likewise with vulnerability, uncertainty is replaced with being right, making the other person wrong, and shutting down inquiry and innovation in the interest of not rocking the boat.

Empathic responsiveness breaks down in getting lost in translation. Instead of acknowledging the other person’s struggle as disclosing aspects of one’s shared humanity, one tries to “cap the rap,” get the last word in, and win the argument. Likewise with vulnerability, one talks about the other person instead of talking to them. Free speech is alive and well; but what has gone missing is listening. People are [mostly] speaking freely – no one is listening. It doesn’t work.

In each of the breakdowns of empathy, I do not have empathy – rather my break down in empathy has me. Instead of asking, what is wrong? Rather ask, what is missing? And, in this case, what is missing, the presence of which would make a difference, is a radical acceptance that empathy requires emotional exposure to the uncertainty and risk taking of related. That is precisely vulnerability.

When vulnerability is added to empathy the result is community. Since we are on a roll with our secular but empathic interpretation of spiritual readings, in the defining parable of community, empathy is what enables the Good Samaritan (Luke 10: 25–37) to be vulnerable to a vicarious experience of what the survivor of the assault and robbery is experiencing.

In contrast, the priest and Levi experience empathic distress – are armored up and defensive in the face of vulnerability – and have to cross the road. The Samaritan’s empathy tells him what the survivor is experiencing; and it is the Samaritan’s vulnerability and ethics that tell him what to do about it. The two are distinct. Yet empathy expands the boundary of who is one’s neighbor to be more-and-more inclusive, extending especially to those whose humanity has been put at risk by the vicissitudes of vulnerability. Be inclusive.

Note: the short definition of empathy is that it is a multi-phase way of relating to people individually and in community with receptivity to the other’s affects, understanding of the other as an authentic possibility, an appreciation of the other’s perspective, and responsiveness in acknowledgement of the other’s humanity in the other’s communication.

Bibliography

Brené Brown. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. New York: Avery, a Division of Random House Penguin.

Lou Agosta. (2010). Empathy in the Context of Philosophy. London: PalgraveMacmillan.

_________. (2014). A Rumor of Empathy: Rewriting Empathy in the Context of Philosophy. New York: Palgrave Pivot.

________. (2015). A Rumor of Empathy: Resistance, Narrative, and Recovery in Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy. London: Routledge.

_________. (2018). Top Seven Lessons on Empathy For Leadership (webcast): Chicago: 2018: https://youtu.be/GrgDWDt4uqg

________. (2018). Empathy Lessons. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

_______. (2018). A Critical Review of a Philosophy of Empathy. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

Lou Agosta and Alex Zonis (Illustrator). (2020). Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide. Chicago: Two Pears Press.

For further details and additional tips and techniques see Lou’s light-hearted look at the topic, Empathy: A Lazy Person’s Guide or one of his peer-reviewed publications see: Lou Agosta’s publications: click here (https://tinyurl.com/y8mof57f)

© Lou Agosta, PhD and The Chicago Empathy Project

The trouble with the trouble with empathy (this is not a typo)

Empathy flourishes in a space of acceptance and tolerance. But acceptance and tolerance have their dark side, too. People can be intolerant and unaccepting. Be accepting of what? Be accepting of intolerance? Be tolerant of intolerance? Yes, be tolerant, but set limits. But how to do that given that we may still have free speech in the USA, but many people have just stopped listening.

“The Trouble With Empathy” is an article by Molly Worthen published in The New York Times on September 04, 2020. The author gets many things just right in an impressive engagement with the complexities of empathy, but in other areas, including the citations of certain academics, I have an alternative point of view. Hence, the trouble with the trouble with empathy is not a typo. The reply is summarized in the diagram (note that it is labeled “Figure 2,” but it is the only diagram – page down, please). For those interested in more detail, read on.

Babies are not born knowing the names of the color spectrum. Children are taught these names and how to use them in (pre)Kindergarten; likewise, with the names of the emotions such as sadness, fear, anger, and high spirits. However, there is a lot more to empathy than naming one’s feelings and getting in touch with our mammalian ability to resonate with one another in empathic receptivity and understanding.

As an adult, the fact that you failed to be empathic does not mean that your commitment to empathy is any less strong; just that you did not succeed this time; and you need to keep trying. Stay the course. It takes practice. The practice is precisely the empathy training.